The Guinness family’s bashes were the highlight of 1880s social life, with invitations the hottest ticket of the time. A new book by Arthur Edward (Ned) Guinness is full of fascinating details …

No-one threw a ball as splendidly as Adelaide Guinness. An ordinary person, hurrying along the south side of St Stephen’s Green on a dreary February evening in the late 19th century, might have been caught up for a few moments in a rustle of silks and a swirl of eau de cologne as the sparkling set were handed down from their carriages at the steps of number 80.

St Stephen’s Green, c1890s, with number 80 visible.

Inside, Adelaide filled her elegant rooms with ferns and giant palms, white roses and lilies, and piled the mantels with rarely seen exotics: zebra-striped dragon trees, golden jewel orchids. At eleven o’clock, music rose over the hum of well-bred voices, and as they began to dance, the ladies showed off the movement of their dress fabrics. Delicate tulle skirts paired with satin bodices were all the rage in 1880, in fashionably deep red or heliotrope trimmed with contrasting pale yellow or white blossoms. Supper at one o’clock was welcome fuel, and the most energetic guests danced until four or five, when sleepy drivers brought the carriages to the hall door again.

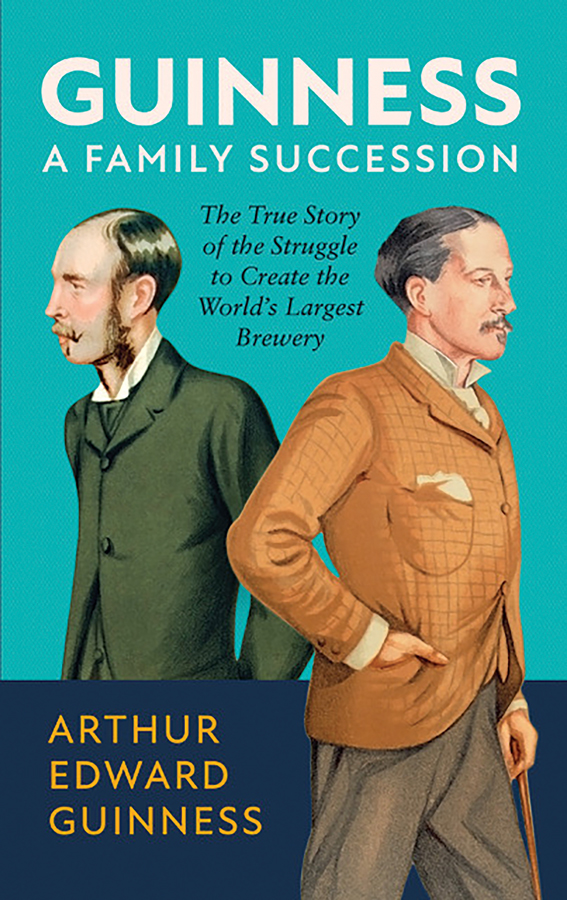

A caricature of Edward Cecil Guinness, Lord Iveagh, by ‘Spy’ in Vanity Fair, 1891.

When Edward Cecil Guinness, the first Earl of Iveagh, died in 1927, it was widely estimated that he was the richest man in England or Ireland. Fifty years earlier, when he married his cousin Adelaide Guinness, he had recently inherited the family brewery jointly with his brother Arthur (later Lord Ardilaun) from their much-loved father Benjamin Lee. Edward Cecil – Ned – had also inherited the family work ethic, and for nearly 20 years gave himself over to improving and expanding the brewery. Even after its public sale he always remained conscious of, and connected to, the source of his fortune.

The Guinness brewery viewed through the entrance on James’s Street, c1840.

A family legacy of this kind could be a burden as much as a privilege, but however much this preoccupied Ned, the centre of his world was Adelaide. Once married, they settled down, if you can call it that, at the St Stephen’s Green mansion (now Iveagh House and home to the Department of Foreign Affairs) where he had grown up. It was an ever-expanding address that would eventually incorporate numbers 78, 79, 80 and 81. The young couple also had a flat in Berkeley Square, and a new purchase, Farmleigh, a country house in the Phoenix Park, a couple of miles from the Viceregal Lodge (now Áras an Uachtaráin).

