Although we are familiar with the work of Sir William Orpen from visits to the National Gallery, we know little of the artist’s complicated love life, which entailed a wife, a long-term mistress and a very young girlfriend whose portrait almost cost him his reputation. In Patricia O’Reilly’s new book, all is revealed…

Major William Orpen arrived at the Somme in April 1917, complete with a Rolls-Royce and a driver, an aide, a batman and a generous supply of Dewar’s whisky. His brief, as an official British war artist, was to paint images of the war. A sociable Irishman, he was one of the most successful society painters of the era. He had a penchant for jokes, self-portraits with gnarled features and frequently referred to himself in the third person as “little Orps”. Orpen (1878-1931) had grown up in a house called Oriel, in Stillorgan, in south county Dublin, the youngest of six children. His brothers were educated at St Columba’s College in Rathfarnham but his education was hit and miss as he showed artistic talent from an early age, which was nurtured by his mother.

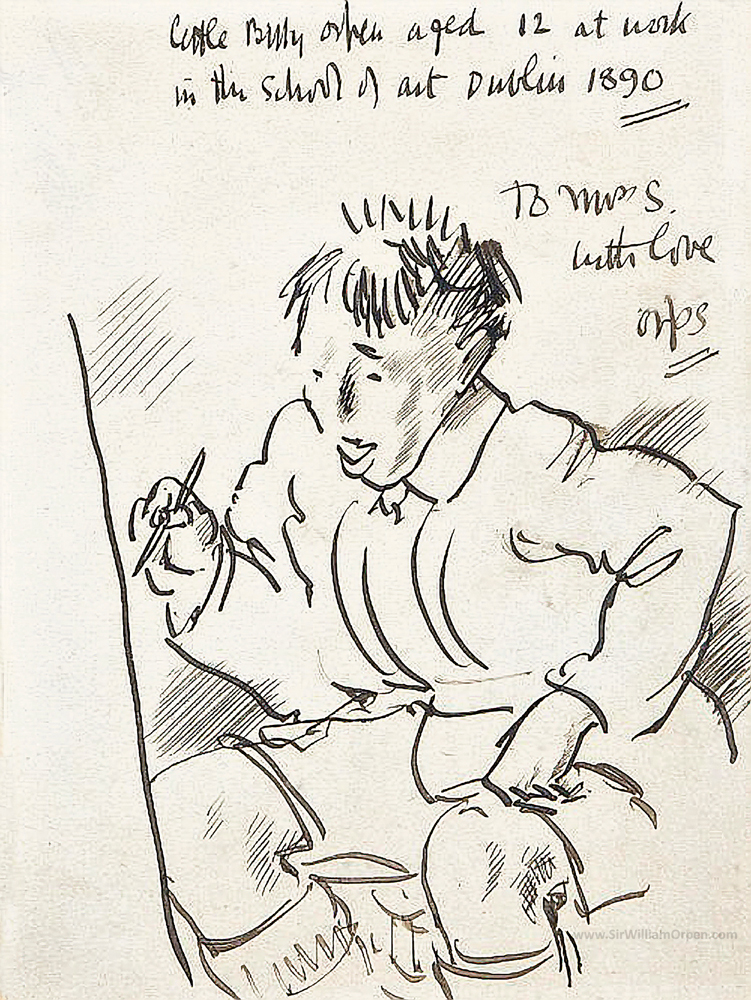

The family were ambitious, sporty and artistic. His father Arthur Orpen ran a successful legal practice and painted watercolours; his mother (Annie née Caulfeild, related to the Bishop of Nassau, Lady Gregory and Hugh Lane) was a competent watercolourist and a leading light in the burgeoning arts and crafts movement. William was accepted at the Dublin Metropolitan School of Art aged twelve and won every major prize there, plus the British Isles gold medal for life drawing, before leaving to study at the Slade School of Art in London. He was one of the most popular of the Edwardian artists, his work likened to that of John Singer Sargent, commanding fees of £200 for a portrait. He married in 1901 and set up home in South Bolton Gardens, the stylish end of Chelsea.

A self-portrait sketch of “Billy” Orpen, aged twelve.

His wife, Grace Knewstub, was the daughter of a well-respected artist. William’s mother recognised that she’d make a good wife as she’d understand the rigours of the artistic life; his father thought William could marry better, but changed his tune when Grace nursed his wife during her final illness and remained in Dublin to ensure his comfort. While living in Chelsea, during the summers Orpen arranged to teach at the Dublin Met, giving him the opportunity to return to Ireland and see his family and friends. Initially, Orpen treated his war posting as a bit of a Boy’s Own-style adventure. But reality soon struck. Nothing in his privileged life had prepared him for what he saw as the barbarism and madness of war. He was appalled at the fighting conditions of the Tommies who, half-starved, dodged bullets as they crawled through rat-infested, sodden trenches. At first, he had difficulty capturing on canvas what he referred to as “the essence of war”.

Ready to Start by William Orpen.

