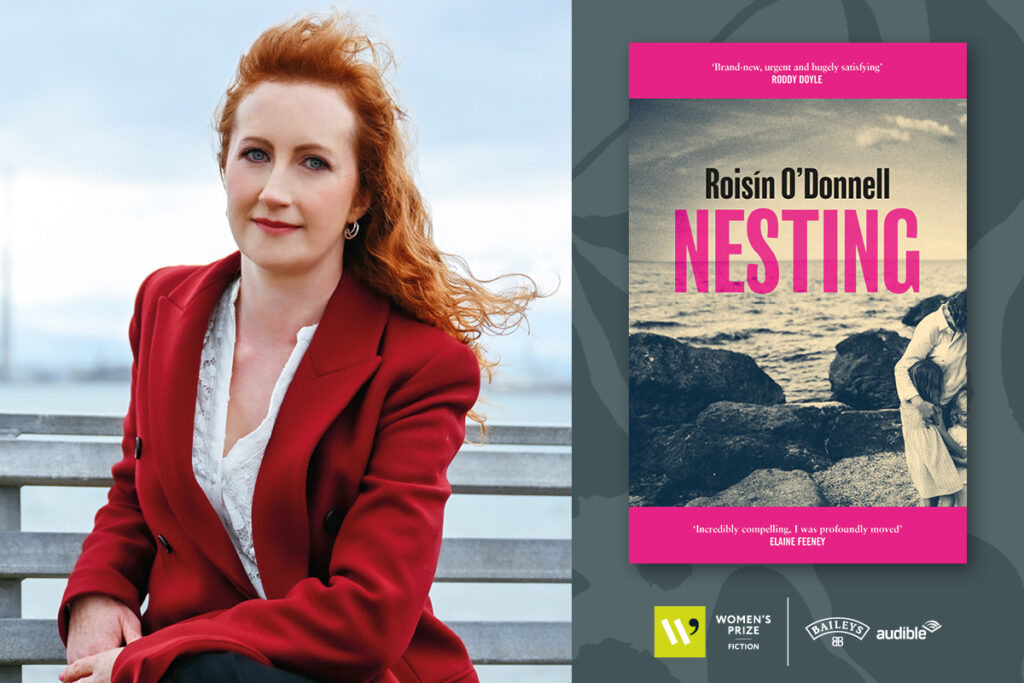

In her debut novel, Nesting – longlisted for the Women’s Prize for Fiction 2025 – Roisin O’Donnell conveys the confusion of living in a coercively controlling relationship …

You came from a happy home and are educated and professionally competent, so believe you could never be the victim of domestic abuse. However, at a cellular level, you know something is off in your relationship, but you don’t have the words to describe it.

The fictional main character Ciara sometimes questions herself as to whether or not she is the victim of domestic abuse. Outwardly, her life is good. Married to Ryan, an expensively suited civil servant in the Department of Public Expenditure, they have two little girls and a third baby on the way. Because Ryan is not physically violent to her, Ciara not only doubts herself but finds it hard to convey the seriousness of her situation to the authorities.

“I cannot hear myself think. I do not know who I am anymore. I do not if I exist. I feel like a ghost. Life energy drained. A bloodless, cowered feeling.”

Coercive control became a criminal offence in Ireland in 2019 and is an umbrella term for a series of tactics abusers use to control their partners. Whether behaviour in a relationship reaches the threshold for coercive control is a complex question, but what red flags should we look out for?

It varies, but often, financial abuse will be present. Controlling all of the household income and keeping financial information a secret. Having control over spending, checking receipts, and having everything in his name.

Micromanaging and monitoring how a woman spends her time, tracking what she does online or on her phone, restricting her movements in subtle ways or preventing her from seeing friends and family, isolating her, in other words. Or even always being there when she meets others.

