Happening upon a collection of letters from Ernest Hemingway to an Irish Brigadier led Lavinia Greacen into the unusual career of military historian …

In the early 1980s, Lavinia Greacen was writing freelance features, working part-time as a publisher’s rep, writing an agony aunt column for Woman’s Way, and juggling, with her husband, the responsibilities for their three children. One weekend, the family were staying with their friend Christopher O’Gowan, who lived at Bellamont Forest in Cootehill, Co Cavan, when she went down with flu. “I had a high temperature, bad headache, and endless coughing, so spent the weekend in bed – a rather wonderful four-poster – while everyone else carried on. Christopher came in one morning, put something down, and I heard him say, ‘While you’ve nothing to do, you might like to read these.’” Curiosity made her sit up and look. There on the end of the bed was a pile of opened envelopes with American stamps addressed to his late father, Eric Dorman O’Gowan (later known as “Chink”), who she knew had been a British army officer. The intimate letters inside turned out to be from the writer Ernest Hemingway, and the two men, she was astonished to find, had been lifelong friends and correspondents.

This cache of letters flicked a switch, and since Greacen was doing occasional pieces for The Irish Times, with Christopher’s permission, she mentioned the find to then editor, Douglas Gageby. “He immediately said he was mad about Hemingway and he could do a series of spreads on them.” It was an excellent editorial call, and prompted contact from a London publisher wanting a book. The result for Greacen would be the biography Chink, which drew widespread critical attention, and would lead to two acclaimed books about the novelist JG Farrell, one a biography and the other his collected letters, which went on to become a Sunday Times Book of the Year.

Chink was a layered and complex character, a tricky enough subject for any biographer.

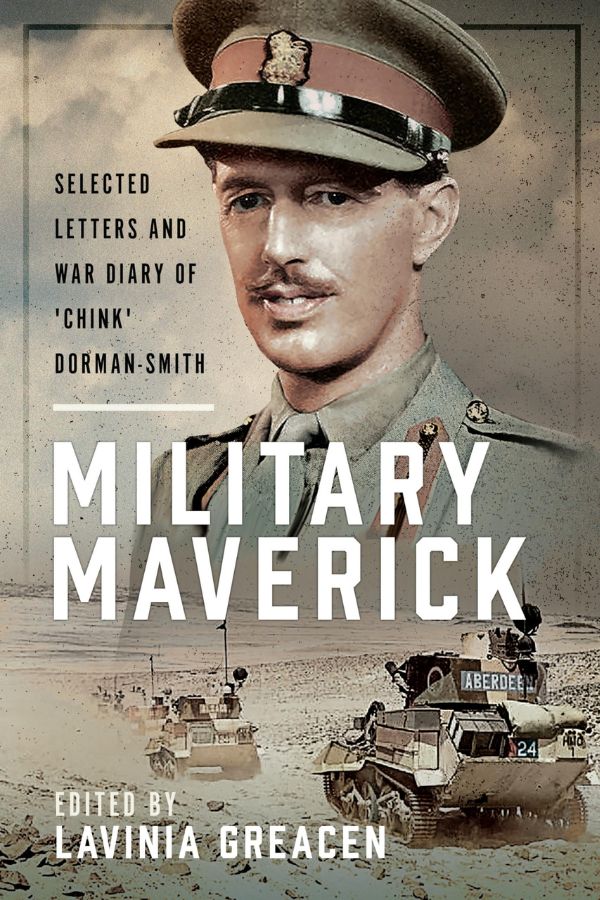

In isolation during Covid, her children having long flown the nest, and a few years after her husband’s death, Greacen thought again about Chink, and pulled out from under her desk the trunkful of his papers still in her care. Among them were myriad wartime letters to his lover in which passion gave way to acutely observed day-to-day happenings. The warm reception to Farrell’s letters gave her an idea. She began the long and laborious work of transcription, and then the shaping of her latest book, Military Maverick: Selected Letters and War Diary of ‘Chink’ Dorman-Smith.

