This International Women’s Day, celebrate the often forgotten women whose stories shaped not just the past, but also the future …

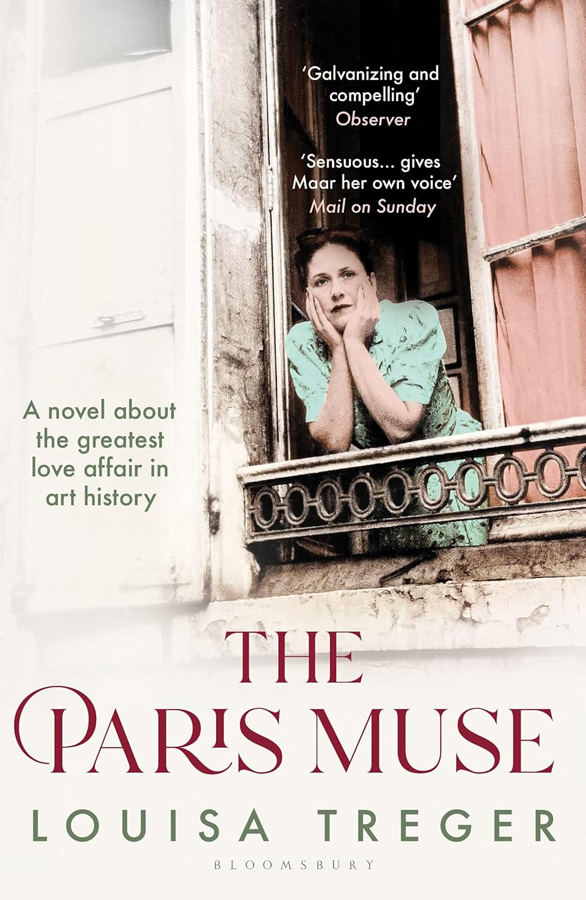

Image: Dora Maar in her studio in Musée Picasso (Paris, 1944) © The Cecil Beaton Studio Archive at Sotheby’s

Dorothy Richardson

I began writing about trailblazing women by chance. While researching Virginia Woolf for my thesis, I discovered the writing of her peer, Dorothy Richardson, a personality I found so extraordinary that she inspired my debut novel, The Lodger.

Dorothy defied societal norms, embarking on affairs that broke taboos, including a relationship with the married HG Wells, and a same-sex relationship in an era when homosexuality was illegal. Her literary innovations were equally bold – she pioneered stream-of-consciousness before James Joyce or Virginia Woolf. When her first novel was published in 1914, its radical, free-flowing form shocked the literary establishment.

Lady Virginia Courtauld

My second novel, The Dragon Lady, unfolds on a vast international scale – from the glamorous Italian Riviera before the Great War to the Art-Deco splendour of Eltham Palace in England, and the eastern highlands of Rhodesia (now Zimbabwe). This story too began by chance. In 2016, a friend mentioned a “secret Monet” allegedly hidden in Zimbabwe’s National Gallery to protect it from then-president Robert Mugabe. On a trip to Harare, I saw works by Renoir and Dürer, part of a collection donated by Virginia Courtauld and her husband, Sir Stephen Courtauld. In total, they had given 93 works, including pieces by Rembrandt, Goya, and Pissarro.

However, access to information was blocked, raising unsettling questions: had these artworks been hidden for safekeeping or seized by Mugabe’s ruling elite?

This mystery led me to write a novel based on the life of Courtauld, a woman as unconventional as Richardson. At her Catholic school, she put mice under the nuns’ habits. In her late teens, she got a black snake tattoo, rumoured to end in a place only her husband knew! She lived a life of adventure and political activism across Europe and Africa. “She was full of character and life,” said her niece, Margaret Bernard, following her death, aged 77, in 1972. “She didn’t care what she said to anyone, or what she did.”

Nellie Bly

This fearless spirit also defines the heroine of my third novel, Madwoman – America’s first female investigative journalist. In the late 19th century, women reporters were limited to fashion, arts and society gossip. Determined to change this, Nellie devised an audacious plan: she feigned insanity to infiltrate an asylum and expose the appalling conditions. Her subsequent articles sparked outrage and led to major reforms. Beyond improving mental healthcare, Nellie revolutionised journalism, pioneering investigative reporting and creating space for women in the field.

The subject of my latest novel, The Paris Muse, Maar is probably best known as Picasso’s muse and lover, but she was much more than the “Weeping Woman” he immortalised.

Dora Maar

A pioneering photographer, painter, poet, and political activist, she exhibited at the Museum of Modern Art in New York before she met Picasso in 1936. Her photographs are radical and fantastical.

Her nine-year relationship with Picasso was tumultuous. A notorious womaniser, he was involved with another woman, Marie-Thérèse Walter, when he met her. He merged their features in his paintings as he viewed all of his relationships as material for his art. Dora challenged him, influencing his politics and his masterpiece, Guernica. However, when he left her for Françoise Gilot in 1943, she suffered a breakdown and was treated by the psychoanalyst Jacques Lacan. Though she eventually found solace in religion and continued working until her death in 1997, her legacy remains overshadowed by Picasso’s.

Creativity unites them: writing, photography, painting, decor and design.

The four books differ in tone, but share overlapping themes beyond their defiant heroines. The overall focus is on women’s experiences; men being either irrelevant, obstructive, even harmful. The protagonists face severe constraints, particularly regarding their bodies. Richardson cannot treat sex as casual fun like Wells. Virginia Woolf and Maar battle infertility, while Bly circumvents the issue by delaying marriage – a decision tinged with loneliness.

Societal pressures manifest differently for each. Richardson is ensnared by the sexual double standard that condemned women’s affairs, while excusing men’s. Courtauld’s wealth cannot shield her from society’s disapproval, and Bly’s intellect and ambition are blocked by the narrow-minded male gatekeepers of journalism. Despite her artistic success, Maar finds herself trapped in a male-dominated creative circle.

There are severe psychological pressures on women operating in a man’s world.

Richardson’s mother commits suicide. Both Virginia and Maar experience mental breakdowns, and Madwoman unfolds in an asylum. Bly’s investigation revealed that many patients weren’t mentally ill, but were merely inconvenient to society – women who married without parental consent, refused marriage or were abandoned by husbands. The asylum was a socially acceptable way of disposing of women who did not conform. This disturbing discovery made me reflect on the conservatorship that controlled Britney Spears’ life for 13 years, echoing these historical injustices. Society still struggles to accommodate women who refuse to fit its mould. Language itself reflects this: assertive men are called strong and confident, while women are dismissed as bossy or shrill.

Writing my novels has shown that while some progress exists, many battles remain. Women in Islamic states still face extreme oppression. Closer to home, domestic and sexual violence, workplace discrimination, and the gender pay gap persist. The fight for equality is far from over, which is why I write historical fiction. I want the achievements of my heroines to be recognised and their voices amplified. But I also seek to highlight the patterns that continue to shape our present. History is a living narrative, and these stories demand to be told.

The Paris Muse by Louisa Treger is out in paperback on March 27, published by Bloomsbury. @louisatreger

SEE MORE: Feminism In Ireland And The Women Who Paved The Way