A common component of coercive control is psychological and emotional abuse, which can be challenging to identify or describe. That’s why it’s so insidious and has a profound impact. One highly effective technique that abusers often use is gaslighting, which is designed to make victims doubt themselves. The term comes from a 1938 play by Patrick Hamilton. A perpetrator may gaslight a person into thinking they remember things wrong or misinterpreting things, later making them believe their version of events is true. Routinely belittling a partner and claiming afterwards that it was just a joke or that she was too sensitive is another technique. In some ways, you need to focus not on what the man has done but on what his partner can’t do.

Recognising the red flags is not easy when coercively controlling relationships typically begin in a romantically intense way, with commitment extracted quickly and lots of attention designed to dazzle, as is the case with Ciara and Ryan in Nesting. It’s a form of grooming when women quickly give new partners access to their lives, their homes, families and most intimate secrets.

When that love-bombing phase ends, the victim who loves their partner can perennially hope to return to that sweet spot. Further complicating the matter is that outbursts of controlling behaviour or cruelty can often be interspersed with tender moments, which serve to confuse further.

Even just recognising an abuser for who he is can be difficult because we have an entrenched cultural paradigm of perpetrators of domestic abuse being out-of-control men in contact with the law displaying socially problematic behaviour.

We recognise the shouting, dysfunctional, physically violent stereotypical perpetrator but fail to detect the charismatic abuser, the pillar of society, the man who is highly functioning, middle-class, educated, ‘respectable’ who wears a mask’ and can manipulate his partner but also the outside world which makes him so hard to break free from.

O’Donnell captures this so well in Nesting. To the outside world, her husband appears like a catch.

Ryan is “a nice, well-dressed civil servant. Respectful to everyone. A regular Mass attender. Volunteer at the local GAA club.”

Perpetrators are often narcissistic and highly skilled manipulators who know how to get what they want, which is power and control. They prey on the empathy of their partners taking them hostage.

As awful as it may sound, physical violence is more straightforward. Bruises and broken bones do not lie; they are black and white in a way that coercive control and emotional and psychological abuse are not. Coercive control, in all its complex facets, is never just one single incident but rather a pattern of behaviour that builds up over time and can have a devastating effect.

What is most surprising is who may be most susceptible to coercive control, which hides in plain sight and cuts across every social strata. The bottom line is that any person can become a victim of coercive control. However, smart and professionally successful women may be particularly vulnerable to coercively controlling behaviour, which, on the face of it, seems a curveball.

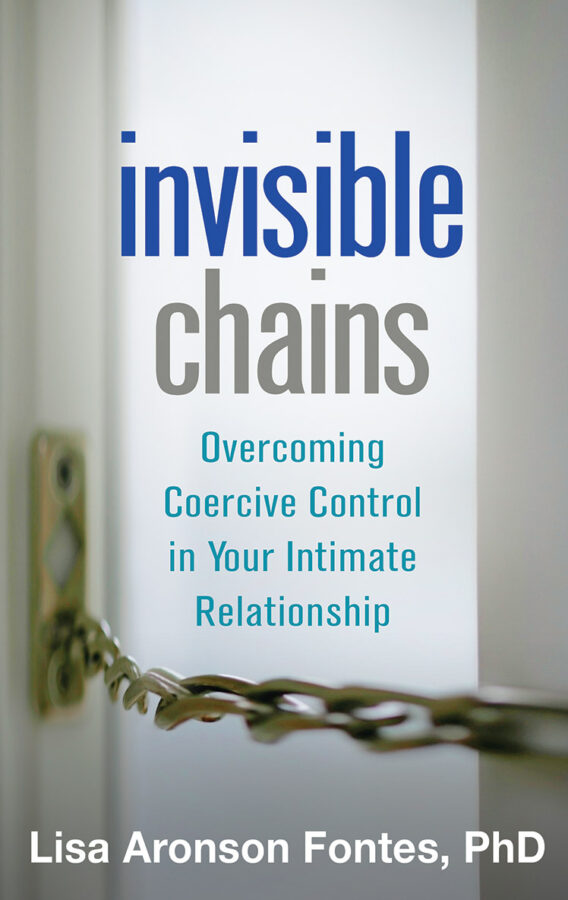

According to psychologist and international expert in domestic abuse, Dr Lisa Aronson Fontes, this is because they are used to figuring out problems, are unaccustomed to failure, and don’t like to back out of difficult situations.

