Telling the truth amidst devastation was a gruelling job but these trailblazers made it their life’s work …

As the war in Ukraine grinds on and veteran correspondents, Lindsey Hilsum, Lyse Doucet, Clarissa Ward and our own Orla Guerin report from its ravaged cities, we are struck by their courage under literal fire and their ability to remain calm amongst chaos. These women bear unflinching witness to death and destruction, delivering reports in measured tones that betray little of the danger they face. That both Lindsey Hilsum (International Editor for Channel 4) and Lyse Doucet (BBC Chief International Correspondent) are both 63, inspires even greater admiration.

The death of reporters, Oleksandra Kuvshinova and Oksana Baulina in Ukraine has also highlighted the danger faced by female journalists on the frontline. The death of Marie Colvin in 2012 in Syria was a stark reminder that gender does not protect during war: female journalists can become “collateral damage” like any civilian. Reporting wars is not for the faint-hearted. As Janine Di Giovanni observed, “War does something to your head, something irrevocable.” Violence and vengeance take their toll and war correspondents can suffer PTSD, depression and anxiety as a legacy of their work. Getting out alive is one thing, staying sane in the aftermath of a career at war, another thing utterly.

Pictured: Correspondent Orla Guerin in Ukraine

Hilsum and her contemporaries are not the first women to report from war zones. They have assumed the mantle from a coterie of pioneering journalists who broke down rigid barriers in World War Two (WWII) to infiltrate what was previously an insular boy’s club where women were not welcome. Today’s Sky, CNN and BBC female correspondents owe a debt to a group of exceptional trailblazers: Clare Hollingworth, Marguerite Higgins, Lee Miller and Martha Gellhorn, who had to fight, cajole and sometimes deceive to be allowed to cover warfare.

Clare Hollingworth, an English novice reporter who trumped male contemporaries with her 1939 “scoop of the century” in The Telegraph, about the “1000 tanks massed on the Polish border”, may have been the first woman journalist in a war zone. Her report preceded the invasion of Poland which launched WWII and alerted the British Foreign Office to Germany’s intentions. Prior to journalism, Hollingworth had been an aid worker. WWII was transformative for her: she covered the North Africa campaign despite being denied accreditation because of her sex. Undeterred she still attended press conferences and briefings and ventured behind enemy lines despite clashing with General Bernard Montgomery.

Pictured: veteran war correspondent Claire Hollingworth

During a long and pioneering career, Hollingworth reported in Algeria, Vietnam and China. John Simpson said of her that she was “in the right place at the right time” – a prerequisite for successful reportage. She lived until 105 after narrowly escaping death in 1946 when a bomb blast destroyed the King David Hotel in Jerusalem. She proved that being female was no obstacle to the role of war reporter and asserted: “I would never use my femininity to get a story a man could not get.” Until her death, she always kept her shoes by her bed, a legacy of her training to always be ready to leave in a hurry in war zones.

Marguerite Higgins (pictured above), an Irish American reporter who covered WWII (in London, Paris and Germany), the Korean War, and the Vietnam War used every opportunity to get a story and is often called the first female American war correspondent. Unlike Hollingworth, she was not beyond using her charm and beauty to get interviews. She was extremely competitive and determined: she had to be. In those days women had to be tough to succeed in journalism as men dominated a largely chauvinistic industry. Higgins had a long career with the New York Herald Tribune and was also a columnist with Newsday. She was the first woman to win a Pulitzer Prize for Foreign Correspondence in 1951 (when she was cited for her “enterprise and courage” for her reporting in Korea). She also witnessed the liberation of Buchenwald and Dachau concentration camps and covered the Nuremberg war trials.

Higgins experienced bitterness from male colleagues who bitched about her sleeping around to get stories, but her reporting in Korea made her a national figure. Undeterred by malicious gossip, she combatted enormous odds to succeed and used all her resources to steal a march on male correspondents. When she featured in a Life Magazine profile in 1951, she was patronisingly labelled a “Girl War Correspondent” (see above) despite displaying exceptional bravery in Korea, notably helping to give blood plasma to wounded soldiers while under persistent fire. Her work proved that women could be equally as courageous and focused as men in a war zone.

She died prematurely aged only 45 of the parasitic disease, Leishmaniasis which she contracted in Vietnam in 1965, conscientiously filing copy right up until her death. Her obituary in the New York Times said: “Marguerite Higgins got stories other reporters didn’t get. She did it with a combination of masculine drive, feminine wiles and professional pride. She had brass and she had charm and she used them to rise to the top of a profession that usually relegates women to the soft beats of cooking, clothes and society.”

