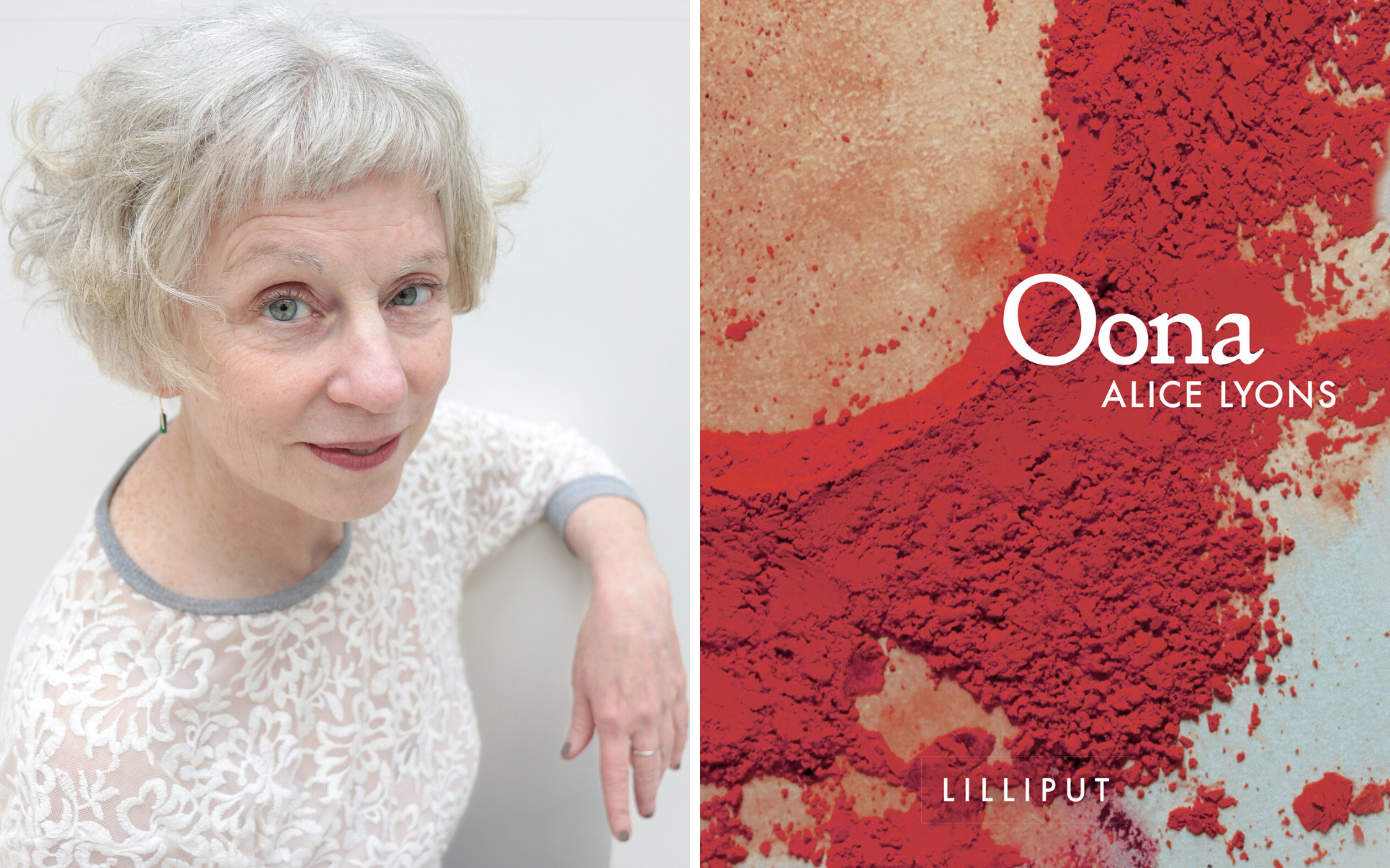

Alice Lyons is a poet and novelist with a great love for visual art forms. Born to an Irish-American family in Paterson, New Jersey, she has lived in the west of Ireland for over twenty years. She worked at Maine College of Art in Portland before leaving to start a new life in Co Roscommon in 1998.

Lyons often works with artists and film-makers on interdisciplinary and public art projects. She has co-directed poetry films with animator/artist Orla Mc Hardy, including their award-winning The Polish Language (2009). Her print poetry collections include Staircase Poems (The Dock, 2006) and The Breadbasket of Europe (Veer Books, 2016).

