They broke down the doors of the old boys’ club, finding a foothold in small brokerage houses before making their way into investment banks and exchange floors. But first, writes Paulina Bren, the female pioneers of Wall Street needed to get dressed …

Maria Marsala, from Dyker Heights in Brooklyn, where working-class Italian Americans famously splurged on Christmas lights and outdoor inflatable Santas, had just been promoted to assistant on the trading desk. It was the mid-1970s and she was about to make $105 a week. Her boss had some thoughts about her style, however: she needed to look more managerial, to dress appropriately for her new position. But what did that even mean? He pointed to her miniskirt and her “hooker boots,” as she called them, the kind that laced up to the knee.

“Go to Wanamaker’s!” She grimaced.

Wanamaker’s was Wall Street’s go-to department store and its clothes were, well, drab. In Maria’s opinion, they “made you look like a guy”. But of course that was the point.

Hoping to find an alternative, she headed to the library to search for books on how to dress in a “managerial” style, but all the manuals and advice books were intended for men. She had no choice: she relented and made the trip to Wanamaker’s like most women on Wall Street, where she purchased a beige-colored suit, a white blouse with one of the floppy bowties so popular in the 1970s, beige tights, and closed-toe shoes. She most definitely looked like a man, she thought to herself as she looked in the mirror at her “ugly suit” that camouflaged her best assets.

Like Maria, most of the early generation of women arriving on Wall Street, comprising an army of support staff as secretaries, receptionists, teletypists, with some plotting to climb the ladder, however steep and treacherous, lived in cramped shared flats and came from backgrounds that were aspirational at best but certainly not wealthy. These young women were clueless not only about how to dress but what wine to order and which fork to use for the salad. They were hungry for information on how to rise in the ranks.

