This landmark exhibition at Dublin Castle examines the role of former vicereines in Ireland. Not only does it shed light on their lifestyles but provides an opportunity to see artworks by Thomas Gainsborough, John Singer Sargent and Sir John Lavery, not normally on public display. Curator Dr Myles Campbell explains the legacies of these forgotten women from supporting Irish fashion to establishing hospitals …

Did the vicereines define their own roles much like diplomatic wives do today?

In many ways, the vicereine’s role was similar to that of a modern-day royal consort, but with less official definition, guidance and resources. This really comes across in a letter written by Elizabeth, Countess of Hardwicke just a few days after her arrival in Dublin as vicereine, in the summer of 1801. Almost immediately, she recognised the ambiguous and subordinate nature of her position compared to that of a royal consort. “He represents the King”, she wrote of her husband, “but it would appear that I do not represent the Queen, as I am not worthy to sit on his left hand, but have a horrible dirty arm chair in a side gallery…” I think the metaphor of the side gallery is a powerful one – these women occupied an elevated and extremely prominent position in Irish life, yet they operated at a remove. For this reason, I think their major achievements in the fields of charity, the arts and healthcare, which often did so much to better the lives of the disadvantaged in Ireland, are all the more remarkable and inspiring.

Many were activists – what beneficial initiatives did these vicereines initiate during their tenure in Ireland?

The establishment of hospitals, the relief of poverty and the promotion of Irish fashions and textiles were among their main contributions to Irish life over the centuries. The 19th century, in particular, was a period of intensive activity during which the vicereines developed increasingly sustainable forms of support aimed at helping Irish artisans and workers to help themselves. An early example is the work of Elizabeth, Countess of Hardwicke, who wrote of her shock at the “appearance of sickness and depression” among the people of Dublin. In 1805, she founded the Dublin Charitable Repository, an early and important retail outlet for the sale of Irish textiles. Having woven their wares at home, struggling women could then sell them anonymously at the Repository and earn up to £300 a year – the equivalent of more than €23,000 in today’s money. At a time of limited employment opportunities for women, this income made a real difference, giving disadvantaged women a degree of financial independence.

As vicereine in the 1830s, Maria, Marchioness of Normanby expressed a strong view that the Irish people had, in her words, “never received justice from any English sovereign before”. I think this comment shows her remarkable insight into some of the deficiencies and inequalities of British rule in Ireland. By stretching out the hand of friendship to Daniel O’Connell, insisting on strict impartiality when visiting and entertaining people of all faiths across Ireland, and working tirelessly to develop and modernise the Irish textile industry, Maria tried hard to address these shortcomings. Conscious of a lack of official support for Irish weaving, she personally persuaded the young Queen Victoria to grant the first royal warrants for Irish fabrics, to commission large orders of Irish-made dresses and to introduce Irish dress into her court attire in London. She also brought the President of the Board of Trade to Dublin to inspect the improvements in weaving that she herself had helped to bring about. These included the production of entirely new types of fabric such as tabouret (a mix of silk and linen), and the weaving of new brocaded Irish dress fabrics on a large scale and to her own designs. Sales of these fabrics were described as ‘unprecedented’, orders came in from London department stores and from trend-setting European women such as the Queen of the Belgians, and Maria rejoiced at having ‘lifted up the hearts’ of the weavers in Dublin’s Liberties.

One of the most impressive of the many initiatives pioneered by these women was the fundraising campaign launched by Frances Anne, Duchess of Marlborough – a grandmother of Winston Churchill – in 1879. Concerned about a deepening agricultural depression in Ireland and fearing a repeat of the Great Famine, Frances launched an international campaign to raise money for those struggling with extreme poverty, particularly in the west of Ireland. In just a few short months, she raised the equivalent of €9,647,606 – an astonishing sum by any standard. The diamond badge presented to her by Queen Victoria, as a token of appreciation for this work, is on display in the exhibition, along with portraits and objects recalling the work of these three women, and many others who served as vicereine across the centuries.

Can you tell us about some of the other vicereines and their initiatives …

Housing, cottage industries and women’s healthcare were just some of the many fields in which Ishbel, Countess of Aberdeen brought about improvements as vicereine. As a committed advocate of Home Rule, she sought to shape a future in which the Irish people could both help and govern themselves. Among her major initiatives was the establishment of Ireland’s first dedicated hospitals for TB patients, at Peamount in Dublin and Rossclare in Fermanagh.

