The perils and occasional pleasures of being a member of the Precariat …

I never really wanted to have a job. Not a proper one, anyway. As a result, I’ve spent the majority of what might be called a career as a member of the social class known as the Precariat. This has involved some unexpected shifts in direction, a couple of dead ends, a lot of freedom and no small amount of insecurity. So when I think about the coming age of AI, which appears to herald the end of most jobs, I cross my fingers and hope I’ll be able to adapt yet again.

Considering everything I’ve already done for work I see a potted, chequered, and inconsistent career, with all the swings and even more roundabouts. I blame Transition Year. It was so much fun it ended any academic ambitions I might have had – we got to put on plays, publish newspapers, and even make a film. I wasn’t sure what I wanted to do in life but hoped it might be something like that, and ideally something that didn’t need me to pass the Leaving Cert.

It’s quite possible that by pursuing different professions, with varying degrees of failure and success, I’ve been subconsciously trying to turn my life into one long Transition Year. Seeing this pattern of constantly adding new strings to my bow made an old friend start referring to me as a Polymoth. At first I thought this was just an endearingly daffy Spoonerism, then I realised she had a point – I do have a tendency to fly heedlessly towards whatever shiny new thing is glinting in the distance. This is perhaps best illustrated by a conversation I had with a film producer friend, just after I’d made my first short film. “I spent my 20s as a fashion photographer, and my 30s directing ads,” I told her, “and now I’m going to spend my 40s making films!” “Great,” she replied, “and you can spend your 50s trying to buy your house back.”

This was the beginning of a great love story with photography that has continued to this day, despite AI’s current attempts to muscle in on my turf.

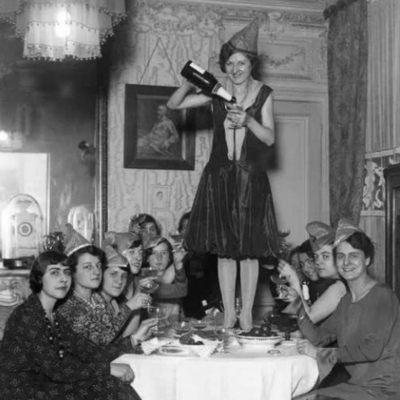

Let’s start at the beginning – after leaving school early to be a teenage punk in London, I landed on my feet and was soon the head (and only) waiter of a Knightsbridge greasy spoon café. We had a varied clientele, lots of builders, a couple of dancers from the Royal Ballet, and two wonderfully polite Japanese businessmen who would regularly come in for the full English fry, which they seemed to find particularly exotic. They didn’t have a word of English between them and told me via sign language, bowing and smiling, that they would have everything. One memorable day in the middle of the lunchtime rush I completely misjudged my velocity as I hurtled down the stairs towards them, barely balancing their heavily laden plates. The plates hit the table and the laws of physics dictated that the food kept travelling, a veritable tsunami of burgers, beans, eggs, and chips sliding over the edge and onto their impeccably dressed laps. They kept nodding and bowing throughout.

It seems I was never going to be suited to a career in hospitality, but working in the café did give me two things that would prove very useful later on. The first was the waiter’s skill of observing everything going on around me, which helped a lot when I later became a photographer. The second was a camera, brought in by a pretty shady character on a Friday afternoon just after I’d been paid. One quick transaction later, I was the proud owner of a shiny new Pentax of dubious provenance. This was the beginning of a great love story with photography that has continued to this day, despite AI’s current attempts to muscle in on my turf.

A while later, I moved to Germany, where I had a brief stint as a semi-pro langefinger (a great German term for shoplifter). I can still see myself slinking out of the KaDeWe department store into the hot Berlin sun, sweating conspicuously under a borrowed winter coat that reached down to my ankles and made strange clinking noises from the various bottles I’d hidden deep in its pockets. Thankfully, I wasn’t caught. A little later, I found a different source of income – selling a litre of my blood for 40 deutschmarks, which kept me going for quite a while.

No doubt AI is already conducting job interviews, and I’m glad that a tangible benefit of being an upstanding member of the Precariat is I’ve been subjected to very few of them.

I then got a gig driving an eccentric geophysics professor around the country in a VW van, even though I’d never driven anything that big before and my driving license was only a month old – I could barely drive on the left let alone the right. The first clue that I might not be a consummate professional came when I picked up the van from a hire place, drove it around the corner and straight into the back of a large BMW which had stopped suddenly at the lights. After I’d convinced the police that the odd-looking document I was waving at them was in fact a driving license (all the Irish writing and the absence of a photograph had confused them), I drove very carefully back to pick up another van. Luckily, the rest of the job went fine, until later that year when a summons arrived at my squat to attend the court case to settle the accident. I’d already booked my bus and ferry tickets home, so didn’t bother going and thought no more about it. That is, until I suddenly remembered the whole farrago with horror while queuing for passport control in Frankfurt in the mid-2000s, the first time I’d been back to Germany since going on the lam. Thankfully, they didn’t have AI facial recognition yet, so I wasn’t greeted with a “Ah, Herr Horgan, ve heff bin expecting you” before being marched off to a windowless room for an uncomfortable interview.