Adelaide and Ned in fancy dress at a ball at 80 St Stephen’s Green.

Ned and Adelaide did not go in for the wholesome regime of early suppers and family prayers on which Benjamin Lee had thrived, but knowing how to party did not make them sybarites. They were thoughtful and hard-working, keenly aware of those less fortunate: Ned, in particular, would steer a lasting programme of social care and housing in Dublin and London. In his personal affairs, despite his ever-increasing income, he maintained the careful habits of his forebears, gently querying household gas bills, and tracking the cost of newspapers. In private, Adelaide dressed plainly, wore no jewels, and surrounded herself with animals, paintings, and flowers.

Portrait of Adelaide Guinness by George Elgar Hicks.

Farmleigh, intended as a country bolthole, was close enough to town to be practical for a man whose mind never fully disengaged from work. Ned and Adelaide first stayed there as newlyweds. They strolled through the Park together each day, Ned crossing the Liffey to work, and Adelaide spending the day in town. Sometimes she drove a little open carriage to meet him coming home: a favourite simple pleasure.

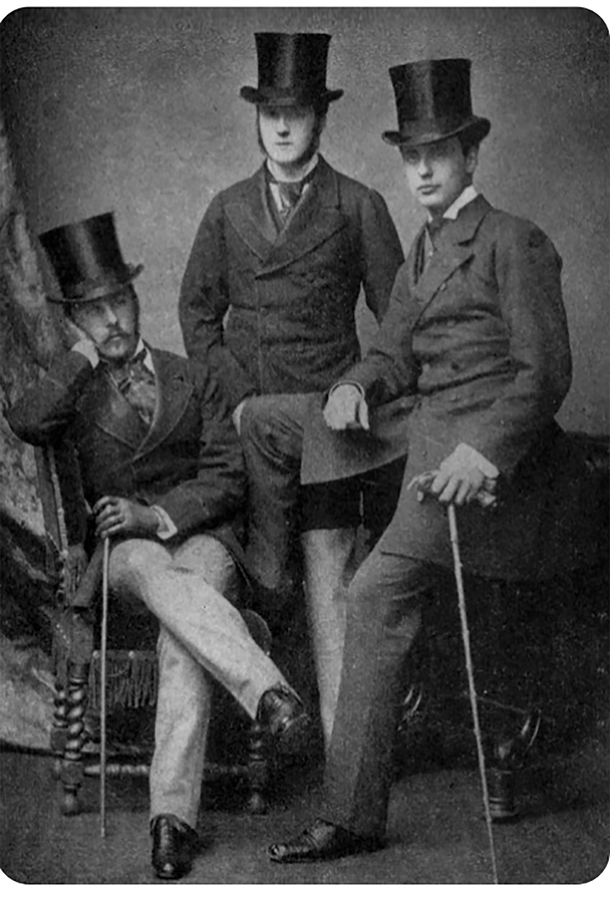

Brothers Edward Cecil, Arthur and (Benjamin) Lee, c1870s.

But back to the balls. Whether at Farmleigh or at 80 St Stephen’s Green, Ned and Adelaide received invitations to everything, and naturally sent out their own. The Dublin season centred on the nerve centre of the British administration, Dublin Castle, where the Lord Lieutenant held court. There were levées and drawing-rooms, parties and balls, and the annual procession of débutantes in white dresses and trembling ostrich feathers.

“Castle Season” began in January and ended in March after Trooping the Colour and the St Patrick’s Ball, just in time for everyone to decamp to London for the season there. Sporting events loomed large, and as Castle Season closed, Ned and Adelaide turned their minds to racing at Punchestown. They loved a good two-day house party. Lunch was sent ahead to the racecourse, to be laid out on linen-and-silver-set tables. One thirsty party of 18 polished off, over two lunches, 32 bottles of champagne, six of sherry, twelve of light claret, and two of curacao. It’s astonishing that all they lost on the racecourse was five knives, a metal goblet, and Arthur’s hat.

