Our survival as individuals and as a society depends on bravery …

Courage is for me one of the greatest virtues, up there at the top with love and charity. Courage is a miracle, because it is contrary to the survival instinct which tells us to keep safe and seek protection. Courage requires us to take risks. It can endanger your peace of mind, relationships, career and, in extreme cases, your life.

In more than 40 years of journalism, I have often witnessed courage – and its mirror opposite, cowardice – in politics, business and daily life. It is most obvious in war, which brings out the best and worst in people.

The second World War still feels very present in Paris, where I live. Through four years of Nazi occupation, most French people just tried to get on with their lives. When liberation was imminent, thousands became “des résistants de la dernière heure” – last-minute members of the Resistance. Only a tiny percentage had the courage to resist occupation in the darkest hours.

I ask myself, “What would I have done?” I want to believe that I would have had the courage to join the Resistance. We cannot know until we are tested. The question was hypothetical for most of our lives. It is less hypothetical now. We are entering an era where courage is required of private citizens, most obviously in the US but also across Europe.

The courage of Ukrainians has preserved their country as a sovereign nation.

Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine has reminded us of the power of courage as a force in world politics. When the US and UK offered to spirit President Volodymyr Zelenskiy out of his country on the morning of February 24, 2022, he replied, “I need ammunition, not a ride.”

It was widely predicted that Russia would seize Kyiv within days. Russia is the world’s biggest country, with a land mass about 28 times the size of Ukraine. Yet nearly four years later, the world’s fifth largest army has not been able to defeat a former colony whose population is less than one third of Russia’s, whose economy is less than one tenth of Russia’s.

Fear too is a powerful force in politics, which Vladimir Putin exploits to the fullest, flaunting his nuclear weapons to limit western help for Ukraine. Zelenskiy told The Economist in 2024: “Putin feels weakness like an animal because he is an animal. He senses blood, he senses his strength. And he will eat you for dinner with all your EU, NATO, freedom and democracy.”

In August 2023, I was in Kyiv, reporting a story for The Irish Times about women in the Ukrainian armed forces. The women’s soldiers’ group Veteranka put me in touch with a half dozen women in the military.

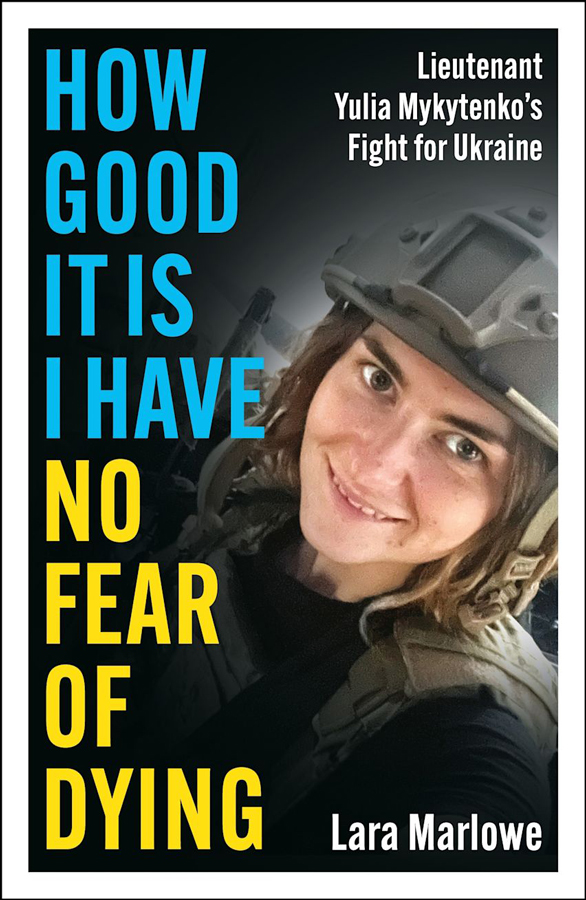

Among them was Lieutenant Yulia Mykytenko, then 28 years old and the commander of a drone reconnaissance platoon on the front line. She had joined the army in 2016, on graduating from university.