Lyons has degrees in European history, sociolinguistics, and fine art from Connecticut College, the University of Pennsylvania, and Boston University, as well as a PhD from the Seamus Heaney Centre for Poetry at Queen’s University, Belfast. She has received the Patrick Kavanagh Award for Poetry, a Radcliffe Fellowship in Poetry at Harvard University and the Ireland Chair of Poetry Bursary. She was announced as the inaugural poet-in-residence with the Yeats Society, Sligo in 2018.

Lyons’ first novel, Oona, is a resplendent creation unlike anything you’re likely to encounter. First of all, the author has managed to write almost the entire volume without using the letter O. That in itself is a triumph. When Oona’s mother passes away, her own voice is lost. What unfolds is a coming-of-age story about a young artist navigating loss, sadness and its physical and emotional manifestations. All of this amid the backdrop of Lyons’ hometown of Paterson and aspects of her own trajectory, as the character later experiences Ireland during the boom years. Over 99 short chapters, vignettes and slices of poetry, Lyons hypnotises us with her punctilious words. The book has already garnered covetable praise from some of Irish literature’s key players, including Susan Tomaselli, who said – “With echoes of Lydia Davis, Beckett, Eimear McBride and Max Porter, Oona is a nuanced narrativisation of the dislocation, disruption and stasis of grief, a treatise on silence, a drift on desire and sexual awakening.”

Alice Lyons lives in Sligo, where she lectures in creative writing at the Institute of Technology. She is currently working on her next book.

Oona (€15.00) is published by Lilliput Press and available from all good bookshops.

Photograph by Anna Leask

On home

I live in a 1940s cottage at the edge of a 1970s housing estate in Sligo town. Birch trees, barberry, cypress, and laurel hedging surround my place, so I’m hidden in plain sight. It’s ideal. My introvert loves the privacy and my extrovert is happy that people are nearby. From my study window at the back of the house, I watch the changing “catwalk” of the neighbourhood strays. Every day there’s a parade of furry outfits – pure white, stripes, spots, patches, and black never goes out of fashion. I’m courting one or two cats to be mine, urged on by my daughter who is now away at college.

My favourite café to meet friends or go solo is Heart’s Desire on the edge of Stephen Street carpark. Owner/barista Tony Conway is an artist of the espresso machine. The coffee beans are roasted locally, and Tony’s cortados are perfection.

On roots

The opening credits of The Sopranos is where I’m from: northern New Jersey, right outside of New York City. My mother was the daughter of a girl from Roscommon who was a maid in the homes of wealthy New Yorkers and, man, she knew how to clean. Murphy’s Oil Soap, Pledge furniture polish, Palmolive dish liquid – these are the scents of my childhood home. Childhood also smelled of veal piccata with lemon and capers, Italian roast espresso beans, and the garlicky tomato “gravy” that was ladled over ravioli in the Italian restaurants that we frequented.

On early reading

My parents weren’t educated beyond secondary school, but they were avid readers. My mother worked in the school libraries in our area, so I had a direct connection to the dealer, so to speak. On Friday afternoons, she’d lug home a stack of books for me to devour over the weekend. Harriet the Spy; Pippi Longstocking; Watership Down; The Wind in the Willows; anything Tolkien or C. S. Lewis; Nancy Drew mysteries. I still have a few of the books that she bought for me: Journeys, a collection of prose by children collected by Richard Lewis – a marvel to read actual children’s writing in a real book. And a biography of Mary Cassatt, the American impressionist painter who lived in Paris, someone I fantasized about being. My mother was very affirming of me and my burgeoning curiosities and her death from cancer when I was 14 was shattering.

On bloodlines

My maternal grandmother, Jane Higgins, was born near Ballaghadereen and my grandfather Christy Scott was from Cork city – his family ran a pawn shop on Pope’s Quay in the late 19th century as far as I know. It is sad that there are no photos of my mother’s parents. They are ghosts. My father’s people, the Lyonses and Quigleys, were Famine era emigrants. My paternal grandfather was a cop and grandma ran a bar, so I’m the stereotype Irish-American supplied by Central Casting. The Lyonses were from Munster, that much we know, and though I never met them, we have pictures of my father’s parents. They are more real to me. That’s the problem with being the youngest daughter of the youngest daughter – the grandparents were all but gone by the time I came along.

