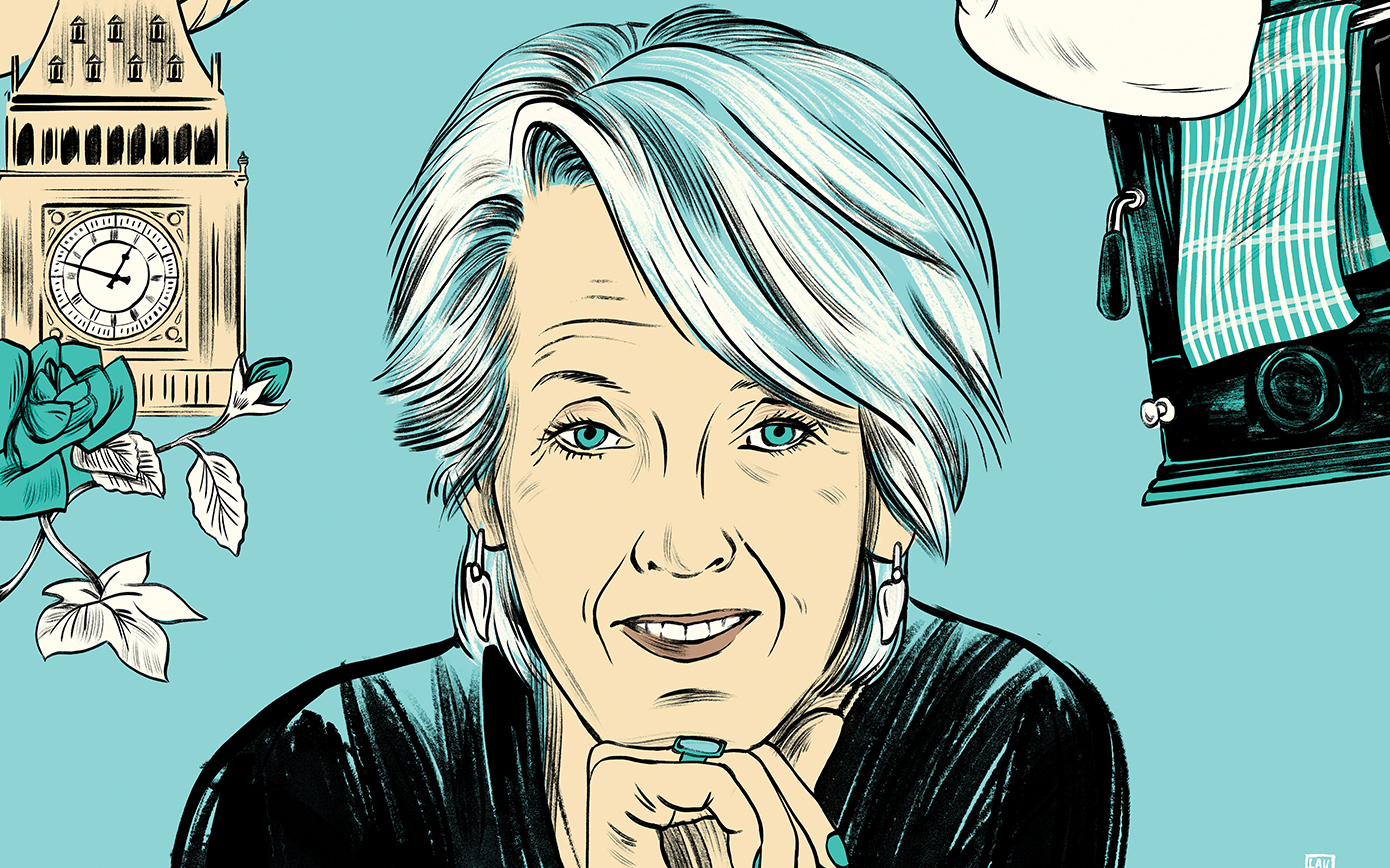

A feisty Joanna Trollope talks about self-sabotaging female friendships and how every novel has its own agenda

“There is a special place in hell for women who don’t support each other.” The last person you would expect to deliver such an infernal admonition is the fragrant chronicler of England’s manners and mores, novelist Joanna Trollope.

Everything about her: her voice, her appearance, her work, has always projected a delicate sensibility. Her mind, I was to learn, is made of doughtier stuff. We are barely two minutes into conversation when she paraphrases former Secretary of State Madeleine Albright’s war cry for Hillary Clinton.