Remember that the war started in 2014, with Russia’s seizure of Crimea and much of Donbas. Lt Mykytenko’s husband, Illia Serbin, also a soldier, was killed in a Russian artillery bombardment on the eastern front in 2018. Her father, Mykola, a master sergeant in Ukraine’s National Guard and an activist in the No Capitulation movement of army veterans, self-immolated in 2020 to protest what he saw as the abandonment of Ukraine’s independence.

Lara Marlowe and Yulia Mykytenko, Howth, Co Dublin, October 2024. Photograph by Dara MacDonall.

Soon after I interviewed Yulia, I returned to Paris. But thoughts of that courageous young woman stayed with me. I wrote to ask if I could write a book about her. Life on the front line is exhausting, and Yulia wasn’t really interested. But she eventually accepted because, she told me later, the Russians are very good at propaganda and it’s important that Ukrainians tell their side of the story.

I remain awestruck by Yulia’s courage, which is to me emblematic of the courage of a people. Never have I come to know so much about an interviewee. Yulia jokes that I remember her life better than she does. It’s been a hard slog because she is a private person and never boasts about her exploits. She minimised the importance of the medal she received from President Zelenskiy in December 2022 for – and I quote the citation – “individual courage and heroism while rescuing people … endangering one’s own life.”

While Yulia and I were working on the book, the French writer François Sureau delivered a speech on the theme of courage to the Académie Française. This passage from the conclusion of his speech reminded me of Yulia: “At the beginning of these adventures, there is solitude, darkness, the impossibility of foreseeing the consequences for oneself and for others. Courage is a leap into the unknown, taken by the light of a dark lantern. There are no more prophets, no dogmas, no signs to show the way, only the example of those who have preceded us on an endless path, in a peregrination that expresses the best of what we are.”

A campaign by Lt Mykytenko and her sisters-in-arms in Veteranka gained the right for Ukrainian women to hold combat positions. “War has no gender” was their slogan. Women constitute less than one per cent of today’s Ukrainian armed forces but they’ve had the courage to confront deeply ingrained sexism in the military.

“Never show weakness,” is Yulia’s mantra. When she was promoted to lead a reconnaissance platoon at age 22, 16 of 20 men transferred out of the unit rather than be commanded by a young woman. The following year, a lieutenant colonel tried to humiliate Yulia when she requested leave time for exhausted soldiers. “You just need a man,” the officer said snidely. Yulia had recently lost her husband, but she maintained her composure and told the lieutenant colonel that was the most disgusting, sexist remark she had ever heard.

Courage has a cost. Yulia has lost more than 20 close comrades and says she no longer feels emotion.

As Yeats wrote, “Too long a sacrifice/Can make a stone of the heart.” Her mother, Tamara, a psychotherapist, posted a text on social media this autumn. It helped me understand why Yulia sometimes seems distant.

Tamara felt puzzled and hurt by the change in her daughter. She eventually realized that “the nervous system takes longer to return home than the backpack does; the front and the rear don’t merge in 15 minutes. Out there she lived in constant threat mode; hypervigilance doesn’t switch off on command. The brain gets used to scanning the surroundings every second – where’s the exit, who just came in, where’s that noise coming from … Stress hormones are still in the blood, sleep is broken, so any sudden sound or touch registers as danger. These are survival skills …”

Tamara has developed what she calls her “safety protocol” for Yulia’s visits: “Before I hug her, I ask, ‘Can I give you a hug?’ … I don’t approach from behind or touch unexpectedly. I avoid sudden movements … Before inviting guests, I ask if she has the energy for people … I cry only when I see the tail of the train taking her back to the war. At home, I remove loud noises … I don’t turn on the news without her consent. I don’t scold her for being on the phone; we agree on short ‘offline windows’, ten or 15 minutes just for us … Why does it work? The nervous system reads: ‘the space is under control; a loved one is near. It’s safe to let go of hypervigilance’.”