As vicereine, Rachel, Countess of Dudley was an important figure in the development of community healthcare in Ireland. Her pioneering district nurse scheme in remote parts of the west of Ireland in the early 1900s was the forerunner of our modern public health nursing system. Sadly, the west of Ireland was also the location of her death some years later, in 1920, when she drowned while swimming off the Connemara coast.

Were any of the vicereines Irish?

Unlike the viceroys, who were almost always English and, for over 230 years, invariably Protestant, a number of vicereines were Irish-born and several were Catholic. These factors were significant because they enabled these women to identify with Irish perspectives in ways that their husbands rarely could. Henrietta, Countess de Grey was born and raised in Fermanagh and during a visit there, in 1842, she acknowledged her sense of responsibility as an Irish-born vicereine. ‘I pray’, she declared, ‘that I may never prove unworthy of my race.’ In fulfilling that responsibility, Henrietta made an unprecedented number of lucrative official appointments as vicereine.

In the decades leading up to Irish independence, several vicereines became vocal supporters of competing political causes in Ireland. While some were defenders of Ireland’s union with Britain, others supported the campaign for Irish Home Rule. In public and private life, Theresa, Marchioness of Londonderry was an ardent unionist. As vicereine from 1886 to 1889, she worked steadily to develop the craft of lacemaking in counties such as Limerick and Monaghan, thereby highlighting the economic impact of viceregal support and, by extension, the purported benefits of British rule.

The exhibition has sourced many personal objects belonging to these glamorous women – what are some of the exhibits which have fascinated you most and why?

The travelling box owned by Maria, Marchioness of Normanby is, for me, one of the most fascinating and beautiful objects in the exhibition. Made of rosewood, it is lined with green velvet and contains an array of cut-glass perfume and ointment bottles, grooming implements and stoppers with silver tops, all of which are engraved with Maria’s monogram. From this very box, Maria would have applied her make-up, written her letters and arranged her jewellery as she travelled from place to place meeting and greeting people. Her diaries and letters reveal that she was really keen to travel across Ireland and send out a message of respect for people of all religions and political persuasions. In places like Derry, she was so determined to engage with the Catholic community that she carried on with her engagements despite violent protests from some who opposed this impartial approach. For me, this travelling box symbolises her direct and courageous engagement with the people of Ireland beyond the walls of Dublin Castle, even in difficult circumstances. Through the scent bottles and accoutrements, I think we get so much closer to the real personality behind the grand public image too, so there’s a very human dimension to the object. It also gives us a really intimate glimpse into the private world of female beauty and luxury goods nearly 200 years ago. For anyone who loves beauty and beautiful things, this box is a must-see!

Another fascinating object is an ornate vase that was commissioned by women in and around Dublin in 1830, as a gift for the outgoing vicereine Charlotte Florentia, Duchess of Northumberland. Festooned with shamrocks and forget-me-nots, it is made of Irish bog oak, silver, gold, glass and semi-precious stones, and bears the dedication ‘Hibernia Grata / Ireland is grateful.’ It is a riot of colours, textures and symbols, and features an Irish wolfhound, a figure of Hibernia, and a phoenix emerging from a canopy to herald national rebirth. Through its Irish materials, craftsmanship and symbolism, it sends out a strong message of gratitude for Charlotte Florentia’s vigorous efforts to support Irish manufacturers. Chief among these was the establishment of the Irish Ladies’ Patriotic Association for the promotion of Irish textiles. As an object made by Irish hands, commissioned by Irish women and presented to a woman who, as she confessed in her diary, had been ‘so happy’ in Ireland, I think it is a fitting and poignant tribute to the forgotten work of the vicereines.

Need to Know: “Vicereines of Ireland: Portraits of Forgotten Women” is currently on in The State Apartments, Dublin Castle, Dublin 2 until September 5 from 9.45am – 5.45pm daily. Admission is free; www.dublincastle.ie. An accompanying book Vicereines of Ireland: Portraits of Forgotten Women, edited by Myles Campbell, is published by Irish Academic Press; www.iap.ie.