The desk and the now empty trunk are in Greacen’s study, a room which has had previous lives as bedroom to each of her children in turn. Three decorated ceramic nameplates remain on the door, because this is not a house in which the past is stripped away and painted over. It is here in the present, in the bookcases and on the walls, in the family photographs and collected objects, as well as in Greacen’s work as a biographer and military historian.

Greacen we will claim as a Dubliner. Born in England, to English parents, she has lived here for over 60 years. She arrived in 1963, newly married to Walter, a Monaghan man she had met in London, and the couple bought the pretty, whitewashed house in the Dublin mountains where Greacen still lives and works. Her study opens into a conservatory, filled like the rest of the house with books and pictures, and surrounded by a large and well-wooded garden. Nature thrives here. A red squirrel lunches in a tree. A deer may wander past, or stop and stare. Inside the house is Hazel, a sweet and polite Maltipoo, alert but quiet.

SEE MORE: A Secret History – Irish Women in Business Throughout History

“Now, we talk. Delving, asking, how do you feel, always reaching inside ourselves for wounds and vulnerabilities. They coped by not feeling, in a way, they deliberately shut that door. I don’t know which is best, frankly.”

Chink was a layered and complex character, a tricky enough subject for any biographer. Even his name has to be glossed: born Dorman-Smith, he later changed it to Dorman O’Gowan to emphasise his Irishness; his nickname referred to his resemblance to the Chinkara antelope on his regimental mascot. In later years in his home town of Cootehill he was known as the Brigadier, or the Brig. He had a privileged childhood, and it was then that the many dualities in his life were rooted. Although he grew up in a Palladian villa, and spoke in a voice not out of place among the landed gentry, his grandfather had started out more or less selling bits of coal gathered off the dock at Liverpool. He was a Catholic, like his mother, but she had so hated the production of his baptism that his younger brothers were Protestant. In Ireland, he was considered Anglo-Irish, in England, Irish. Public school was followed by Royal Military College Sandhurst, the Northumberland Fusiliers in 1913, where his nickname Chink began, and the hell of the first World War.

“Today,” says Greacen, “he probably would have suffered depression and inner turmoil. But I remember, growing up, my own father had been all through the first World War [in the RAF], and didn’t talk about it. People didn’t. They packed it away. Now, we talk. Delving, asking, how do you feel, always reaching inside ourselves for wounds and vulnerabilities. They coped by not feeling, in a way, they deliberately shut that door. I don’t know which is best, frankly.”

She realised how deeply those first experiences of war had affected his thinking on strategy, and his reflective, progressive approach to tactics. Chink’s time in the trenches convinced him that army strategy needed new thought, not just to win, but to protect its soldiers. For him this meant outwitting the enemy, and therefore taking them by surprise. “He believed in the chess game approach, and in committing fewer men to the risk of death.”

SEE MORE: Louisa Treger Heralds The Work Of Four Forgotten Heroines

“My privilege – after a while, not at first – was that I was spoken to as a fellow soldier.”

As his own words in Military Maverick reveal, he held senior appointments in England, Egypt and India, but had to leave his wife Estelle behind when appointed head of the Haifa Staff College in Israel in 1940. There he met and began an affair with Eve Nott, whom he would eventually marry. By then he had so impressed Claude Auchinleck, who in 1941 became Commander-in-Chief, Middle East, that within six months Chink would be summoned to GHQ in Cairo as the “Auk’s” chief advisor.

In the critical summer of 1942 the two were instrumental in stopping Rommel’s advance across North Africa towards the oil-rich Nile Delta in what would become known as the First Battle of Alamein. But Chink and Auchinleck were sacked by Churchill in August, so that it was Montgomery who led the British to victory in October. Military Maverick shifts the historical focus, aided by contributions from military historian John Lee, and argues that the first battle during June and July was the pivotal one. Unorthodox strategy had triumphed.