Consider the difficulty that Yulia has readjusting to civilian life and the care that Tamara takes to help her. Multiply that hundreds of thousands of times and you have an idea of the scale of the cost of courage. The mental and emotional turmoil caused by war continues long after.

Just as Tamara Mykytenko has devised ways to ease her warrior daughter’s brief stays in civilian surroundings, we find ways to boost our courage in daily life. If I was nervous about an interview or a speaking engagement, I used to tell myself, “I’ve been bombed in Baghdad; this is nothing.” Self-persuasion and self-preparation bolster one’s courage for any undertaking, be it in business, journalism or war. I believe in good luck charms and talismans. In civilian life, I’ve found that nothing boosts selfconfidence like wearing a new outfit.

When I’ve covered wars, I played other mind games, like telling myself that more people survive than are killed or wounded. My late former husband, the war correspondent Robert Fisk, used to tell me, “Don’t be so vain as to think the artillery shell is looking for you.” Robert, who died five years ago, had immense physical courage, but more importantly, he had the moral courage to tell the truth about what happened in the Middle East.

We must find the courage to stand up for those less fortunate than ourselves, for our own rights and for what is right, full stop.

Two brave female colleagues, Marie Colvin of the Sunday Times and Shireen Abu Akleh of Al Jazeera television, were killed reporting from war zones. Bashar al-Assad’s regime targeted Marie and photographer Rémi Ochlik with an artillery strike in 2012. Shireen was shot dead by Israeli soldiers while reporting from the West Bank in 2022. Reporters Without Borders says Israel’s armed forces have killed 220 journalists since October 7, 2023, making Gaza the deadliest war ever for journalists. I salute their courage.

The world never learned the identity of “Tank Man”, who stopped a column of Chinese tanks on Tiananmen Square on June 5, 1989. The protests were crushed, but the courage of “Tank Man” entered the world’s collective conscience. Several Ukrainians similarly blocked columns of Russian armour at the beginning of the full-scale invasion. On October 21 this year, a protestor in Manhattan known only as “polka-dot dress woman” planted herself in front of an armoured police vehicle to hinder an ICE raid deporting migrants.

Whistle-blowers have shown extraordinary courage, risking their careers and sometimes their lives to reveal, for example, the truth about the Vietnam War, the Israeli nuclear programme and the extent of torture in Syria. This summer, US tech employees were fired or resigned after denouncing the use of Microsoft technology by the Israel Defence Forces for the mass surveillance of Palestinians.

As Donald Trump attempts to bend the world to his will, values which were never questioned in our lifetime are challenged daily. When the provincial government of Ontario broadcast archive clips of Ronald Reagan criticising tariffs, Trump stopped trade negotiations with Canada. The president of Colombia denounced deadly US strikes on boats in the Caribbean; Trump called him a “drug dealer” and cut off aid to Colombia. Charles Kushner, Trump’s ambassador to Paris, said French companies who advocate Diversity, Equity and Inclusion will be shut out of US markets. Members of Congress have threatened to ban Irish imports and pull US companies out of Ireland because of Irish support for Palestine.

“Noli timere” – don’t be afraid – were the last words of Seamus Heaney, in a text to his wife Marie on August 30, 2013. One doesn’t have to look far to find things to be afraid of. There are 61 wars being waged in the world today, a record since 1946, according to the UN. Global warming affects our lives and Trump’s tariffs wreak havoc in international trade. Most frightening to me, a tide of populist, extremist, far-right election victories threaten democracy as we’ve known it. If you think it can’t happen in Ireland, read Paul Lynch’s Booker Prize-winning Prophet Song, with its credible portrayal of Ireland sliding into totalitarianism.

Courage means the willingness to speak up and act, to take risks, including financial and economic. We must find the courage to stand up for those less fortunate than ourselves, for our own rights and for what is right, full stop. Our survival as individuals and as a society depends on it.

How Good It Is I Have No Fear of Dying: Lieutenant Yulia Mykytenko’s Fight For Ukraine, is out now.