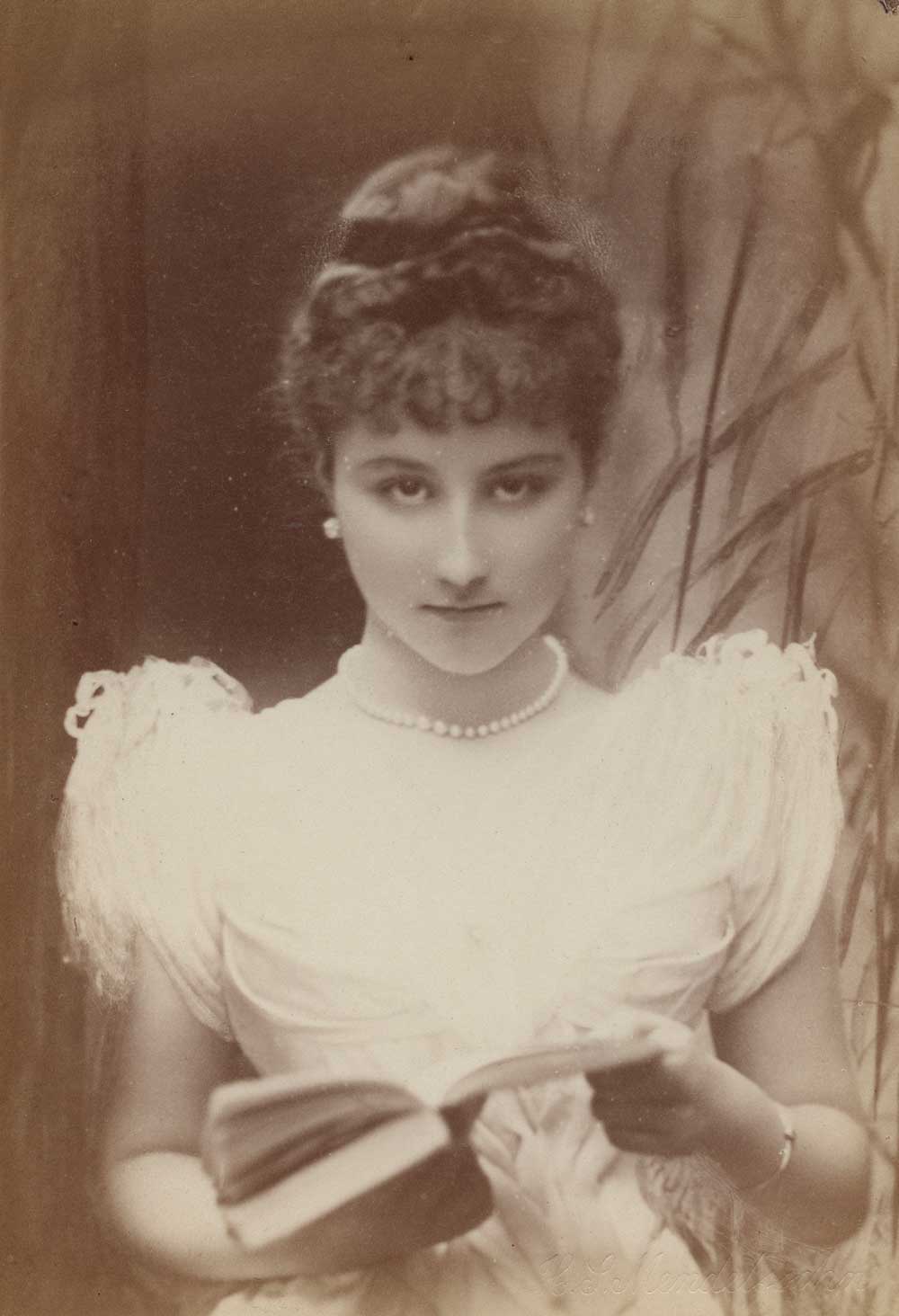

The main featured image is of Alice, Viscountess Wimborne, a strikingly elegant, fashionable woman who revelled in the pomp and circumstance of viceregal life. But by 1915, when she took up her role as vicereine, the pageantry she so enjoyed was looking increasingly outdated as Ireland drifted towards rebellion. This contrast is reflected, in the exhibition, through the inclusion of a grand portrait of her by Sir John Lavery, which hangs beside an original letter written by her in the aftermath of the 1916 Rising. Addressed to her mother, Alice’s letter provides an account of the rebellion from her unique perspective as a woman who, as she put it, ‘saw all’ from within the British administration during Easter week.

LOVETHEGLOSS.IE?

Sign up to our MAILING LIST now for a roundup of the latest fashion, beauty, interiors and entertaining news from THE GLOSS MAGAZINE’s daily dispatches.