It makes sense when you think about it. You have surmounted every educational and professional challenge in your life. You think you can make the relationship work; you are not a quitter. Meanwhile, in an unhealthy, abusive relationship, your sense of self gets eroded, you lose your bearings, and incrementally, his voice becomes the voice in your head.

“He has spun her around so that the earth no longer feels stable. She doesn’t know which way is forward and which is back”.

In her book Invisible Chains, Dr Fontes admits that she was the victim of coercive control, which seems incredible given her professional expertise until you realise the subtlety and insidious gradualism of coercively controlling behaviour.

Her long marriage had ended, and she met a man who seemed to offer her an ideal, highly romantic relationship which she craved. The control happened gradually, and at first, it seemed flattering. He went everywhere with her; he messaged her continuously until she began to feel smothered. It was only later that she was able to connect the dots. As Aronson Fontes explains, seemingly small restrictions in a relationship add up and lead to the ‘invisible chains’ that make domestic abuse a virtual prison for the victims caught up in it.

According to Fontes, another reason that women can be susceptible to coercive control is that we are culturally conditioned to be caretakers and want to make our relationships work at all costs.

Many experts, including Fontes, consider coercive control to be part of a broader societal problem that raises questions about how women are socialised and about the entitlement of men who see their partners and children as possessions that they can control if they wish.

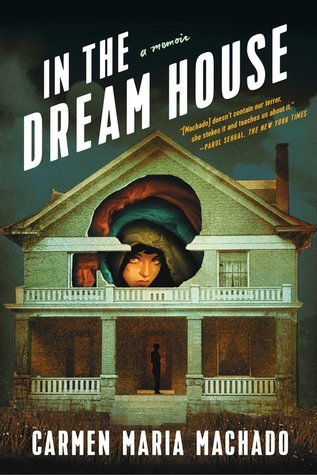

Yet, although most coercive control relationships involve a man dominating a woman, it can work the other way, too, and can happen in LGBTQ relationships. For a take on coercive control in a lesbian relationship, look no further than Carmen Maria Machado’s memoir In The Dream House. This gifted writer powerfully conveys doubting her perception of reality as she suffered abuse from her ‘petite, blond Harvard graduate’ girlfriend bookended with sweetness. She writes, “Your brain is scrambling for an explanation.”

The statistics for domestic abuse in this country are staggeringly high, with An Garda Siochana receiving a call every ten minutes. Decoupling the coercive control cases from those stats is impossible because we lack accurate data. In reality, though, thousands of victims and perpetrators of coercive control remain hidden. They are in every parish, village, town and suburb. They may be your friend, family member, colleague, neighbour, or somebody in your book club or at the school gates.

Coercive control is complicated and challenging to deal with. It’s a hard pill to swallow that the person you may love is your abuser. Shame, societal stigma and pain are just some of the many barriers to leaving. We have inched our way from being a socially conservative country to a liberal one, yet despite television and radio ads urging victims of domestic abuse to seek help, the notion that domestic abuse must be kept in the realm of the family is difficult to overcome.

If you suspect somebody in your life is a victim of coercive control, the advice is to stay connected with them nonjudgmentally, lessen their isolation, opening space for them to confide in you.

Carmen Maria Machado said of her memoir, “I hope that people who need it read it.” If you want to read more about coercive control, you can access any of the 75 books on domestic abuse and coercive control from your local library that Haven Horizons, an organisation dedicated to the prevention of domestic abuse, dedicates annually to Libraries Ireland.

Dr Fontes’ book, which contains checklists to determine whether you or a loved one may be experiencing coercive control, is among them, as is Machado’s memoir. We will be adding O’Donnell’s Nesting to our donation.

And remember, you are not alone, there is always hope.

READ MORE: Nicola Hanney Recounts The Abuse By Her Garda Husband