On family, roots, writing and success …

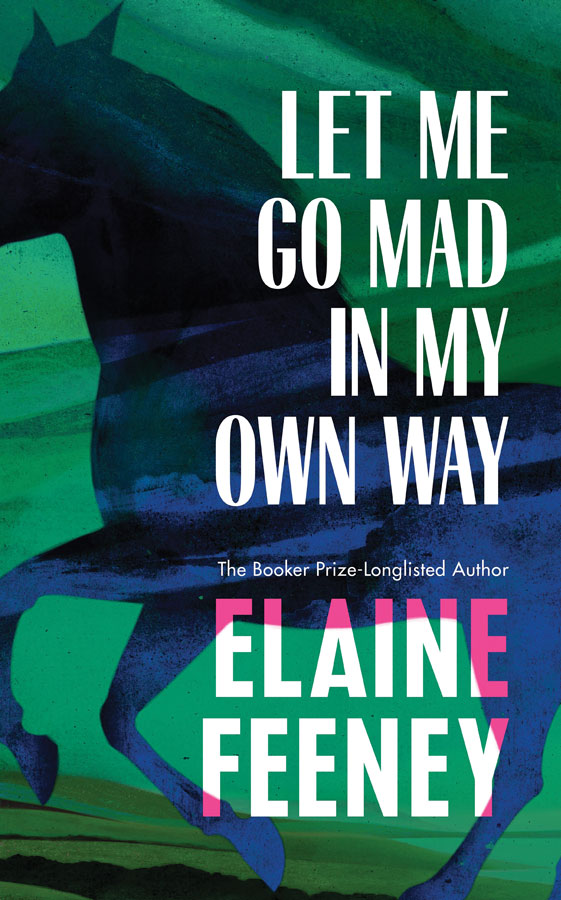

Elaine Feeney is a writer and lecturer at the University of Galway. She has published three poetry collections and her debut novel, As You Were, won Dalkey Book Festival’s Emerging Writer Prize, The Kate O’Brien Prize and The Society of Authors’ McKitterick Prize. Her second novel, How to Build a Boat, was nominated for The Booker Prize and named Best Fiction 2023 by The New Yorker.

ON HOME I live in a 1970s bungalow, in Athenry, Co Galway, the house I’ve lived in all my life – I bought it when my parents moved on. It’s in the countryside, surrounded by green fields. This is where I grew up, and it’s also where my grandparents and great-grandparents lived – just down the road, “under the bridge”. These people oft en come up in my writing – the stories they told me, the place itself, and especially the local landscape, which features in my latest novel, the fi rst I’ve set in Athenry. Whether I chose it consciously or not, it’s part of who I am, and something about it keeps me here.

ON FAMILY John McGahern once said, “the whole country is made up of families, and each family is a kind of republic”. That rings true for me. Like all families, mine is full of its own dynamics. I’m married to a man from Wexford – he’s a great person, though he wouldn’t want me to say that – and we have two sons and a one-eyed cat. My mother and sister live nearby, which is lovely. I have five siblings, and lots of nieces and nephews. We’re a chatty family, big readers, and mostly on the same page politically, which is a relief. I often think about how hard it must be in families where people don’t share the same basic values.

ON ROOTS I like to explore how the past and present connect and shape us. I remember my grandparents well. They were good storytellers and great talkers, and they passed on a lot through conversation. But one of my grandfathers, a farmer, was quieter. I used to make up stories in my head about what his life was like as a boy, because he rarely spoke about it. In my writing, I’ve tried to fi ll in those gaps with fi ction. Maybe he was just naturally quiet, but I’ve always wondered what he chose not to say, and why.

“I got a Petit 990 typewriter for Christmas when I was about eight or nine, and started typing what I thought were very serious political pieces that I could maybe read on the news.”

ON WRITING I’ve loved writing since I was a child. I got a Petit 990 typewriter for Christmas when I was about eight or nine, and started typing what I thought were very serious political pieces that I could maybe read on the news. Looking back, they were full of hopeful ideas about peace and understanding, the naiveté of childhood.

ON MY DESK My desk is a bit of a mess most of the time. It’s where I work, but also where laundry piles up and books gather. I usually have my laptop there, along with a few notebooks – one for the draft I’m writing, and another for trying to fi gure out what it’s really about, though a student once told me this kind of self-analysis of my art isn’t cool – that you shouldn’t try to explain your own work, like David Lynch. Maybe they’re right.

ON SUCCESS Success is a hard thing to define these days. For me, it’s about being able to speak freely, and having the chance to do that through writing. I feel very lucky to be able to.

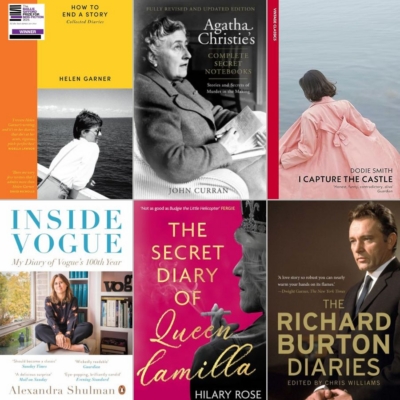

ON BOOKSHOPS As a child, I spent many Saturdays in the Athenry library with my brothers and sister. Libraries and bookshops have always felt like important places to me – quiet, open, and full of possibilities. I’ve met some wonderful booksellers over the years, and their enthusiasm has meant a lot.

Let Me Go Mad in My Own Way (Harvill Secker, €16.99) is out now.