Why am I surprised? Any of the characters in her latest novel might have said it: the dynamic being the conflicting pulls of female solidarity. City of Friends charts four women in their mid-forties, in a motley representation of modern relationships: married mother, single mother, gay. The common thread is they all work in the financial sector.

There’s very little sex in it, I remark, wondering if she had uncovered, in her observant way, a new truth; the parking of sex by women in the prime of working life. She is quite stern. “Sex didn’t occur to me when I was writing this. It’s a novel about work. I wanted to put work back into the centre of women’s lives. There are masses of novels about sex out there. Women are always identified with sex and romantic love.”

Had I grown complacent in the comfort zones of traditional Trollopeland – love, pain and the whole damn thing? “This one is about the intense satisfaction of work,” she says and there’s no doubting which satisfaction she rates highest.

“The choice of the financial sector is deliberate. I spent a long time in Canary Wharf researching. It’s a traditional bastion of the male, a bubble.” If this sounds sterile, relax. It meets my personal criterion – a good read should be like bingeing on a good box set – because Trollope is all about relationships. Besides, it contains some very subversive ideas around motherhood and work, that complicated tangle that feminism has still failed to unravel.

She stoutly defends Margaret Thatcher from accusations that she deserved a place in the hotspot. “There were no women for her to hire, she had to choose a man.” She has graver reservations on England’s other female Prime Minister. “Theresa May and I share a background. We are both Grammar school girls.” And they both grew up in rural rectories, but the similarities end there. Trollope, a firm Remainer, no longer has “the same admiration for May that I had when she became Prime Minister.” This could spell trouble for May, because one thing Joanna Trollope has, is a feel for is the pulse of Middle England. Those tropes used by lazy reviewers – middle class and middle brow, as though these qualities did not encompass solid virtues – sound hollow now that it’s clear it was ignorance of the rhythms of middle England that caused Brexit.

“What I want to promulgate is women standing together.”

Besides, childhood in the rectory was no cradle of comfort. Born during the war, she is firmly of the “mustn’t grumble,” generation. “I didn’t see my father until I was four. It was a terrible time. Men came back to a cold, tired, hungry country. It was worse than the war.” Women who had been welcomed in the workforce were expected to go back to the kitchen. “The rationing didn’t stop for years. That kind of austerity defined my generation. We still eat the leftovers.”

She lives alone in London now, but this is no leftover life. Between the rectory and her writerly eyrie, clearly glimpsed through her many novels, is a rich life. Two marriages, two divorces, (one caused “a mini breakdown”) two daughters, two stepsons and lots of grandchildren. “In my youth, you didn’t go to bed with someone without marrying them. Society was pleased with you for being pregnant. There was a terrible stigma if you had a baby out of wedlock. Even a stigma around adoption. For all its faults, society is much kinder nowadays.”

She now belongs in the great English tradition of the edifying novelist. Like Catherine Cookson, her novels have a purpose; to start a conversation. “If I was writing City of Friends 28 years ago, the conversation would probably have been about same sex relationships. For most of my life, homosexuality was illegal, lonely and distorted.” Twenty-eight years ago, A Village Affair, in more classic storytelling form, tells of a lesbian relationship which rocks a community. “It was stacked on the gay and lesbian sections in bookshops. It was a very daring thing to do. I regard all my novels as equally subversive.”

So what conversation does she want to start now? “Women and work and motherhood. I don’t see many novels about that.” Her central insight, through a character “who loves her children but adores her work” is that a women in a top job is drawing on skills that are uniquely maternal. “She has a very maternal effect at work.” She is concerned that the sabotaging of women in the digital age is mostly done by other women. “What I want to promulgate is women standing together.”

It is noticeable that Trollope no longer self-deprecates with remarks like “nobody reads me for the perfect sentence”, and I detect one delicious literary dig. “It’s all very well writing about the death of Anne Boleyn, but that’s all in the past,” (let nobody cry Wolf Hall). “I record the here and now. I take the eternal truths about human nature and filter them through modern routines.”

She’s bursting with ideas for more novels – childlessness may be next. She doesn’t dismiss early feminist claims. “It may be possible, on your deathbed, to look back and think you had it all.” If anyone can …

Illustration by Lauren O’Neill

LOVETHEGLOSS.IE?

Sign up to our MAILING LIST now for a roundup of the latest fashion, beauty, interiors and entertaining news from THE GLOSS MAGAZINE’s daily dispatches.