On living in a castle, rewilding, family and more …

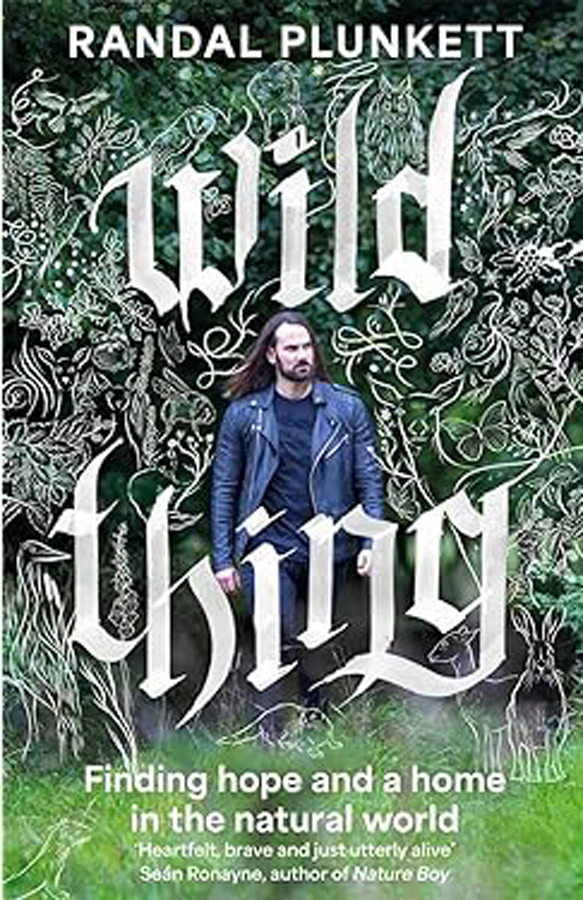

Randal Plunkett’s book, Wild Thing: Finding a Home and Hope in the Natural World, tells how he rewilded the ancestral estate in Dunsany Castle, where he lives with his wife and daughter.

How would you describe your parents? Honourable, thoughtful, the best I could have. We were asset rich, liquid poor, because the monies that my parents would make would be spent completely on the Castle. We lived very simply, we didn’t have flash cars, the house was freezing all the time. My father was more of an artist, so he was softer, but my mother was basically a bulldozer. There was very little respect in my house for people who didn’t work hard.

How do you see your parents’ influence in your later life? As much as I resisted – and I resisted a lot – I think I’ve become my parents. My father died in 2011, before I was ready, and he went to his grave not knowing if he’d given me what I needed to take on [the title and Dunsany]. It’s a rite of passage in my family, that we never know if the next generation is going to take on board the lessons of the past. Every family has that, but in mine, the costs are much higher in terms of what happens if someone doesn’t toe the line.

You write about your dread of becoming Lord Dunsany. When did that start? My parents loved me but they didn’t cushion anything. From the moment I can remember I was being prepped. I went to Ludgrove [boarding school in Middlesex] with Prince William and Prince Harry and I can relate a little bit to what they dealt with because they were born a certain way. Their situation is very extreme but it’s not that different either.

Did school make a big impact on your life? I went to Ludgrove when I was eight or nine and it was a really hardcore boarding school. Then I boarded in Headfort and I briefly stopped boarding when I went to King’s Hospital. I wasn’t an easy kid and it took a few goes to find the right place. I ended up in a swanky school in Switzerland called Le Rosey. It’s one of those super-elite lizard-people schools. Even with the privilege I had, I was considered a pauper.

Have you ever seen two twelve-year-olds with Rolexes fighting over whose watch cost more? That’s really something. Did I like it? I loved it!

When did you come around to the idea of inheriting the title and estate? When my dad got sick, we put our lives on hold to look after him. The last day I spoke to him, I promised that I would look after my mother and I would not make him ashamed of me. That’s when I said to myself, “I will fake it if I have to, but I won’t be the one who destroys everything.” Many times, I almost went back on my commitment to this place, but ultimately I always toe the line.

Did you fear at all that commitment to the estate would leave no space for your creative endeavours? That I knew for certain and I struggled with it. It’s only in the last few years, since my mother passed away, that I’ve started to develop my creative career. It’s the first time in a very long time where I’m not looking after a sick parent.

How proud are you that it’s the largest privately owned nature reserve in Ireland? I walked into this completely blind and everybody thought I was a fool, and I’m sure they were right. I knew nothing about rewilding, because I was never into the country at all. When I was young, I never even went outside. When my mother was sick, I began to get out of the house to give myself room to breathe and gradually, the allure of nature began to take hold. I began being curious, then I began to love it, and now I feel committed to it.

Is being a ‘metalhead’ an important part of your identity? When I was a child and then a teenager, everyone said it was just a phase, but I’m 42 now and it hasn’t passed. I still have the same clothes and I still like death metal. I suppose I look like an adolescent in an older person’s body, but I’m not going to change and I don’t apologise for it.

How do you think people regard you? One of the perks of living in a castle is that you’re allowed to be eccentric. I lean into that. I have no problem with it.

Does it bother you that your daughter can’t inherit the title? It doesn’t really matter, because titles are nonsense anyway. I don’t consider myself to be anything. I’m a mister. That’s what I have in my passport. The only thing that would make me sad is the fact that she wouldn’t be allowed because of her gender.

I look like a cliché – ‘guy who works in bookshop’.

What are your favourite shoes? I have the most luxurious slippers from Dunnes that I stole from my wife. They are basically amazing fluffy socks with a sole on them. In a cold house, a pair of cosy socks is a luxury.

Do you have an exercise routine? It used to include lots. Nowadays, if I can get out of bed without my back hurting, it’s a good start. But for exercise, I’m a weight-lifter and a walker.

You most recently read … Leo Varadkar’s autobiography. I arrived at King’s Hospital in his last year there. We did not know each other.

You most recently listened to … I listen to books and music. I’m in the middle of listening to a book called Alchemy by Rory Sutherland.

What’s a holiday you’d like to repeat? What’s a holiday?

What do you cook at home? All vegan, so a lot of beans, chickpeas, tofu. I’m partial to a bit of vegan chicken. I like to say we’re very healthy, because we eat lots of plants, but I also like junk food.

What would your perfect weekend involve? Sending the family away so it’s just me and all my Jack Russells for a death-metal listening party with lots of vegan junk food.

Wild Thing: Finding Hope And A Home In The Natural World by Randal Plunkett (Bonnier Books) is out now. For rewilding tours, email dunsanynaturereserve@gmail.com.

SEE MORE: Seán Ronayne On Birdsong And Autism