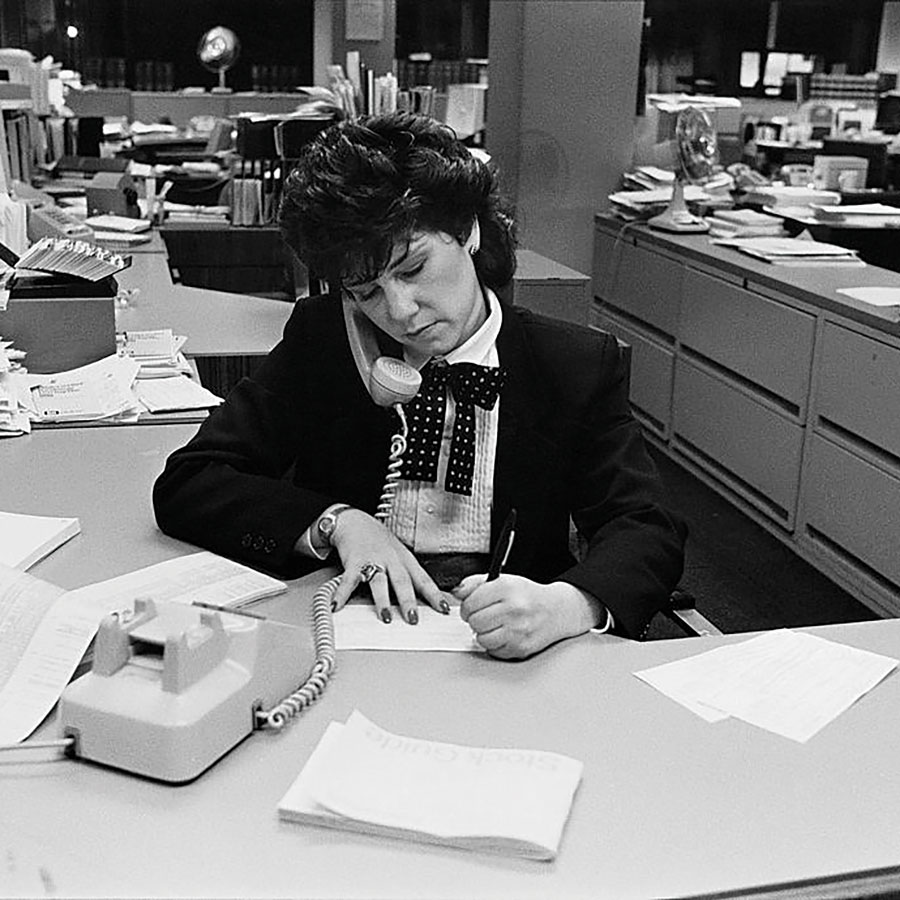

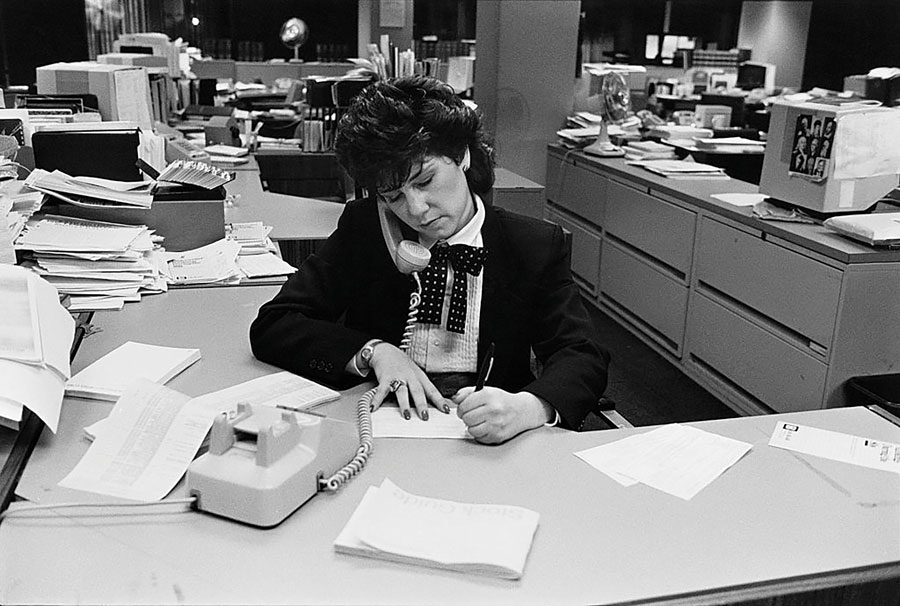

Marilyn Neckes, a stockbroker for LF Rothschild in New York City in 1984

Between Maria’s fruitless shopping expedition and the young women’s desire to get ahead, it was unsurprising that the 1977 publication of John T Molloy’s The Woman’s Dress for Success Book made an enormous splash. It was the very kind of manual that Maria Marsala had been in search of at her local library: it was a how-to for these women coming to Wall Street from working- and middle-class backgrounds.

John Molloy called himself a “wardrobe engineer” – as if he could bring a scientific methodology to how women should present themselves as promotable. Even so, The Woman’s Dress for Success Book became a runaway bestseller. Issues of class were among the central themes that Molloy tackled head-on: “Today hundreds of thousands of women whose parents never went to college are going to college themselves. They’re getting training and degrees that will point them toward the power ranks of American society. But in order to move in, they must do more than arm themselves with degrees and training. They must learn the manners and mores of the inner circle. And the inner circle is most emphatically upper middle class.” Molloy’s plan for rescuing working women by showing them the right and wrong ways to dress was to create for them a “business uniform.” The right uniform would protect and legitimise them.

One of the first women to be admitted to the floor of the London Stock Exchange in 1973

There was “nothing morally wrong with a polyester pantsuit” he wrote, but it was going to tell the world that you were not of the upper middle class. The “imitation man look,” he noted, merely made you look like “a small boy.” A jacket was always to be full cut so as not to outline the bust. Materials were to be wool and linen; patterns, solids, tweeds, and plaid. A designer’s name visibly displayed on a piece of clothing made you look like a “lightweight,” “more interested in form than substance.”

The ideal business uniform was a skirted suit with a blouse in a contrasting colour from the suit. Even as Molloy saw himself a champion for this new breed of women, he stumbled on his own sexism: “despite the rhetoric of the feminist movement,” he declared, “many women, including businesswomen, continue to view themselves as sex objects.” He wanted to see women cover up, to hide not only their backgrounds but also their bodies; just as Maria Marsala had been told to cover up.

