Our emotions really get a bad rap. They are accused of blurring our decision-making, affecting our memory, playing a significant role in our mistakes, and preventing our learning. If the emotions have so much power over us, we need to know what … they are, exactly. In Part One of Thinker’s Corner, Daisy Hickey investigates how philosophers define emotions …

Classical philosophers said that ‘emotions are stand-alone sensory experiences’ – in other words, useless sensations…

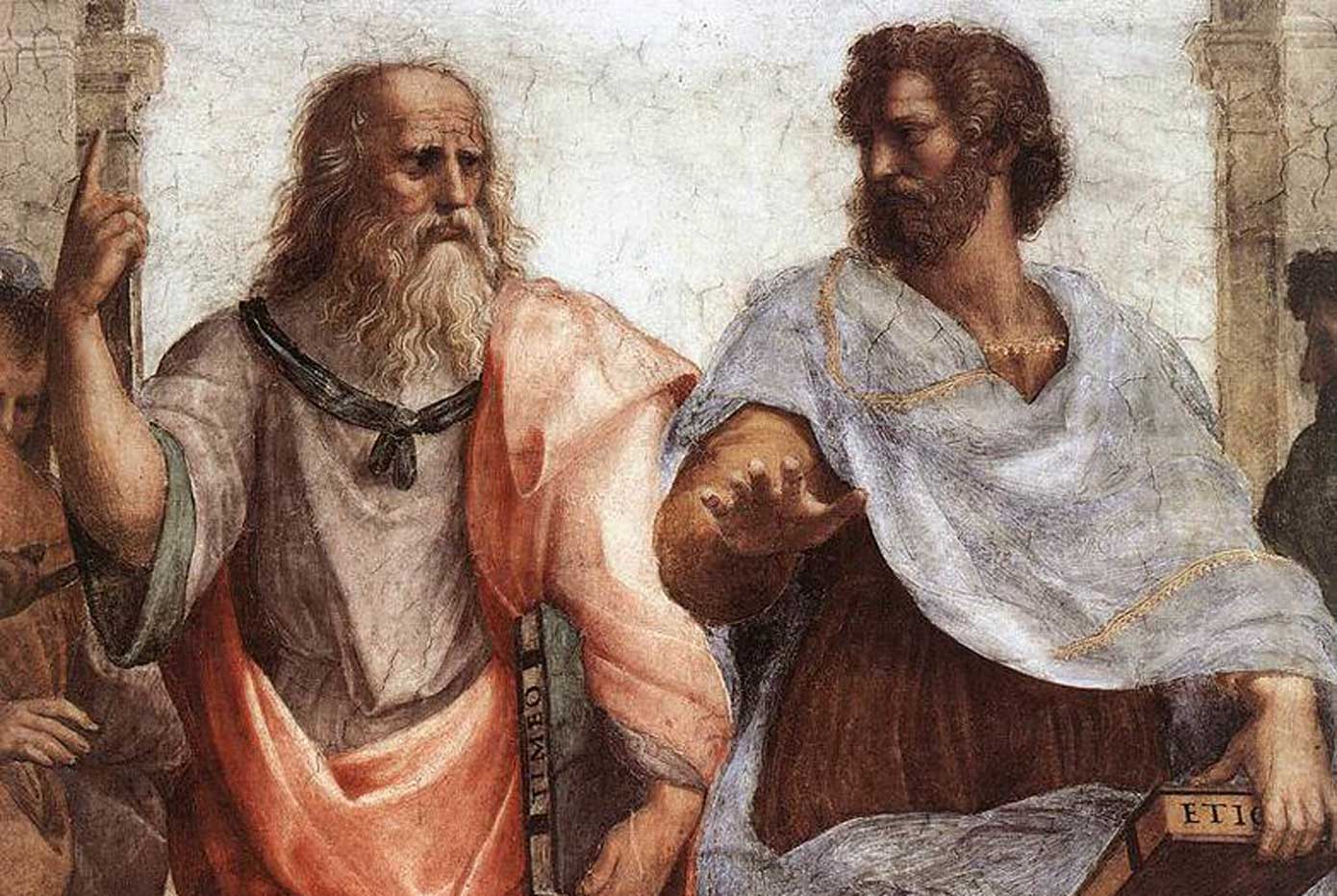

For many of the classical philosophers, the emotions were difficult to properly assess, particularly without today’s benefit of advanced scientific and psychological knowledge. The best answer they had was that emotions were purely sensory experiences, except less useful to us than our other experiences. Specifically, the definition was boiled down to this: “emotions are feelings understood as primitives, without component parts”.