No doubt AI is already conducting job interviews, and I’m glad that a tangible benefit of being an upstanding member of the Precariat is I’ve been subjected to very few of them. One exception was a couple of years ago when I was living in Paris – paid work was particularly scarce, so I decided it might be wise to try getting a regular income. A friend put in a good word, and off I went for my first job interview since I was a teenager.

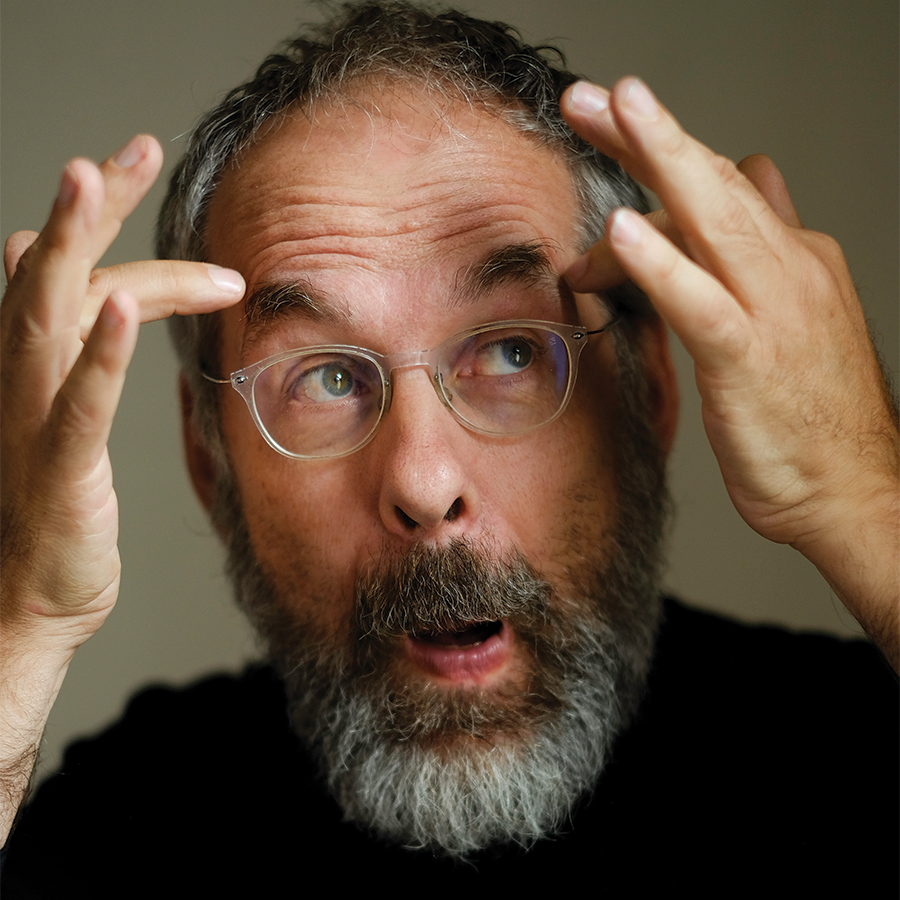

WILL AI STEAL HIS JOB? When Conor asked AI to create a image of Irish drag queen Panti Bliss “in the style of photographer Conor Horgan”, this is what he got.

I tried to maintain an open mind about the interview, which was for a part-time film lecturer job in Europe’s biggest private film school. The first inkling that I possibly wasn’t a great fit was when the head of the school asked me what I’d like to teach the pupils beyond the syllabus. “That’s easy,” I replied, “I’ll teach them how to deal with failure.” This is a vital skill that’s rarely referred to in education, especially in the arts. I could see from his glowering Gallic expression that this had not gone over at all well, and as far as he was concerned every one of his students was a mini- Spielberg in the making. I must have then said something right as he started to smile and told me that even though I was being interviewed for a part-time position, if things went well, it could very easily become a full-time one. It was my face’s turn to fall, with his quickly following suit. We silently agreed that this gig was not for me and I returned to Paris, thinking non, je ne regrette rien.

But what do I regret? Following my dreams. Well, not all of them – some of the dreams I had were absolutely ludicrous, and enough of them have come true by now that I can say I’ve both been a disappointment to myself and exceeded my wildest expectations – no mean feat. However, I do still regret one particular dream – or to be more specific, one particular screenplay that I wrote and obsessively rewrote for almost a decade. In hindsight, it wasn’t the slam-dunk introduction to the Hollywood money I’d hoped it to be, so when I eventually gave it to the producers I was pleasantly surprised when they got in touch after only three weeks (in the film world, this is equivalent to the phone ringing back before you’ve even put it down). So much of working in film is waiting for someone to read the thing, decide if they want to be in the thing or invest in the thing. The producers were calling to let me know they loved the thing, and the only problem was that it was too big (meaning expensive) for me to direct. This meant it would need to be given to a more bankable director, and that my only compensation for the years of toil would be an eye-wateringly large cheque. I was, quite frankly, okay with this.