Irish woman Oonah Keogh, one of the world’s first female stockbrokers in the 1920s

Some objected. A review in the Wall Street Journal suggested that Molloy was wrong as well as offensive: “Molloy seeks to neuterise women, trading sex appeal for authority. He strips them of colour (he outlaws purple and gold because they symbolise the middle class), of sweaters (they “spell secretary”) and skirts without jackets (it’s a “flag of failure” for the businesswoman). Molloy even advises women to “hang neuter art” in their offices.”

Yet while some were up in arms over his advice, 1970s working women were taking it seriously, rushing out to buy suits in understated colours and accessories that simulated upper-class tastes such as silver and gold pens (never Biros!), pumps over stilettos, and leather briefcases with dial locks. Molloy received the most pushback for his rule that women never wear boots to the office, but he insisted that the research bore this out: “If two women walk into an office, one wearing boots and the other plain pumps, the one with pumps will always be judged more efficient and businesslike.”

Yet he was forced to admit that clothes could not single-handedly destroy presumptions and prejudices. He wrote that women, by existing as women, automatically received second-class treatment everywhere they went and from everyone they met, from “hotel employees, store clerks, receptionists, telephone operators, doctors, and bureaucrats.” He confessed he was no different when he waited impatiently for a meeting with a group of executives, assuming they were men, when all along they had been sitting right there: “Three of the best and most conservatively dressed women I had ever met.” They were following his guidelines to a tee and yet that was not enough to identify them as successful professional women, even to the man who insisted he had discovered the magic formula of an understated double-breasted beige suit!

In 1988, Louise Jones became the youngest woman to own a seat on the New York Stock Exchange

It was no coincidence that in 1977, the same year that Molloy’s bestseller came out, Marilyn Loden coined the term “glass ceiling.” She was working in human resources in the telecoms industry, where she was constantly reminded by her boss to “smile more,” and where she’d been passed up for a promotion more than once because it needed to go to a “family man.” She first uttered the phrase “glass ceiling” while sitting on a conference panel listening to other women attempt to find reasons, including their own failings, for why they were not getting past the middle-management level. Unable to sit there and listen to the self-flagellation any longer, she interjected to say that she believed there was an “invisible glass ceiling,” a ceiling that was cultural and not personal.

Yet Molloy’s advice was personal: you could only have a chance of breaking through the glass ceiling by disguising your modest class background. Even in a chapter called “Dressing to Attract Men,” devoted to time off from the office, Molloy insisted that his research showed that when men saw a woman for only a split second, be it a fleeting reflection in a shop window or a revolving glass door, they had no idea what the woman looked like but they were sure they could identify her socio-economic status.

Head of Wealth Advisory at Goodbody, Michelle O’Keefe (centre), recounts how she was a runner at the Irish Stock Exchange in the 1990s

But hiding or compensating for one’s modest background was a lot more complex than Molloy’s book suggested, especially when you added race, which he failed to address. It did little to help Lillian Hobson, the very first Black woman to enroll in the Harvard Business School in 1967. Later offered a job as a retail broker at a small and women-friendly brokerage house, it was an uphill battle for her to drum up business. When she asked the two other female brokers how they had built their clientele base, they said they’d first sold stocks to their circle of friends and family. But Lillian was from rural Ballsville, Virginia, where no one was looking to get into the stock market.

Molloy’s The Woman’s Dress for Success Book was in many ways a manual for “passing,” a guide on how to come off as if you’d been born with a silver spoon in your mouth. But there was just so much a beige suit fitted correctly around the bust line could do if you were a Black woman in the 1970s trying to climb that ladder. Yet a few years later, at the start of the 1980s, Marianne Spraggins, a law professor to whom Wall Street suddenly beckoned, counselled a fellow trainee at Salomon Brothers. This young woman had arrived on the first day with an Afro and in a hippie vest but within a week had transformed herself, straightening her hair and donning a pinstripe suit. Marianne told her there was no point. For Black women, she said, blending in wasn’t even a possibility and so why pretend? Marianne had created her own uniform, which she would wear defiantly throughout her rise through Wall Street: a blazing red suit and high heels.

She Wolves: The Untold History of Women on Wall Street by Paulina Bren (John Murray), is out now.