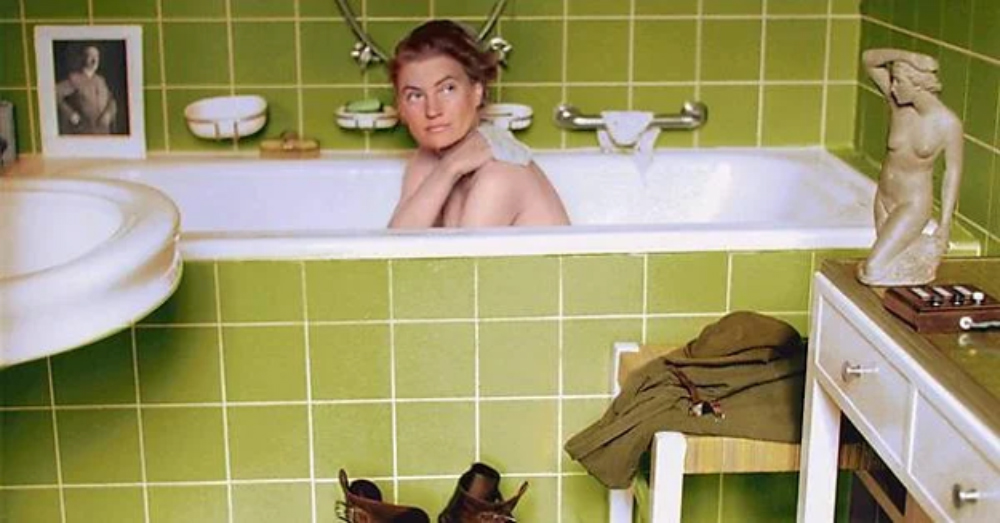

Pictured: Vogue cover girl and war correspondent Lee Miller

Lee Miller, who did start her career in the soft world of clothes and society, might superficially appear to be the most unlikely candidate to become a war correspondent, but it was a role at which she excelled. Miller was the 1920’s Vogue cover girl shot by Steichen, Horst and Hoyningen-Huene who became the lover and collaborator of Surrealist photographer, Man Ray and later an accredited US war correspondent covering the siege of St Malo and the liberation of Paris. Her stark photos of Dachau and Buchenwald shocked humanity and still retain their shocking potency.

Under the inspired editorship of Audrey Withers of British Vogue, Miller evolved from shooting fashion at the Vogue studio in London to recording scenes of the Blitz, to finally embedding with the US troops as they liberated Europe. It was Withers who perceived Miller’s “strong journalistic sense” and gave her the opportunity to develop into an exceptional photo-journalist, who not only shot the war, but also wrote about it in unflinching prose. Miller did not find writing easy; she once said “Every word I write is as difficult as ‘tears wrung from stone’.” Withers who identified the photographer’s “gift for extraordinarily fresh and vivid writing” was pioneering to feature war reportage in a fashion magazine and was central to Miller’s success.

Ironically, the most iconic image associated with Lee was not shot by her, but by her lover, Dave Scherman. It shows her in the Fuhrer’s bath, in Hitler’s Munich apartment, on the very day he committed suicide and she had witnessed the liberation of Dachau. When she sent her images of Buchenwald to Vogue, Miller sent an accompanying plea, “I implore you to believe that this is true.” Vivid as these harrowing images of Buchenwald remain, Miller’s written description of the camp equally seethes with anger and nausea. For 18 months, high on adrenaline Miller saw horrifying suffering which undoubtedly prompted the drinking that marked her later life. The war was her finest hour and her photojournalism remains a trailblazing record of the total destruction of the Nazi regime, but it was achieved at immense personal cost to her physical and mental health.

Miller found the readjustment to civilian life intensely difficult; restless and distressed by the war yet bored by civilian life, she sought solace in alcohol. After the war, she married Roland Penrose, had a son and moved to the English countryside. As the years went by, she abandoned photography and down-played her career. Her archive languished in her home and in Vogue HQ until it was re-discovered by her son, Anthony Penrose after her death. A new film Lee (with Kate Winslet as Miller, due to begin filming this year), will hopefully raise awareness of her immense contribution to photojournalism.

Pictured: novelist, travel writer and war correspondent Martha Gelhorn

Martha Gellhorn, the final member of this revolutionary group was the last to retire, reporting on her last conflict, the US invasion of Panama in 1989, aged 81. As well as being one of the greatest war correspondents of the 20th century, she was also a novelist and travel writer. She married Ernest Hemmingway after they came together reporting Spain’s civil war. They divorced five years later when Hemmingway became exasperated by her absences and jealous of her success. Gellhorn spent a lifetime trying to extricate herself from Hemmingway’s overbearing shadow, stating: “I’ve been a writer over 40 years. I was a writer before I met him and I was a writer after I left him. Why should I be a footnote in his life?”

During her WWII career she reported on the rise of Hitler, the Russian invasion of Helsinki, the liberation of Dachau and the D Day campaign (being the only woman to land in Normandy that day) when she inveigled her way onto a hospital warship to report first-hand accounts from wounded soldiers. She also covered the conflict in Honk Kong, Burma, Singapore and England, recalling later, “I followed the war wherever I could reach it.” She adopted a son, Sandy in war-ravaged Italy but frequently left him, to report on stories including the Arab-Israeli conflict and wars in Central America, Africa and Vietnam. Despite her career, Gellhorn cared deeply about her personal appearance: she loved expensive shoes and was vain, rigidly monitoring her weight.

Pictured: Martha Gelhorn with then-husband Ernest Hemmingway

Ill with ovarian cancer that had spread to her liver and almost blind from an unsuccessful cataract operation, she committed apparent suicide in London in 1998. During her 60 year career she had reported on almost every major world conflict and this fidelity to the story was the most enduring relationship of her life. Fuelled by anger and a sense of injustice that didn’t dim with age, she simply kept working until she couldn’t. Telling the truth amidst devastation was a gruelling job but these trailblazers made it their life’s work and in doing so created the blueprint for the women war correspondents now on every frontline. Brave and compassionate – they illuminated the human cost of war and left an enduring record of war experienced first-hand. Their initiative, tenacity and perseverance created the role of the modern female war reporter. In documenting humanity’s worst traits, they revealed their best.

Follow Rose Mary on Twitter @RoseMaryRoche

LOVETHEGLOSS.IE?

Sign up to our MAILING LIST now for a roundup of the latest fashion, beauty, interiors and entertaining news from THE GLOSS MAGAZINE’s daily dispatches.