If there weren’t going to be any solutions to potential unemployment from past experiences, maybe I should consider what underused assets I have.

Unfortunately, the project was not handled well and fell at the final hurdle before it could secure production funding. I had been used to my screenplays either curling up and dying on their first exposure to daylight or going on to actually get made, so this was an entirely new and not very pleasant experience. I’d already followed this dream for far too long, and knew if I wanted to keep following it, there was only one real option: sell my house and rent a converted garage in an unfashionable part of LA to spend the next five years pushing the project uphill – and then, and only if I was very lucky, end up with not enough money to make it properly. My producer friend was right. I let it go.

While not necessarily done with making films, at least the arty no-budget kind, I was definitely done with the film business. Again, no regrets, especially as I’m keenly aware that before long, AI will be able to churn out entire films – truly awful films, it must be said, but there does seem to be a market judging by how many are already being made. So I had one less thing to worry about, and could continue my career trajectory of getting better and better at things that paid less and less.

If there weren’t going to be any solutions to potential unemployment from past experiences, maybe I should consider what underused assets I have. The first one to spring to mind was that much like Leonard Cohen, I was born with the gift of a golden voice. A remarkably deep baritone, as it happens, which has done me well on various photoshoots and film sets. I was once so taken by what had just happened in front of the camera that I fell into a kind of silent rapture. One of the producers had to hiss furiously at me, “There are only two things you need to say on set, now for God’s sake say the second one!” before I came to my senses and shouted “CUT!”

The first time I’d hoped my voice could lead to a career was in my late teens when two school friends and I formed a band. I was the “singer”, and it was quickly apparent that while the speaking voice was good, it wasn’t remotely musical – I doubt even AI Autotune could have helped. We called ourselves The Introverts, very appropriate for a group that never went further than the rehearsal room, and our only legacy was a horribly embarrassing cassette tape that I hid deep in a drawer. Much later, I discovered my kid sister used to play it to her friends for cheap laughs when I wasn’t around.

Just after the banking crisis, I was asked to do a paid demo for a TV ad voice-over. The terribly suave ad director from London handed me the ad copy, directing me to sound as much like Richard Burton reading Dylan Thomas’s Under Milk Wood as possible. The text had no poetry to it, didn’t scan, and ended on an appalling tag line, but nevertheless I gave it a lash. A week later, I was greatly relieved to hear that they were “going in another direction”. I never found out what the full fee was, but I doubt it could have been enough to persuade me to have my distinctive tones going out over the airwaves on behalf of one of our most insolvent banks, urging the Irish public to “Be Brave”.

There’s one other use for my voice I’ve yet to try, and now that AI can easily clone them, it might be worthwhile seeing if mine can be licensed. A few years ago, a friend and I were chatting as we waited for a ferry from the Aran Islands. A tall, striking woman, who I later found out was the poet Rita Ann Higgins, marched over to us. Without any niceties or introductions whatsoever, she boomed “You have a fabulous voice!”. I murmured my thanks, and she continued “You should do phone sex – for money!”

AI now looms ever larger on the horizon, and my prospects for gainful employment remain … uncertain. Meaning that really, nothing much has changed, and at least I do know AI will have no real impact on the most important parts of my life. It’s incredibly fulfilling to make things by hand; a good dinner, the marks made with a pen on a page that became this article, and printed photographs that will be hung on walls rather than displayed for a few seconds on a screen. The machine might be able to output computer-generated, photo-realistic illustrations, but it can’t put on a play. With this in mind I’m now writing my first-ever one-act play as part of the dlr Lexicon playwriting course, which will receive a public outing in their theatre this June – yikes!

If you’re also worried about the irresistible rise of AI, take heart by creating whatever you can with your hands and even discover the joy of repairing something you might have otherwise thrown away. Not least because, if AI does take over the world and eat all the electricity, someday you may have to.

Despite the sleepless nights and unpaid bills, I’ll keep up my membership of the Precariat; something always turns up, usually at the last possible moment. And if someday it doesn’t, I’ll take comfort in an exchange I once had with the great writer Maeve Binchy, who’d worked alongside my father at The Irish Times. Many years later I was sent to photograph her for the Telegraph Magazine, and she remembered meeting me as an eight-year-old and asking that dreadful question which adults insist on asking of children: “What do you want to be when you grow up?” Apparently I replied, “a beach bum”. Fingers crossed, I’ll get there yet. @conorhorgan

READ MORE: Interview With A Man – John Molloy From Memo Perfumes