In person, Greacen herself is kind, curious, energetic company. She is a conversationalist, not of the exhausting, performative sort, but of the generous, stimulating sort. She describes herself as “terribly shy and self-conscious, not one of those people who happily talk about themselves”, but it would be a mistake to link that shyness to any lack of confidence in her work. She knows, as any biographer ought to, that she can rely on the meticulousness of her own research, and she has an enviable sureness of touch when it comes to plucking out what is quotable, what is defining, and for seeing her subject in the round. She speaks and writes fluently about army matters, the fruits of a research methodology which has combined careful study with speaking to as many of Chink’s fellow officers as possible. “My privilege – after a while, not at first – was that I was spoken to as a fellow soldier.” How did she develop the rapport and the trust needed to reach that point?

“Well, you’re either yourself or not. I remember, for instance, Chink’s brigademajor at Anzio. He’d been very confident on the phone and asked me to meet him in his club, as they often did. I knew he’d been having lunch so I just said, what did you have to eat? We talked about food, and after a while we talked about all of the other things. You meet them as a person.” Some were more reluctant. “One of the very early generals, who had been in India, wouldn’t see me at first. He said, no, my opinion about Chink is well-known at this point. So I offered to send him a copy of a favourite book, and raffle tickets, so he could sell them for the Army Benevolent Fund. He said oh well, that’s an interesting idea. And he did see me. I didn’t change his opinion, but he did show me an enormous amount about the army in India, how it worked, all the stresses and rivalries.” Greacen subsequently spent time researching in India, and when she found herself in one of the hill stations he had been in, she sent him a postcard. “I wrote: I’m thinking of you. Here I am, and it’s just same. He got it about two months later, and was thrilled, he said he hadn’t had a word from India for ages.”

SEE MORE: Acts Of Activism – Liam Cunningham

“There are many women now in the army, a greater proportion of them, and as more women experience war they will write about it. I hope they do, because women bring something different to the work.”

People respond to sincerity of interest and a readiness to connect. The idea of lunching with seasoned generals and field marshals to discuss wars past still seems an intimidating one, and I wonder whether Greacen thinks this is something that might be deterring women from researching and writing military history. There seem to be so few. She disagrees. Nor does she think it is a question of women being excluded by the military establishment.

“I really think it’s women not wanting to do it, women not being drawn to write or read about battles. This is a generalisation, and people will fight me and say that’s quite wrong. They’re quite entitled to disagree! But there are many women now in the army, a greater proportion of them, and as more women experience war they will write about it. I hope they do, because women bring something different to the work.” What kind of thing? “Well, empathy.”

Of course some women are already at work in the field, and in this context Greacen mentions Lindsey Hilsum, who wrote a biography of Marie Colvin, In Extremis. Colvin was the Sunday Times foreign correspondent killed in Syria in 2012; Hilsum, a war reporter for many years, is Channel 4’s international editor. Her source material included Colvin’s 300 notebooks and diaries. “Extraordinary. An incredibly busy woman too, she still has to file reports every night, and yet she did so much. It was a biography, but it was also about the emotional reality and other pressures which were brought to bear. So there is that, slightly different, angle.”

One of the highlights of 2025 has been Greacen’s presence on the shortlist for the International Templer Prize. For military historians, this is like being shortlisted for the Booker, but women are still vanishingly rare, and Greacen was the only woman to feature on the shortlist. It’s a whopper of a pat on the back from the military establishment. She reminds me, though, that it wasn’t the history of battles, but Hemingway’s letters which brought her to Chink in the first place. “Had there not been that angle, to be frank, I doubt I would have got there. I knew the outline of his life, and I interviewed all his relations, but the publishers said, well you do realise you’ll have to study tactics and strategy. I said, What? But then I thought, well, I have to plunge in. And so I plunged.” She can’t recommend the risk enough.

Military Maverick: Selected Letters and War Diary of ‘Chink’ Dorman-Smith, Pen & Sword Press, is out now.

SEE MORE: Feminism In Ireland And The Women Who Paved The Way