Underestimate the social, economic and political impact of fashion at your peril! SOFI THANHAUSER explores how Marie-Antoinette’s wardrobe helped spark a revolution. Ironically, it was not the fine silks and embroideries that triggered the mob, but her affectation for a simpler life and wardrobe which caused the devastation of the Parisian fashion industry …

Susan Sontag noted once how “the French have never shared the Anglo-American conviction that makes the fashionable the opposite of the serious.” Never was this more true than in the 18th century, when serious people spoke about fashion, just as fashion remarked on serious subjects. The most famous, and famously irreconcilable, philosophers of the Age of Enlightenment, Voltaire and Rousseau, duelled on the subject of fashion, and in particular over whether fashion-fueled consumption was of any benefit to the public. Rousseau became extremely influential on the reform of French dress, especially for children. French children were dressed exactly like adults until Rousseau suggested that children be given more room to move. Parents starting dressing their children in comfortable sailor suits. Rousseau himself had produced a spectacle by eschewing the wig, breeches, and waistcoat of court fashion for the long, loose robe and round cap of his Ottoman “Armenian” suit that made him the laughing stock of the salons. After his death, Rousseau’s arguments for rustic simplicity would, through the unlikely figure of Marie Antoinette, remake the aristocratic wardrobe.

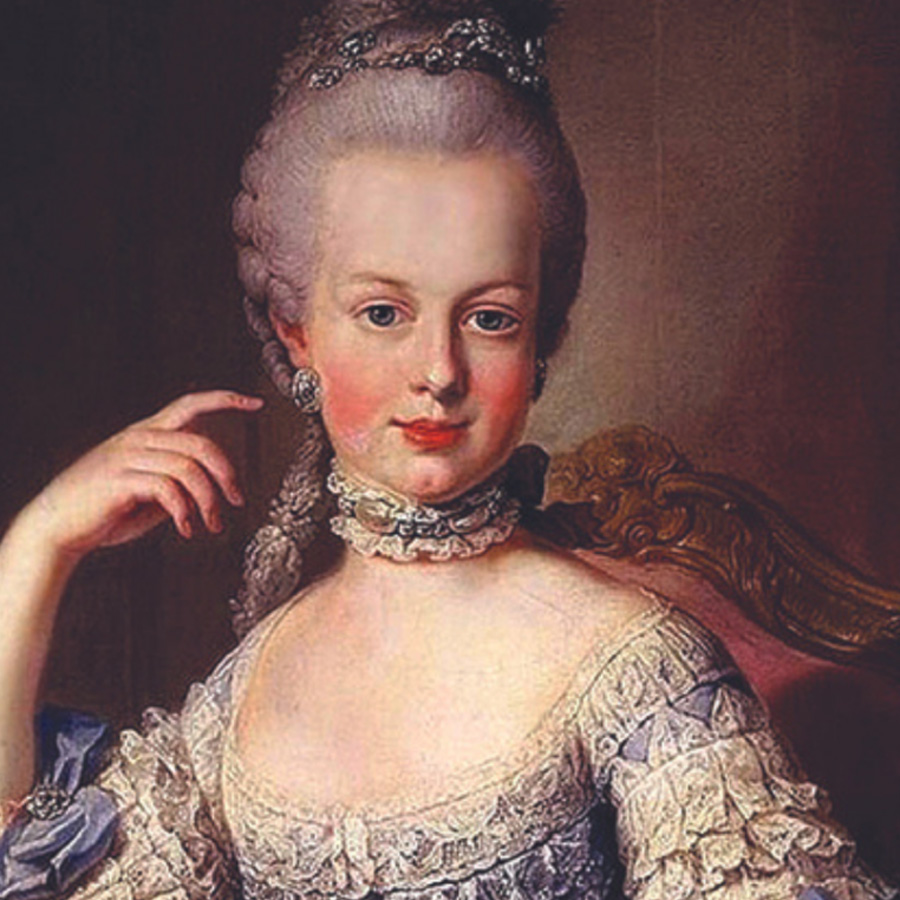

In the last quarter of the 18th century, Marie Antoinette was France’s major fashion icon. Traditionally, this position had been held by the king and his mistresses, but Louis XVI had neither an interest in fashion, nor a mistress. At Marie Antoinette’s side was the celebrated Marchande de Modes [fashion merchant], Mademoiselle Bertin.

Marie Antoinette and Mme Bertin were blamed, together, for the intensification of fashion worship, even for families’ financial ruin caused by overspending wives of noblemen. Upon the queen was also pinned, of course, responsibility for famine and the French national debt itself. Historians have noted that her expenditure on clothes, while large, essentially represented her keeping up with what was expected of her. Symbolically, however, she was luxury personified.

