Vogue, Virago and The Legendary Carmen Callil …

In April 1974, a young and beautiful woman, sitting in a London underground train on her way home from work, read a book review in Vogue – and my life was changed. Vogue wasn’t this extraordinary woman’s tipple and she certainly didn’t associate it with literary material so she was knocked back when she read, “If I had to choose one shelf from my library to take to a desert island I would seize that row of beautifully produced, distinctive dark green paperbacks with their felicitous covers of fine but usually not well-known paintings chosen to counterpoint or complement the contents and chosen with the same skill and care that goes into all of Virago.”

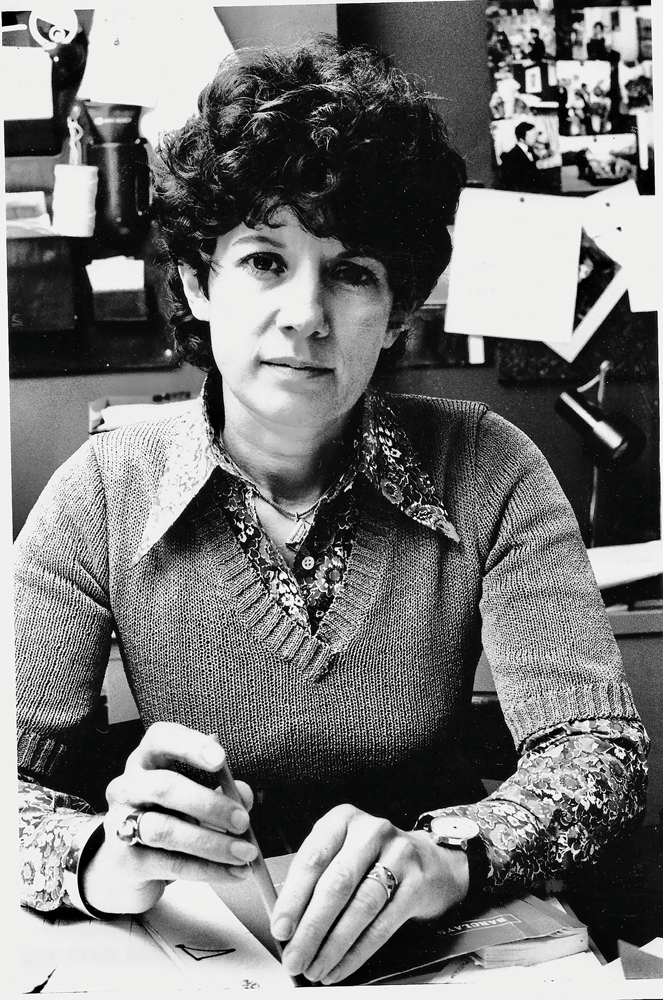

That woman was Carmen Callil and she had more or less invented the feminist publishing press called, appropriately enough, Virago, and I had written the review and I know all this because she telephoned me the next day to say how delighted she was. I didn’t know Carmen then, but I knew a lot about her, admired her as a feminist radical publisher and was somewhat intimidated by her reputation as formidable and fearless. She seemed the opposite to an exploited, witless, unwoke writer working on a magazine that was concentrated on feminine stuff.

We arranged to meet and over the years she became my dearest and closest friend. Fifty years. (Only Nuala O’Faolain ever had an equal place in my heart, and I lost her too.) But one can only claim so much in friendship and I can only hope she felt like that about me. Carmen was so much to me – my ballast, my moral compass, my fiercest critic and admirer, my publisher, my brilliant editor. We talked every day, met twice a week for supper and a silly game of Bananas, texted, referred everything to each other, loved the same writers, movies, did hatred well, tore each other apart never to speak again and next day went walking with our beloved scruffy dogs. (We had a lighthearted arrangement that whoever of us died first, the other would adopt the other’s dog.)

We went on holiday together, either just the two of us or with my family (she had no children and never married though many men asked her). Wherever I went – forever in-flight mode – in France, Ireland, Camber, Somerset, Paris, she came and stayed. (Never in New York because she indiscriminately abhorred anything to do with North America.)

I always drove to wherever and we would bellow Catholic hymns all the way, down autoroutes, through Provencal villages, through the Kent countryside, and along the Flaggy shore and up past Ben Bulben, with the sound of Faith of our Fathers or Tantum Ergo or Sweet Heart of Jesus ballooning out behind us, two happy lunatics in a car, trying to exorcise our horrible convent schooldays. (Her mantra: “If you’re convent-educated, you have no self-confidence at all.”) She never took the least notice of my fast driving, wrong diversions, or near misses, quite unmoved, except once when the primitive SatNav told us to turn sharp right in the middle of the Gault Millau bridge (343 metres high) and she said mildly, “I shouldn’t, if I were you.”

