Finnish author Tove Jansson (1914-2001) best known as the creator of the world-famous Moomin stories and author of The Summer Book, for 40 years shared her life with the graphic artist Tuulikki Pietilä. In the bitter winds of autumn 1963, Jansson raced to build a cabin on an island in the Gulf of Finland which would become their summer refuge …

For 26 summers, writer Tove Jansson and her life partner, the graphic artist Tuuliki Pietila (known as “Tooti”) would migrate to the rocky, almost barren island of Klovharun, at the edge of the Pellinge archipelago in the Gulf of Finland. They had made this “fierce little skerry” their home in 1963, building a cabin with the help of a maverick builder-fisherman called Brunström. For Tove and Tooti it offered the chance of solitude. Tove had previously shared the nearby island of Bredskär (the setting and inspiration for Tove’s novel The Summer Book) with her mother Ham and her brother Lars and his young daughter Sophia.

Bredskär was leafy and welcoming, with sheltered inlets. Klovarhun, by contrast, was stark: the preserve of warring gulls and terns. Life here was precarious and austere. Yet both Tove and Tooti were energised by it. They relished the storms that would lash the granite rocks, marooning them for days, the need to fish to supplement provisions and to collect driftwood for fires. As if to draw even closer to nature, they chose to sleep in a tent pegged to a platform on the rocks, leaving the small cabin they had built as a space to work in or to house their guests – Tove’s mother Ham was a frequent visitor and occasional boat-parties of friends would arrive from Helsinki.

But as Tove and Tooti reached their mid-70s, their confidence in coping in such a harsh environment began to ebb. Even worse, the exhilaration they had felt at storms and rough seas had given way to unease. A system of signals was arranged – a raised f lag or a call on the walkie-talkie – to reassure those on Bredskär that all was well. But they knew their last summer was approaching. They had told each other they would relinquish the island before age and anxiety forced the issue and in 1991 they kept their word. In 1991, they signed a gift deed so the cabin could be used by hunters and fisherfolk, pinned up notices explaining its quirks, and left. They would never return. Indeed, such was the grief of separation that it would take nearly four years for Tove to allow herself to discuss Klovharun, and to begin the unique collaboration that would lead to Notes from an Island, a moving homage to an enduring relationship and to a tiny, rugged island. Published this month in English for the first time, Notes from an Island recounts the tale. Read an extract from the book below.

Tove Jansson on Klovharun, 1969. Photograph by Olov Jansson.

I love rock – sheer cliffs that drop straight into the ocean, unscalable mountain peaks, pebbles in my pocket. I love prising stones out of the ground, heaving them aside and letting the biggest ones roll down the granite slope into the water! As they rumble away, they leave behind an acrid whiff of sulphur.

I search for building stones or just for pretty rocks to make mosaics, bulwarks, terraces, supports, smoke ovens, strange unusable structures made just for the sake of constructing, and for making piers which the sea will carry away next autumn and which I’ll rebuild better for the sea to carry away all over again.

I am a sculptor’s daughter, but Tooti’s papa was a carpenter, so she loves wood, whether she’s working with beautiful, heavy lumber or playing with featherweight balsa. We searched for juniper in the woods. Along the shore we managed to find unfamiliar hardwoods with unknown names. From these, Tooti carved the kinds of tiny objects that take time and infinite patience – for example, the smallest salt spoon ever made.

But, says Tooti, when you’re building big, that’s completely different. You need determination and total confidence in your ability to estimate and measure and get things right, down to the centimetre. No, to the millimetre.

Sometimes we build things to be solid and lasting and sometimes to be beautiful, sometimes both. Incidentally, Tooti does her wood engravings in beech or pear and her woodcuts mostly in birch.

She often discussed materials with Albert Gustafsson in his boat shed in Pellinge; they also talked about boats. He gave her some small pieces of teak and mahogany to play with, and Tooti took them home and came up with some totally new ideas. It was Albert who built our boat, in 1962, of mahogany, four metres long, clinker-built. It was the prettiest boat anyone had ever seen along that whole part of the coast. She was strong and agile and positively danced on the waves. Her name was Victoria, because both Tooti’s father and mine were named Viktor.

