Catherine Heaney finds artist Anne Madden’s new works dazzlingly different …

The Irish Museum of Modern Art has just unveiled a landmark display of new works by one of the great Irish artists of her generation, painter Anne Madden. This vivid and visceral series of six oil paintings was made during the pandemic as the 91-year-old found herself, like so many others, suddenly housebound and alone. She turned to painting, but with no access to her studio she was forced to work in a completely new way, in a confined space and at the whim of the changing light as it moved across the walls of her Portobello home. She calls the process “very difficult” – but the results are dazzling.

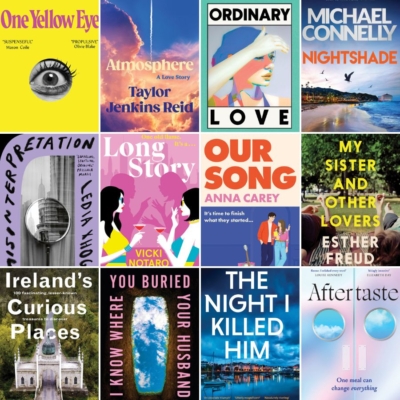

Metamorphosis. Leda and the Swan 2022-2023.

For any artist, adjusting to such challenges would have been hard, but for Madden, who has always worked on a large scale, it required a whole new approach. “I like doing paintings to my size,” she says (she has canvases custom-made to her own height). “I’ve always done paintings that are big. People say, ‘why so big? We can’t put them in our houses!’ – but I can’t do small things.” In her large studio, and throughout her career, she had worked with the canvases spread out on the floor, applying the paint from above. But now, working in her living room, they were taped to the wall, forcing a shift in perspective that she didn’t relish – “I can’t see them right,” she says.

Not that the constraints of their creation are apparent in the works that emerged: colour-saturated paintings of subjects that have long fascinated Madden – the classical figures of Antigone, Daphne and Ariadne, archetypes of transformation, female resilience and defiance. As Richard Kearney puts it in the catalogue essay, they represent “seven decades of art distilled into seven incandescent tableaux”. Yet for all that these are recurring themes in Madden’s work – cycles of nature, of life and death – the new paintings took her by surprise and consumed her lockdown days. “I was extremely busy here, and I was very glad that I had something in me wanting to get out. I didn’t know what they were about, even when I was doing them.” While Madden herself doesn’t offer easy explanations for the source of inspiration, it’s hard not see them as a response to the unsettling time in which they were made: the diptych of the tragic heroine Antigone burying her brother Polynices against the king’s command calls to mind the pandemic restrictions around funerals, and families denied the rituals around death and burial.

One of the most striking works in the new series is also unusual, even unique, in Madden’s oeuvre, in that it depicts the tragic death in childbirth of the teenager Ann Lovett in 1984, in a grotto under a statue of the Virgin Mary. The resulting painting is both tender and powerful – the nude young woman cradling her baby’s head. It’s striking that she should have chosen a contemporary and emotive subject, when her own lifetime has seen such seismic changes in the lives of Irish women. The painting came out of a conversation with a friend about Lovett’s story. “It had never occurred to me to do a painting about it – and suddenly it did, from this conversation. I could paint her.” Of the subject, she also adds, “It angers me, and of course I feel for her.” Like so many of her works, the painting thrums with Madden’s political and moral conviction, and so it seems fitting that she has donated such an important work to IMMA’s permanent collection.

“I’ve always done paintings that are big. People say, ‘Why so big? We can’t put them in our houses!’ – But I can’t do small things.”

Death of Ann Lovett (1968-1984)

The pandemic that gave rise to these paintings and the solitary existence it enforced was a far cry from the life Madden led with her late husband, renowned artist Louis le Brocquy. The two married in 1958 and lived in the south of France, where they shared a studio and raised two sons, Alexis and Pierre. They returned to Ireland often and also kept a small studio in Paris, where they were part of an international scene in the 1960s that included artists from around the world. In the 1990s, they moved back to Dublin and into the handsome redbrick house where Madden still lives today. Tales from these times are woven through her conversation – matter-of-fact recollections of the artistic and literary giants who were part of her and Louis’ life. Discussing her painting technique prompts a story about one such friend: “A funny thing about Francis – Francis Bacon. It was in Paris at an exhibition of my work, and he said to me, pointing at a painting, ‘How did you do that?’ I said, ‘I did it on the floor. I threw it in one go on to the canvas on the floor.’ And he said ‘Oh. I couldn’t do that on my floor … – because it was so filthy!” Later, she tenderly recalls her and Louis’ final visit to their friend Samuel Beckett, shortly before his death: “He knew it was the last time, and we knew it was the last time.”

Madden is a living link to these monumental figures from the past, she herself holds a crucial place in that chain of artistic inheritance for younger generations of Irish artists. Here she is, in her 90s, producing vital new work. When I ask how she feels about coming to the end of a cycle of work and sending it out into the world, she is unsentimental: “You leave things – you’ve got to let them live their own life, really.” And with that, she gets back to work.

Anne Madden: Seven Paintings is at the Irish Museum of Modern Art, Royal Hospital Kilmainham, Dublin, until 21 January 2024; www.imma.ie.