In this extract from The Gourmand’s Lemon, the role of lemons in literature is explored…

Lemons crop up often in the literary diet. In Kansas, Beat writer William S Burroughs had fresh-squeezed lemonade with his morning methadone before getting down to the business of feeding his wiry clowder of cats. Playwright Tennessee Williams was a dedicated gourmet who taught himself to cook in retaliation to his mother’s “uncanny ability to make tinned soup taste like dishwasher detergent”, and his favourite dessert was a Girl Scout recipe for lemon icebox pie.

Poet Maya Angelou believed cooking was another means of communication; she loved her grandmother’s “unimaginably good” lemon meringue pie, a dish that would make “a rabbit hug a hound” and “a preacher lay his Bible down”. Sylvia Plath’s journals are filled with grocery lists and recipes for kitchen creations that acted as a form of therapy for the troubled writer. She composed one of her most famous poems, “Lady Lazarus”, with its pitch-dark meditation on suicide, while baking a sunny lemon pudding cake. And gonzo journalist Hunter S Thompson’s extravagant breakfast ritual, enjoyed “outside, in the warmth of a hot sun, and preferably stone naked”, insisted upon “a chopped lemon for random seasoning” to accompany “four Bloody Marys, two grapefruits, a pot of coffee, Rangoon crepes, a half-pound of either sausage, bacon, or corned beef-hash with diced chillies, a Spanish omelette or eggs Benedict, a quart of milk … and something like a slice of Key lime pie, two margaritas, and six lines of the best cocaine for dessert”.

Lemons have been associated with a certain excess in some novels. F Scott Fitzgerald’s cautionary Jazz Age tale The Great Gatsby (1925) describes crates of lemons arriving at the doomed titular character’s mansion on Long Island every Friday, from a New York fruiterer. They end up “in a pyramid of pulpless halves” on Monday mornings, the squeezed-out leftovers of Gatsby’s decadent weekend-long cocktail parties. In Tom Wolfe’s merciless satire of 1980s greed, The Bonfire of the Vanities (1987), New York’s “lemon tarts” aren’t edible, they’re vicious caricatures: “Women in their 20s or early 30s, mostly blondes (the Lemon in the Tarts), who were the second, third, or fourth wives or live-in girlfriends of men over 40 or 50 or 60 (or 70), the sort of women men refer to, quite without thinking, as girls.” These so-called Lemon Tarts replace skeletal elder wives – the lettuce-eating “social x-rays” – in Wolfe’s cutthroat universe.

Joan Didion saw something deeply ominous in California’s lemons. Her essay “Some Dreamers of the Golden Dream” (1966) details a grisly true-life murder: in 1964, San Bernardino resident Lucille Miller burned her husband alive in their Volkswagen, having pushed it into a lemon grove. The plan was to collect the double-indemnity insurance – Miller’s route to the lifestyle promised to her by Hollywood. On an unremarkable plot of subdivisions, “where there are always tricycles and revolving credit and dreams about bigger houses, better streets”, the dense foliage of the lemon groves is “too lush, unsettlingly glossy, the greenery of nightmare …”. In the author’s equally discomfiting Hollywood-set novel Play It as It Lays (1970), lemons are plastic and lemon juice artificial, an LA masseur who aspires to be a writer complains, in a town with a shiny surface that is ultimately empty of true value.

Whatever potent feelings might be brought on by citrus are taken to supernatural heights in Aimee Bender’s The Particular Sadness of Lemon Cake (2010), the story of a nine-year-old girl who gains the ability to taste the emotions of a person via the food they cook. Cookies taste of “tight anger”, sandwiches shout “love me” and roast beef is adultery flavoured. As for her mother’s lemon cake, it tastes of “absence, hunger, spiralling, hollows”. It’s a mournful side of the fruit that was voiced in the twelfth century, when Sicilian-Arabic poet Abd ar-Rahman described lemons “like the pale faces of lovers who have spent the night crying”. Master of minimalist storytelling Raymond Carver also found sadness in citrus in his 1989 prose poem “Lemonade”. A brief snapshot of a father whose son drowns after going to retrieve a thermos of lemonade, the tragedy leads to a tirade against the fruit.

And yet for some authors lemons have been a symbol of hope. Sandy Tolan’s The Lemon Tree (2006) details a friendship between an Israeli woman and a Palestinian man that lasts over 35 conflict-strewn years, after springing up in the garden of the house each called home. Two of the longest literary masterworks in history have given the citrus a pivotal role.

Traditionally made with lemon zest, the scallop-shaped cake known as a madeleine was the trigger for seven volumes of Marcel Proust’s opus, In Search of Lost Time (1913), after its narrator takes a bite and is transported into the past. And on June 16 1904, the hero of James Joyce’s Ulysses (1920), Leopold Bloom, visits Sweny’s pharmacy in Dublin and spends four pence on a bar of soap that smells of “sweet lemony wax”, an item that has become somewhat talismanic for Joyce aficionados. The “coolwrappered soap” accompanies Bloom, shifting from pocket to pocket, on his Dublin Bloomsday odyssey, even becoming a character in its own right. “We’re a capital couple are Bloom and I; He brightens the earth, I polish the sky,” says the soap. The only intact Victorian shop interior left in Dublin, Sweny’s is a dedicated Joycean sanctuary, and it’s the brisk sales of lemon soap that keep the space open as a living monument to literary endeavour.

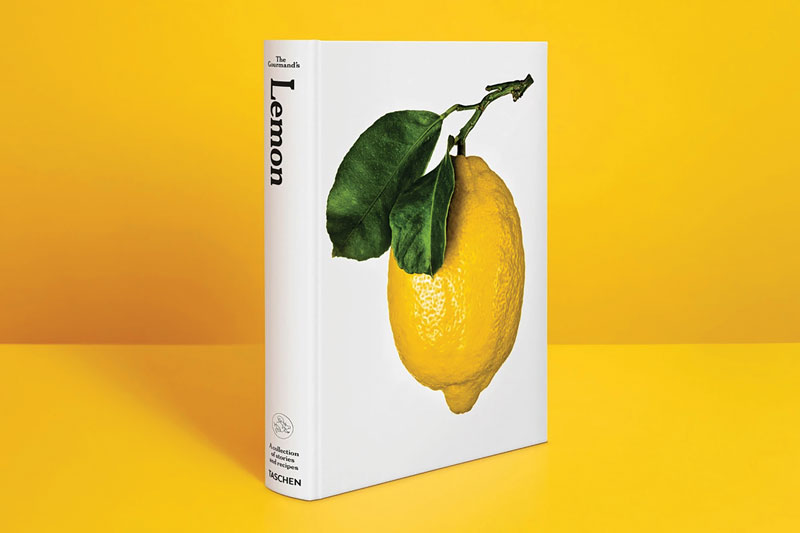

The Gourmand’s Lemon, A Collection of Stories and Recipes, Taschen, €46, is out now.