Number 80 St Stephen’s Green, now Iveagh House.

Ned loved driving, and often drove to Punchestown himself, but he liked to do it at speed, and Adelaide may have been relieved (or behind it) when the coach gave way to the Viceregal train. A whole carriage was reserved for their Punchestown party of up to 20 people. The Viceroy’s private compartments were chalked with “His X”, for His Excellency, and a Guinness family story commemorates the witty railway porter who once chalked on Ned’s “His XX”, a reference to the Guinness Extra Stout label. It was Ireland, after all, and you wouldn’t want to be developing notions.

Within a few years of their marriage, the Guinness balls rivalled the Viceregal efforts in their extravagance and in people’s desperation for invitations. The society columns hungrily picked over the details, from the choice of flowers to the pages of Burke’s Peerage come to jostling life in the ballroom. They didn’t shrink from breathless analysis of the costs (reckoning one ball at £4,000), nor from fanning the flames of what they prayed would evolve into a keen rivalry between Adelaide and her sister-in-law Olive.

St Patrick’s Cathedral and Park in Dublin 8, respectively restored and laid out by the Guinness family.

The fashionable set couldn’t sleep a wink in 1881 for worrying whether they would get the nod for Adelaide’s next set piece. It would be a good year, with brewery profits up to nearly £400,000 and Ned’s income from it (by now he was sole owner, having bought his brother Arthur out) over £300,000. Party budgets were not problematic. Adelaide opened the season with a ball, and threw another, fancy dress, nine days later. While individual hearts may have sunk at the inescapable expense and effort, the press called it a patriotic act and a stimulus to trade. It was an unusual spin on a party, but orders would flow from Mrs Guinness’s thousand guests to milliners, tailors, and anyone selling a bolt of satin.

The Iveagh Markets on Francis Street in Dublin 8.

Ned had two outfits on the go that night, the first a vintage Florentine, the second a Cavalier. Adelaide was resplendent as Madame de Pompadour. The guests and their dressmakers rose to the occasion. The Viceroy came as Cesare Borgia, while others represented Mary Queen of Scots, Henry IV, Marguerite de Valois and a piece of white Dresden China. Everyone played the game, though not all opted for glamour: Lady Drogheda went as Old Mother Hubbard, with Major Frank Foster as her dog. Vanity Fair reported that in Dublin, everybody was in the best of tempers. Everybody at the party, perhaps.

Sons Rupert, Ernest, and Walter made Ned and Adelaide’s a family of five. The pattern of life was winter in Dublin, until Punchestown, Farmleigh over Easter, London for the season, Cowes for sailing, shooting in Scotland into the autumn, and home to Dublin. Ned maintained strict daily contact with the brewery even when he was away from Ireland. Change was looming, though, and in 1886 it became a public company, catapulting the family from simply rich to fabulously rich.

A shooting party at Elveden in December 1901, with guests including the future King George V (at the wheel of the car on the left).

Ned wanted somewhere he could shoot, and so they bought Elveden Hall in Suffolk, formerly owned by Maharajah Duleep Singh, who had modelled Elveden’s interior on a Mughal palace. Among its beauties is the four-storey high Marble Hall, entirely made of white Carrara marble. Ned and Adelaide instigated shooting parties on the huge estate, bringing together friends from philanthropic, political, and business circles, and fussing appropriately over the Prince of Wales, later George V, who loved Elveden shooting.

Adelaide did not live to see Ned become the Earl of Iveagh. She died at Elveden in 1916. For the rest of his life Ned kept her bedroom as it was on the day she died, to the very flowers that stood there. They had always been Adelaide’s favourite way to decorate a room.

Guinness: A Family Succession – The True Story of the Battle to Control the World’s Largest Brewery (Scala) by Arthur Edward Guinness is out now.