More often than not in the latter years she was working on her own two great moral books – Bad Faith: A Forgotten History of Family and Fatherland, a biography of the appalling Louis Darquier de Pellepoix and of Vichy France, published in 2006. One reviewer described it as “a book of devastating power, written with a novelist’s eye for character and with an acute delineation of secrets, loss, and grief”. Oh Happy Day, about her mother’s side of the family and the appalling poverty of her ancestors in 19th-century England, “unearthed her family’s past in a book that is both a heartfelt outpouring of pity and sorrow and an irate demand for restitution”. Both books were born from outrage, from her personal and familial tragedies, her steadfast ethicality and integrity, and her determination to change the world. That last point was her salient point – the core of her existence – she wanted to live to change the world, not just through books (which she did) but in every sphere, and she never stopped striving towards this, putting the rest of us to shame. That ceaseless campaigning energy was astonishing to watch and impossible to keep up with. I often felt ashamed about my own passivity in the face of what I saw as inevitable – Carmen thought nothing was inevitable.

She was both Australian and Irish and proud of both. Most of her forbears came to Australia for religious reasons. Her Irish great-grandparents James Keane and Johanna O’Leary were from Cork and Tipperary, her Lebanese family from Bsharri (The City of Churches) in North Lebanon. The family matriarchs travelled to Australia carrying the precious laban (yoghurt) which is still to be found bubbling and squeaking in every Lebanese family’s airing cupboard (including, until now, Carmen’s in Notting Hill.) She knew that her forbears had had a harrowing time making their way in their new land, had started out by becoming journeymen pedlars. But they were all merchants, quickly became rich and opened the biggest shops in Melbourne. She was so funny about, so proud of, so amused by, her family: “Callils were thick upon the ground in Melbourne,” she said, “disturbing the peace generally. I was a Melbourne Catholic with an excessive number of eccentric religious relations. (She once wrote that Ian Paisley could have popped over to the Lebanon at any time and merged into a happy throng of raving bigots.)

Her stories! Oh, her stories! Her grandmother, a stern mountain matriarch, came from one of the most warlike of the seven clans of Bsharri and her force of personality erupted from the kitchen where Carmen would see her pounding kibbe and creating eternal family feasts. Carmen’s mother – Lorraine Allen – was a voracious reader and inspiration to Carmen; her father was a barrister and lecturer in French at Melbourne University. They lived across the road from the large headquarters of the founding family. “They furnished my theatre of life with generosity, eccentricity and vigour, and I hated, feared, and loved them in equal measure. They were tremendously argumentative. Even those words don’t seem sufficiently strong for the decibel level of their narrative and conversation. They truly liked a nice row. This overabundant parade of Callils provided me with the standards by which I would lead my life, for good or ill.”

What Carmen did for all of us women is beyond words – her generosity, the care she took with finding and resurrecting lost work, the ravishing intelligence lavished on celebrating women writers and their lives…

After the death of her beloved father, Carmen, aged nine, was sent to stay with her aunt Mary. “I first realised she was mad when we knelt down after supper, – some extremely dubious form of Lebanese food – to say the rosary for my father. For Aunt Mary, the rosary was whatever she wanted to dish out: not for her ten Hail Marys five times over. Being a good convent girl, this was agonising to me, so I would try to intersperse a quick Hail Mary or two, under my breath, to bring the numbers up to the required level. This led inevitably to silence on my part as I was careering through additional Hail Marys at times when she expected me to reply to some incantation she had stuck in on an ad hoc basis. ‘Can’t you even pray for your poor dead father!’ she would scream.

“I’d see her on the tram home from the University and I’d try to hide to avoid the embarrassment of exchanges with her tempestuous person. She was top of the Callil shouting league and of course would spot me hiding and would shriek through the packed tram: ‘There she is, my dead brother’s child and she won’t say hello to her aunty!”

All her family were gamblers, (though Carmen wasn’t) and her father’s addiction to horses, cards, backgammon, and his passion for books, meant he would often stay in bed till the afternoon, and if he had a tutorial in the morning, would turn up in his pyjamas. When he died, he left her mother racehorses, an overflowing library and a good part of the greyhound coursing club in Melbourne and deep grief all round.

Carmen left Australia immediately after university in Melbourne and headed to Italy for two happy years and thence to London where she put a succinct advert in The Times: Australian, BA, wants job in book publishing. She got it and had found her metier.