On Ireland

I don’t know what would have become of me if my mother hadn’t come to Ireland with me in tow when I was eight to search for her mother’s sister. It exploded my (limited, American) worldview and has everything to do with who I am today. Growing up where I did, it seemed everyone was hell-bent on ditching their ethnic identities to blend in to an overall whiteness. The suburbs felt place-less and culture-less except for an obsession with accruing wealth. I came to Dublin for a college semester and when I returned to the US, I wrote my first poems all about being here. My mother pointed me back where we came from, and as soon as I could get here, I moved. I had the sense that my material was in Ireland and Europe more generally.

I began to write without using the letter O. It did something strange: it drew me closer into the language.

On creating

Some of the stuff on my desk is mentioned in Oona. The hourglass is a gift from a dear friend in Oslo, and when time is tight, I make myself sit at the desk for two overturns of it: an hour. There’s a stack of pigments used for painting frescoes, gorgeous stuff. The blue whale drawing whispers “dive deep.” There’s my mother’s pastry blender, now acting as a sculpture. In a Muji acrylic block frame is a postcard Seamus Heaney sent out of the blue to say he was moved by The Polish Language, a poetry film I wrote and co-directed with artist Orla Mc Hardy. It’s an understatement to say I was gratified to know Heaney liked it, but even more was that he took the time to write; he was in the literary stratosphere but always kept his feet on the ground. It’s a talisman to generosity of spirit.

On independent bookshops

I play the field with bookshops. I love BookMart on Bridge Street, a used bookshop with a part DIY, part Dada sensibility. They host anarchic music gigs and open mic readings – a vital, non-corporate gem in Sligo’s cultural necklace. I also patronise the friendly Liber, our indie bookshop on O’Connell Street and the trusty Sligo Central Library on The Mall. I measure the vitality of a big city bookshop by the depth of its poetry section and the array of lit mags and journals they stock: Books Upstairs in Dublin scores high on both counts and the staff are so lovely.

On her “To Be Read” pile

The Sympathizer by Viet Thanh Nguyen is there because my sister said I’d like it, and my sister is always correct. Women Talking by Miriam Toews – her earlier novel, All My Puny Sorrows is astonishingly funny and terribly sad and feels so close to real life. I want to read all her books. Escape from the Anthill by Hubert Butler a brilliant essayist on Ireland and Europe and the reason my wonderful publishers, the Lilliput Press, started up. Brönte Wilde, an early novel by poet Fanny Howe, which I’ve read twice and am going for a third. So ahead of her time. I’m gearing up to read Undoing the Demos by political scientist Wendy Brown on how we are all being made into homo oeconomicus, bits of capital, and undoing the social contracts of democracy in the process.

On escape

I escape into the sea for a swim a few times a week in winter and daily in summer. A total reset of the operating system. As much as my schedule allows, I join a group of fearless women who weekly take off into the wilds of Sligo to hike, dip in a lake or the sea, brew coffee in a dune or a high bog. The beauty of this place has to be experienced or what’s the point?

When time and funds allow, I escape to Poland, a place I’ve travelled to for 30 years. Heaven is to open a (paper, crinkly) map with my Polish friends and plan our next road trip. To travel in Poland, rural and urban, is to encounter old wooden churches, vodka, vehemence about literature, storks, vehemence about history, stewed fruits plied by hardy grannies, and a language I’ve been trying to speak for 30 years.

On Oona

Oona grew out of a desire to write about a person who has been so knocked off centre by loss that she cannot really hear her inner voice. She feels silent to herself, and she struggles to break out of that bubble of detachment, or “dissociation” as it’s called. I wanted to write the body and its messy confusions, to move beyond writing as mere thinking. I started the book in 2015 just before I was awarded a year as a Radcliffe Fellow at Harvard. There, I had no duties other than to write, so I dug into the work – a total luxury. I began to write without using the letter O. It did something strange: it drew me closer into the language. It was like, I don’t know, maybe doing fine embroidery. It slowed me down and made the language a substance to mould and shape. It was both very difficult and very exciting.

On what’s next

My next book is bubbling away on the back burner; all I know is I need to go to Kraków and dig in an archive of a woman who took thousands of photographs of Polish people in their homes during the 1970s and 80s. I hope to go this summer.

Also, I’ve just enrolled in beginner lessons with a jazz drummer. I want to play like Bernard Purdie before my life is over. Wish me luck. Actually, wish my teacher luck.

LOVETHEGLOSS.IE?

Sign up to our MAILING LIST now for a roundup of the latest fashion, beauty, interiors and entertaining news from THE GLOSS MAGAZINE’s daily dispatches.