So yeah, for Plato, feeling sad was like tasting chocolate. There is no particular control over the response you experience, and it is a response unique to you, but that is all it is. And yes, sometimes these responses are misplaced, and can be foolish, and of no informational value. Stop crying, it’s pointless.

Seems reductive, doesn’t it? I mean – by this definition, are emotions even real? Don’t worry, the big thinkers really suss it out by the end of this.

The James-Lange theory said that ‘emotions are physical reactions to external occurrences’…

Then came the slightly-more-sophisticated James-Lange theory, named for two guys who kind of said the same thing. Mr James and Mr Lange were both of the view that “emotions were feelings constituted by perceptions of changes in physiological conditions relating to the autonomic and motor functions”.

This is quite a tidy little definition – and seems about right. We can agree that when we feel embarrassed, our face goes red; when we are sad, tears fall; when we are frightened, our breath gets shallow; and when we are nervous, our stomach does a backflip, or a front-flip, or goes all fluttery.

The James-Lange Theory describes that these physical changes signal the occurrence of these emotions, which makes them real. The problem is, what about the emotions that don’t necessarily earn a physiological response? Slight sadness, or contentedness, or indifference? Neither James, nor Lange, had the answer.

In the 1960s, psychology-influenced thinkers suggested that ‘emotions are cognitive events’…

So then in the swingin’ ‘60s, there was a bit of a mini-Enlightenment when it came to psychology, and some theories came about as to how to evaluate emotions, in both philosophical and psychological schools of thought. The psychologists and philosophers came together, all dressed in mod mini-dresses and white pleather boots, and just said, “what are emotions, anyway?” Is a feeling a reaction – or is it a cognitive event in itself? Can an emotion arrive in your body in the same way an idea does? Picture that lightbulb that appears above cartoon characters’ heads when they think of something new. Ding!

Philosophers considered a constitutive theory of emotions – suggesting that emotions are cognitions in themselves. This idea describes an emotion to be a recognition or evaluation of something, occurring within the us – the person experiencing the emotion. Philosophers quite like this description of an emotion – it is nice and tidy and logical. In psychology, it’s said that emotions are not cognitions in themselves, but caused by the occurrence of cognitions. This theory is more popular among psychologists. Philosophers don’t like it because it doesn’t fully explain what an emotion is – but rather what it’s caused by.

In the 1970s, Silvan Tomkins said that ‘emotions are fuel for our actions’…

All of this confusion has been relatively cleared up by the endearingly-named philosophical pioneer Silvan Tomkins. He was the first one responsible for drafting basic emotion theory, back in the 1970s. In his theory, Tomkins talked about “the primary motivational system” within human beings. Picture an engine that uses certain fuels to power the human being’s various actions. These fuels are the emotions – nine, in particular, according to Tomkins (enjoyment, interest, fear, shame, surprise, anger, distress, contempt and disgust). Some fuels are more powerful than others. The power of each fuel is based on whether it causes pleasure or pain. Anyone who has shut a door both in fear and in anger, know that those fuels have very different efficacies…

So the emotions are fuel for our actions. However, the emotions can also be – airbags. Let me explain.

In the 1990s, Paul Ekman said that ‘emotions protect us from life-changing/life-threatening events’…

The Tomkins theory was advanced in the 1990s, after Paul Ekman suggested that certain emotions had actually evolved within humans, to better equip them for dealing with certain difficult events that are relatively unavoidable for humans, such as “fighting, falling in love, escaping predators, confronting sexual infidelity, experiencing a failure-driven loss in status, [or] responding to the death of a family member.” Big events – usually ones involving significant change – don’t just result in big emotions. They actually require big emotions, in order for us to deal with them, and adapt, and hopefully, survive.

Whether or not you agree that crying at sad movies or shrieking at the sight of a mouse are reactions that characterise us as highly evolved, superior beings, it’s clear that emotions are far more than what the classic thinkers labelled them. They are of value, they are full of information. They are fuel, they are airbag, so – let the tears flow.

Check back in next week for the second instalment of Thinker’s Corner on Pleasure and Pain.

LOVETHEGLOSS.IE?

Sign up to our MAILING LIST now for a roundup of the latest fashion, beauty, interiors and entertaining news from THE GLOSS MAGAZINE’s daily dispatches.