None of Marie Antoinette’s famous excesses, however, evoked more fury than her turn to simplicity. Never one to miss out on a fad, Marie Antoinette read Rousseau during his great vogue, and personally made the popular pilgrimage to his tomb. She then remade herself after his vision of “simplicity.”

Marie Antoinette’s pastoral period corresponded with the construction of the Hameau de la Reine, the queen’s rustic retreat in Versailles, in 1783, as well as her 30th birthday, after which youthful styles no longer seemed appropriate. The dress of the French peasantry became a fetish in French high society. Having run through an orientalist streak, with dresses à la Chinoise and à la Turque, the exoticism of the French provinces was evoked, no doubt, as a last source of zest for the jaded palate. The nobility started wearing elements of peasant dress like aprons, straw hats, bonnets and lappets. In the September 1788 Magasin des Modes Nouvelles the caption beneath a fashion plate of a “woman dressed as a court peasant” read, “This get-up is almost the only one that our ladies find acceptable for morning walks.”

Had these gestures only been tasteless, perhaps they would not have been so detested. But in fact, the queen’s turn in the 1780s to muslin “chemise gowns,” and the general vogue for imported muslins and gauzes, had disastrous implications for Lyon silk. “The superb manufacture of fabrics of silk, gold and silver which French commerce prided itself on, which furnished all of Europe, and provided subsistence for thousands of men, has been ruined by the fashion for cottons, muslins, gauzes, and linen,” wrote the journalist Proudhomme. Silk gowns were no longer wanted in private life, and kept only for holidays and formal occasions. In 1786, there were 12,000 silk looms in Lyon. By 1789 that number dropped to just 7,500. Honoré de Balzac once described the French Revolution as “a debate between silk and broadcloth”, but the popularity of the muslin chemise gown, almost a decade before the Revolution, had already dealt a blow to Lyon and to silk.

The Revolution demanded another costume change. After storming the Palais de Tuileries a mob ripped Marie Antoinette’s wardrobe to shreds. “All the rich suits of clothes were pulled to tatters, and every one sought to decorate his or her person with some fragment of the devastation,” one spectator recalled. “How many curious women visited her wardrobe! How many bonnets, elegant hats, pink petticoats, flew from the room!” In the spring of 1793, the Revolutionary government put on a sale of items appropriated from the palace, including the remaining wardrobe of the king and queen. One spectator remarked: “I saw a suit embroidered with peacock tails that had cost 15,000 livres sold for 110 livres.” Decadent clothes and fabrics such as these were anathema. Simple wool sold for more.

The Revolutionaries insisted not only on destruction of the old costume, but the positing of a new one. Trousers became the totem of the lower-class sansculottes, a term which literally translates to “those without breeches”. An article in the 1792 Encyclopédie Méthodique about shirt collars argued that “we ought to make this part of our manners, our customs and our costumes, the same changes we are now making to our Constitution and our laws.”

The Reign of Terror that followed the removal of French royalty also destroyed existing professional and patronage systems, and devastated Parisian workers in the luxury trades. One woman recorded: “My mother makes accessories and anything to do with fashion; my sister can make lace and gowns, I can sew and embroider. The embroiderers are going bankrupt, the fashion merchants are closing their shops, the dressmakers have sacked three-quarters of their workers. We are dying of hunger.”

In Paris, the fashion for simplicity in dress turned out to be just that, a fashion, and conspicuous consumption came into vogue again by 1799. Still, the French luxury trades had been altered. Years after the Revolution, the duchess d’Abrantès wrote with notable bitterness that the so-called “equality” of the post Revolutionary period came in the form of a universal cheapening: “It has been alleged that everything has been simplified, that every article has been placed more within the reach of persons of all classes. That is true in one sense; that is to say, our grocer shall have muslin curtains and gilt rods to his windows, and his wife shall have a silk cloak like ours, because that silk is become so slight and so cheap that everybody can afford it. You will have bad taffeta, bad satin, bad velvet, and that is all.”

In the span of a few short years, guilds, artisans, and the traditional patronage system of Parisian fashion were lost. Their mythos, however, was to prove more durable. Many contemporary goods are designed for obsolescence, but with clothing, rapid turnover can draw upon a much deeper well of fantasy than can, say, a refrigerator. An article of clothing can evoke a period before the birth of industrial capitalism, when cloth was handmade and clothes made to measure, and a time when dressing in the silk formerly reserved for the elite became accessible to all members of society. Clothing manufacturers learn early on that in a trade based on fantasy as much as it is on necessity, they aren’t simply in the business of selling fabric, cut and sewn. Rather, they are selling glamour, and the glamour of Parisian fashion had no equal.

Worn, A Peoples’ History of Clothing, by Sofi Thanhauser (Allen Lane, €25) is out now.