The somewhat surprising benefits and freedoms that can come with being an older artist …

In The Advantages of Being a Woman Artist (1988), US feminist art collective Guerrilla Girls famously satirised the benefits women enjoy in the art world when compared to their male contemporaries. Number four on the 13-item list was: “Knowing your career might pick up after you’re 80.”

Many artists I know who have been on the literary or visual art scene for four or more decades – both female and older white males – eventually have to confront society’s nonsensical perception that they are possibly obstructing younger and more diverse artists who hanker for recognition. The unspoken message that it’s good to be youthful and fresh remains powerful – but also excluding for some. However, most of the artists I spoke to recently remain quite sanguine and upbeat on the matter.

“I discovered that being old is like being young again, only this time it is better, because there are no parents telling you what to do.” Liz McManus

Novelist and former politician Liz McManus spoke about new freedoms that have come her way: “I discovered that being old is like being young again, only this time it is better, because there are no parents telling you what to do.” She speaks also of the happy consciousness of waking up each morning and feeling blessed to be able to get out of bed, because “each day, we know, could be our last. That realisation gives life its piquancy and a new vitality”.

The poet and essayist Peter Sirr doesn’t notice much change in his creativity as he grows older. “When I sit down at my desk I’m the same bundle of accident and attempted inspiration that I ever was.” He insists that age shouldn’t enter into it, that “the only interesting thing ever is the quality of the work and plenty of older people are now doing their best work”. Poet Sean Lysaght observes that nowadays we’re very interested in people in their 80s and 90s who have a retrospective, or a book reissued, or the women artists who have shows recognising them after years of neglect. “We love that narrative too,” Sean remarks, “the rewards of just sticking at it, when your art isn’t fashionable, or is overlooked by the art hype machine.”

As Herbert says, creativity hinges to some extent on libido, in itself an imaginative resource, and if the latter doesn’t diminish there’s a good chance that the former will carry on in its experimental way.

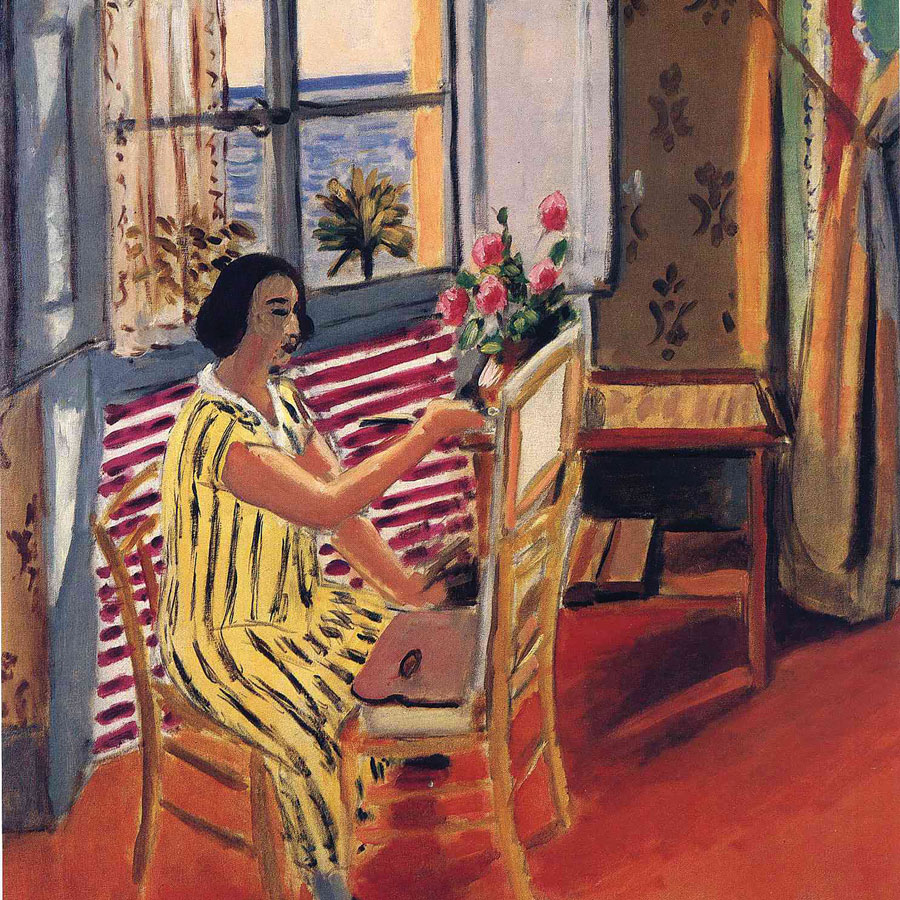

Which brings me to the question of why many older women artists seem to wait in the wings for their creativity to be recognised. Is it possible that PR hype plus misogyny ensures a long wait before genius is recognised? As an old man, Picasso’s creativity wasn’t screened to check if it still measured up, and the Dublin poet and university writing mentor Jean O’Brien notes that some people look on an older woman artist as a “sweet old dear” who passes her time composing “little poems”. She also remarks that Western society is totally hung up on age and youth. What matters to her though is the freedom and knowledge that “one can be creative at any age”.

Visual artist Cecily Brennan has never detected any ageism or sexism in her work. “On the contrary, I find myself working with younger and younger artists. I’m making a film with a brilliant cinematographer, Naoise Kettle, who is 23. All of the crew are under 30. I don’t detect any ageism, or sexism, in any of them. In my experience, it all comes down to the work.”

For those whose cognitive capacities remain intact, the work does indeed go on, give or take the occasional broken wrist, an enlarged prostate here and there, and a load of statins and anti-hypertensive drugs. The short story writer Phyl Herbert spoke about the intersection of creativity and libido in later life, and how in her view “libido can increase as one ages”. Sexual orientation can also change, she says, in itself a creatively transformative turn of experience. She recounts how a woman friend, spending time with her cousin in France, was gifted a very up-to-the-minute vibrator on her 80th birthday. As Herbert says, creativity hinges to some extent on libido, in itself an imaginative resource, and if the latter doesn’t diminish there’s a good chance that the former will carry on in its experimental way.

Everyone over 60 should treasure their hard-won bank of experience, honour the wisdom harvested both through mistakes and good decisions …

In life and in art, one can rarely go too far. James Joyce knew this. Yeats knew it. And contemporary older artists, just like Cecily Brennan, Peter Sirr, and Jean O’Brien know this. Personally, I believe that everything hinges on imaginative drive, and that artistic work continues until the body, that great dictator, tells us the game’s up. Everyone over 60 should treasure their hard-won bank of experience, honour the wisdom harvested both through mistakes and good decisions, and consider how here in Ireland we stand enriched and in a position to give to younger others – should they wish to hear us. If they don’t, it doesn’t matter. The young are as much on their path as we are on ours, and in the end only the gift of human experience can serve any of us, not our life number.

Walking with Ghosts, a new short story collection by Mary O’Donnell, is published by Mercier this month.