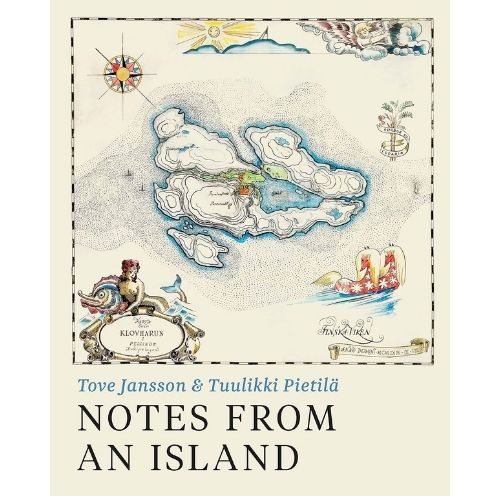

“Klovharun is about six to seven thousand square metres, shaped like an atoll with, in the middle, a lagoon surrounded by granite outcroppings except for two shallow gaps, one on either side, which connect it with the sea.”

Later, as the summers passed, Victoria became more and more Tooti’s boat because she loved it the most and lavished care and attention on it.

There are many words for island – isle, skerry, holm, reef, atoll, key. The coastal charts for Pellinge archipelago show a crescent of uninhabited skerries west of Glosholm, perhaps the result of a capriciously formed ridge down on the sea floor. Kummelskär is the largest and prettiest pearl in this necklace.

I was still very young when I decided I’d be the lighthouse keeper on Kummelskär. Granted, the only thing out there was a blinker beacon, but I was going to build something much bigger, a lighthouse so tall that I could see and watch over the whole eastern Gulf of Finland – that is, when I grew up and was rich.

Gradually my dream of the unattainable changed and became a game with the feasible and eventually merely a stubborn, irritated refusal to give up, until finally the Fishing Association told me in so many words that I was going to distress the salmon, so that was the end of that. But about two-and-a-half nautical miles from Kummelskär, in toward the coast, there were some small islands that no one really cared about. One of them was Bredskär, and it was available for leasing.

It’s remarkable that such a huge, enduring disappointment can so quickly be forgotten, exchanged for a new infatuation, but so it was. All of us who moved to Bredskär came quickly to the conclusion that we had found paradise. We improved and repaired in high spirits. We had everything, albeit in miniature – a little forest with a woodland path, a little beach with a safe place for the boat, even a little marsh with some tufts of cotton grass.

We were proud of our island! And we wanted to get approval, to show it off. We asked people out and they came, and came back, summer after summer, more and more, sometimes they brought a friend and sometimes the loss of a friend and they talked and talked about their yearning for the simple, the primitive, and, most of all, their longing for solitude. Gradually, the island filled with people. Tooti and I began to think about moving farther out. We made a half-hearted try for Kummelskär, but this time they said we’d distress the cod.

On beyond Kummelskär there’s Musblötan, Käringskrevan, and Bisaball, somewhat inaccessible skerries where only fishermen and hunters ever go ashore, and the last one in the row was Klovharun, in other words, a skerry – a haru – cloven in two. That’s where we wanted to build.

Klovharun is about six to seven thousand square metres, shaped like an atoll with, in the middle, a lagoon surrounded by granite outcroppings except for two shallow gaps, one on either side, which connect it with the sea. At low water, the lagoon becomes a pond.

It is said that at one time seals used to play in the lagoon, until they learned better and moved farther out. The coastal charts indicate that these scattered islets are owned by the state, but that’s simply not the case.

In fact, according to some original documents from the time of the great land reform in the 1700s, there was disagreement at an administrative meeting – perhaps further confused by the absence of the recording secretary due to poor travel conditions – as a result of which these small islands were hastily assigned to Pellinge township, the definition of which was not precisely stated.