The idea of a feminist publishing company came to Carmen, “like the switching on of a lightbulb” when she was working on the establishment (if that is ever the word in our lore) of the feminist magazine Spare Rib, founded in 1972 by Marsha Rowe and Rosie Boycott, now a Dame and a Baroness. (Carmen also became a Dame, to her slight embarrassment as a fervent republican. But she understood it was recognition.) She founded Virago Press in 1973 and the title Virago was a beacon – blazing out the principles of this new company to rescue and radically expand the vast number of books by women, forgotten and ignored, over the centuries. Its other great aim was to transform the role of women in publishing – and it did. She became the most brilliant publisher of her generation. A quote from the great socialist feminist Sheila Rowbotham featured on every copy: “It is only when women start to organise in large numbers that we become a political force and begin to move towards the possibility of a truly democratic society.”

In 1978, Carmen started the series, Virago Modern Classics: “If founding Virago was my first lightbulb moment, dreaming up Classics was my second.” It was a huge success. When it came to choosing them, her own memories and her mother’s voracious reading were the earliest inspiration. “I got Willa Cather from my mother – she read everything, and she was the only woman I knew who had read Pilgrimage by Dorothy Richardson from cover to cover.” (It does span 13 volumes!). The book Carmen chose for her Desert Island Discs episode was written by a woman under the pen name of Henry Handel Richardson, which tells its own story.

I was proud beyond words when my first book was republished as a Virago Classic. (When that book was first published there were 27 literary editors in London, 26 of them men, all apparently in love with Martin Amis, Ian McEwan, Saul bloody Bellow, Jeffrey Eugenides etc. We didn’t have much of a chance.) What Carmen did for all of us women is beyond words – her generosity, the care she took with finding and resurrecting lost work, the ravishing intelligence lavished on celebrating women writers and their lives and opportunities or lack thereof, giving us through Virago and Virago Classics the heritage we didn’t even know we had, the fruits of women’s work and imaginings which had been stifled for so long by the bloke culture in which we lived.

She opened doors into our lost literature, English and Irish, giving credit where credit had never been given. She rescued so many wonderful books from oblivion. (She loved Molly Keane’s, Kate O’Brien’s and Mary Lavin’s books.) We tallied on our favourite authors and were inordinately pleased when early on we discovered that we both adored Georgette Heyer. She was always on the go – her cracking campaigning spirit never flagged. She was vitriolic about government misdeeds and privileges and civil inequalities, wrote articles and essays to highlight wrongs, published pamphlets, went on protest marches, demonstrated against climate change, railed against Britain’s imperial past, campaigned furiously against Brexit and started a Remain movement (48 & Rising) after the shocking result.

She was powerful. Managing Director of Chatto & Windus and the Hogarth Press, a member of the board of Channel 4 Television, a member of the committee for the Booker Prize. She won so many awards and prizes – the Damehood of course and the Benson Medal from the Royal Society of Literature – but never mentioned them. And have I mentioned that she was very beautiful?

Carmen was never a pundit although she was often on television, making her point fairly forcefully. You could see interviewers coiling backwards – but every opinion, every sentence, was newly minted from fresh evidence and anger. As a fanatical cricket fan – a supporter of the England team, she once caused a sensation on Newsnight about the Australian cricket team, calling them “poofters” for having dyed hair. Presenter Kirsty Wark said: “Maybe they are entitled to their feminine side when they dye their hair?” Carmen said firmly: “No, it’s not a feminine side, it’s sort of a poofter side, isn’t it?” Kirsty, visibly shocked said : “Oh my God, Carmen. You may say that – I would never say that.”

Finally last year – she was 83 and thought she’d better get on with them – she started in on her memoirs with much grumbling and moaning, but she took time off to come to my daughter Daisy’s birthday party in September and on the way home she planned our future – that somehow, soon I would publish my short stories, she, her memoirs. She said she was worried because her legs were swelling oddly. But then again, she was always complaining about her legs, thunderthigh Mount Lebanon legs she called them, evolved, she said, by her clan having to run up the mountain from their enemies, and envied my perfectly ordinary ones. But when I saw her legs, I knew it was something bad, to do with the lymphatic system, and I was alarmed, terrified in fact. (I’d never got over my fright about Nuala’s sudden diagnosis.) And I was right. A few days later, she was told she had four weeks to live unless a drastic course of chemo would work. It did not. She had only one lung and she couldn’t do it. She suffered.

There is no way to express the insane shock, anger, disbelief, dread and panic felt by her friends. She had an extraordinary capacity for friendship and was much loved, adored actually. Every one of her many friends – and there were hundreds – were made to feel the most loved, the most important, the only genius. I suppose, like everyone, I believed I was first in her affections. One of the biggest churches in London was packed to the rafters at her funeral and as the choir belted out Abba’s Fernando –Yes, if I had to do the same again I would, my friend – it was to the accompaniment of Literary London crying.

Right to the end of her life she was in the thick of life. The end of her life. I can’t believe I am writing those words. I don’t believe them. But she’s not here and her dog Effie sits at my feet, and I am in tears.