But after painting Ready to Start, a self-portrait, in his hotel room in Amiens, he got into his stride. From then on his output was prolific. Major AN Lee’s job was to censor the work of the artists at the front before forwarding it to London. His relationship with Orpen was spiky. Orpen was used to working at his own pace; Lee looked to manage the artists under his control. Delicate from childhood, Orpen was frequently laid low with colds and fevers but it was a bout of pneumonia coupled with septicaemia that landed him in hospital where he met Yvonne Aupicq and was smitten. He was in his early 40s and she was barely 20. She was a natural beauty who never wore make-up or jewellery. Aupicq grew up in Lille. Her mother was accidentally shot during the early days of the First World War and her father, an administrator, played a leading role in keeping Lille relatively calm during the German occupation of the city. Aupicq became a Voluntary Aid Detachment (VAD) nurse based at the hospital in Amiens where she met Orpen. Far from handsome and a mere five foot, two inches in height, from boyhood Orpen was attracted to women of all ages, and they to him. He had left behind in London his wife, Grace, and three daughters, as well as Evelyn St George, his long-term mistress and their daughter.

Yvonne Aupicq in The Refugee.

Of necessity, his affair with Aupicq had to be kept secret, but he couldn’t resist painting her. He included a portrait titled The Spy, in his next batch of paintings for assessment. Unsurprisingly, Lee asked for the source of the painting, pointing out that the War Office was sensitive about the subject of woman spies since the unfavourable publicity surrounding the firing squad deaths of Mata Hari and Edith Cavell. Rumour has it that Orpen, pleased at the idea of “getting one over on Lee”, spun an elaborate tale about being driven to an unidentified prison in an unknown suburb of Paris where he was taken to the cell of an unnamed young girl, the spy, who, he said, was reciting the rosary. Her one request was to die wearing her own clothes. It was granted and the following morning she faced the firing squad wearing her chinchilla coat and a pair of satin slippers. Refusing to be blindfolded or to have her wrists tied, as the shots were about to ring out, she dropped the coat and stood naked before the firing squad. Orpen assured Lee that he knew nothing more; he had a well-deserved reputation for being sparing of information and a reluctance to explain his art. But wondering if he had been too impetuous, he painted another portrait of Aupicq, this time wearing a modest dark blouse and blue jacket. He titled that The Refugee and, reputedly, felt the better for having it in reserve.

Yvonne Aupicq with Charles Grover-Williams.

Orpen had friends in high places, and it’s likely that Lee, perhaps against his better judgement, included The Spy in the paintings and drawings going to London. Some weeks later, William was summoned to the War Office to give an account of the painting. He never revealed what took place behind the closed doors of Whitehall. There were rumours that he might be recalled from France or even face court martial, but neither happened. His diary entry about the meeting was succinct: “I was in black disgrace.” However, his misdemeanours didn’t prevent his work being acknowledged. In the King’s 1918 Birthday Honours list he was made a Knight Commander of the Order of the British Empire, and Grace became Lady Orpen. An exhibition of his paintings, “War”, opened in The Agnew Galleries in May 1918. The reviews were mixed, The Times bemoaning: “His work adds nothing to our knowledge of war”, while the Daily Telegraph wrote that the paintings “vibrated through our hearts”. The exhibition was the talk of London with The Spy drawing a lot of interest.

Versions of the story of the spy did the rounds of dinner parties and it was rumoured that Lord Beaverbrook, the Canadian-British newspaper publisher and backstage politician, had acquired it. Interest in the paintings faded as the war ended. Prime Minister, David Lloyd George commissioned Orpen to “paint the peace”. He moved to Paris with Aupicq, taking up residence at the Hotel Majestic, studio space in the Hotel Astoria and rooms in a nearby apartment block for his newly appointed driver, Charles Grover-Williams, the son of an English horse breeder, who was born in Monaco, educated in the UK and lived for motor cars.

In Paris, Orpen was unwell, feverish, stressed and drinking too much. Now the war had ended, he was restless, unsure of his role in life and where he fitted in. He did not envisage a long-term future with Aupicq. Before returning to London, he settled a generous sum of money on her and left her the Rolls-Royce. (Orpen also made a financial settlement to Grace and she became legally responsible for their three daughters.)

Until he died in 1931, he divided his time between London where he stayed at The Savile Club, and Paris, where he had retained a studio. Having served in the British Army, he did not feel he could return to Ireland.

In 1929, Aupicq married Charles Grover-Williams, but she and Orpen remained in contact, meeting on occasion in Paris and Dieppe until his death in 1931 from alcohol-related illnesses. Charles worked for Bugatti Automobiles, racing on the Paris circuits and winning the Monaco Grand Prix. The pair belonged to the stylish Anglo-French set in Paris. During the Second World War, they were part of the Resistance, Grover-Williams code-named “Sebastian” and Aupicq working as a courier. Grover-Williams was captured, tortured and shot. Aupicq was arrested and imprisoned for a time at Fresnes prison in Paris and then released. After the war, she settled in Normandy where she ran dog kennels, even judging at Crufts. She never discussed Orpen or spoke of her relationship with him. She died in 1973.

Orpen at War, by Patricia O’Reilly, is published by The Liffey Press; www.theliffeypress.com