Over the years, the village population had increased significantly and it didn’t seem possible to ask everyone for permission to lease Klovharun. But like so many other free-spirited islands, Pellinge had its own prophet whom one could consult about delicate questions regarding the archipelago’s internal affairs. He advised us not to get our hopes too high and above all not to rely on legal documents, which sooner or later only cause trouble. In other words, no lease, but maybe a small donation to the Fishermen’s Association. “Make it easy for yourselves,” he said. “Post a list in Söderby with Yes and No. If I sign my name under Yes, everyone will probably go along.”

We put up the list with Yes and No on the veranda door at the general store and we got Yeses all the way down. We sent the list to the Borgå district government and applied for a building permit.

While we waited, we lived on Haru in a tent. It rained the whole time. Tooti read The Vicomte de Bragelonne, volume six. “There’s nothing like the classics,” she said. “Read Les Miserables, unabridged, and then you’ll understand. You have to be loyal.” I know that Tooti is loyal to what she believes, even afterwards. We’d pitched our tent right next to the Big Boulder, which is so massive that it had become a landmark, at least for people who navigate by hearsay. The boulder is estimated to weigh about 50 tons. It lies in a huge frog pond at the only spot suitable for a building a cabin that’s out of the ocean’s reach.

It rained all week. The pond overflowed and trickled down the rock face right past our tent and smelled awful. We dreamed about what our new cabin would look like. The room would have four windows, one in each wall. Toward the southeast we’d need to see the big storms that rage right across the island, on the east, we’d see the moon’s reflection in the lagoon, and on the west side there’s a rock face with moss and polypody ferns. To the north, we’ll want to keep watch for approaching boats so we’ll have time to get ready.

We figured that if we were going to build a cabin, it ought to be fairly high up on the slope, but not at the top, because that’s only for the navigation marker. Maybe just a little way down, so that from the gulf, and from the boats that rush past for no good reason, only the chimney is visible, in silhouette against the light.

Late one evening we heard a motor shut down at our beach, and someone with a flashlight came slowly up the slope. He introduced himself. Brunström from Kråkö. Brunström was out salmon fishing and was going to spend the night on his boat. Then he saw a light on the island. We made tea on our Primus stove.

Brunström is rather small. He has an austere, weatherbeaten face and blue eyes. His gestures are quick but measured, and he uses no adjectives in everyday speech. His boat has no name. We trusted him immediately.

Brunström had heard about the Yes-and-No list. “It’ll never work,” he said. “Not even in Borgå where they’re pretty loose, you know, easygoing, you’ll never get a building permit. All you can do is just start building, right away. It takes a really long time for bureaucracies to figure out what they want to do, so you have to seize the moment. The law says that no building can be torn down if the builder has framed as high as the roof beam. Believe me,” Brunström said, “I know what I’m talking about. I’ve built cabins in no time, one here, one there, if only to annoy certain people in Pernå, for example, or Pellinge.”

Brunström told us he wouldn’t need much time, although you never knew with autumn weather. He’d bring Sjöblom and maybe Charlie and Helmer, and for starters, they’d have to blow up the Big Boulder.

Brunström said that dynamiting and excavating for a cellar doesn’t count as construction. Construction means framing, and framing won’t last the winter without a roof. So we have to hurry. “Before it snows,” he said.

Extracted from: Notes from an Island, by Tove Jansson and Tuulikki Pietilä, published by Sort Of Books, £12.99stg.

She is the queen of no makeup makeup and even manages to make a smokey eye look subtle. When everyone else was going for heavy contour and laminated eyebrows, she continued to promote enhancing your natural features with simple tricks and smart product placement. If you have seen any of her videos, you will notice how little product she actually uses. Even Victoria Beckham commented how surprised she was when she went to remove her makeup after a shoot with Lisa on how little product was applied.

LOVETHEGLOSS.IE?

Sign up to our MAILING LIST now for a roundup of the latest fashion, beauty, interiors and entertaining news from THE GLOSS MAGAZINE’s daily dispatches.