The Gloss editors select some of their favourite poems on this World Poetry Day – a UNESCO initiative that dates back to 1999 and aims to promote reading, writing and publishing poetry of all genres and in all languages …

Sarah McDonnell, editor

My grandfather used to recite this Hilaire Belloc poem/verse for me when I was a little girl. We were competitive rhymers and wrote verses for each other all the time – ridiculous, zany stuff but we thought they were hilarious and fell around laughing like drains at our exchanges before we headed to the sweet shop for a couple of celebratory liquorice pipes. Belloc was famous for his Cautionary Verses wherein all sorts of ghastly fates befell children and adults who didn’t play by the rules.

That Sarah “did not care a pinch of snuff for literary stuff” was extra-funny as I was a big reader. I also have a sister called Jane (in the poem, Jane is very well-read.) If Hilaire Belloc hasn’t been cancelled he might be soon as it’s all a bit old-fashioned but let’s pray that doesn’t happen – he’s a brilliant forgotten poet for kids. I also read a few Belloc poems to my mother while she was in hospital, fresh from an operation – I think she was still a bit high from the anaesthetic but she was begging me to stop as she was laughing so much. It certainly cheered her up. I think this is clever and charming and has just the right level of violence a child can relish.

A few years ago my lovely aunt gave me her childhood copy with binding falling apart: I treasure it and think of my grandfather reading it to her. I love “proper” poetry of all sorts, from drippy Baudelaire to scaremongering old Milton to Heaney, my GOAT, for sure. A poem can fix you faster than a glass of wine, a walk. A funny one, even faster again.

Sarah Byng, Who Could Not Read and Was Tossed into a Thorny Hedge by a Bull

Hilaire Belloc

Some years ago you heard me sing

My doubts on Alexander Byng.

His sister Sarah now inspires

My jaded Muse, my failing fires.

Of Sarah Byng the tale is told

How when the child was twelve years old

She could not read or write a line.

Her sister Jane, though barely nine,

Could spout the Catechism through

And parts of Matthew Arnold too,

While little Bill who came between

Was quite unnaturally keen

On ‘Athalie’, by Jean Racine.

But not so Sarah! Not so Sal!

She was a most uncultured girl

Who didn’t care a pinch of snuff

For any literary stuff

And gave the classics all a miss.

Observe the consequence of this!

As she was walking home one day,

Upon the fields across her way

A gate, securely padlocked, stood,

And by its side a piece of wood

On which was painted plain and full,

BEWARE THE VERY FURIOUS BULL

Alas! The young illiterate

Went blindly forward to her fate,

And ignorantly climbed the gate!

Now happily the Bull that day

Was rather in the mood for play

Than goring people through and through

As Bulls so very often do;

He tossed her lightly with his horns

Into a prickly hedge of thorns,

And stood by laughing while she strode

And pushed and struggled to the road.

The lesson was not lost upon

The child, who since has always gone

A long way round to keep away

From signs, whatever they may say,

And leaves a padlocked gate alone.

Moreover she has wisely grown

Confirmed in her instinctive guess

That literature breeds distress.

Sarah Halliwell, beauty editor

I’m not a big poetry reader, but forever have a soft spot for Eliot’s The Love Song by Alfred J Prufrock, as a friend gave me a copy when we were 17, which I still have. As teens we perfectly understood its bleak, elegiac mood, and lived then, as now, by its line, “I have measured out my life with coffee spoons”. And more recently I got to know Heaney’s Postscript, which will always remind me of swimming at Flaggy Shore with a bunch of brilliant women from the Burren Perfumery, who take to the water there all year – the magical camaraderie there truly makes it worth making the time to drive out west.

Postscript

Seamus Heaney

And some time make the time to drive out west

Into County Clare, along the Flaggy Shore,

In September or October, when the wind

And the light are working off each other

So that the ocean on one side is wild

With foam and glitter, and inland among stones

The surface of a slate-grey lake is lit

By the earthed lightning of a flock of swans,

Their feathers roughed and ruffling, white on white,

Their fully grown headstrong-looking heads

Tucked or cresting or busy underwater.

Useless to think you’ll park and capture it

More thoroughly. You are neither here nor there,

A hurry through which known and strange things pass

As big soft buffetings come at the car sideways

And catch the heart off guard and blow it open.

Penny McCormick, deputy editor

Faster than fairies, faster than witches,

Bridges and houses, hedges and ditches;

And charging along like troops in a battle,

All through the meadows the horses and cattle:

All of the sights of the hill and the plain

Fly as thick as driving rain;

And ever again, in the wink of an eye,

Painted stations whistle by.

Here is a child who clambers and scrambles,

All by himself and gathering brambles;

Here is a tramp who stands and gazes;

And there is the green for stringing the daisies!

Here is a cart run away in the road

Lumping along with man and load;

And here is a mill and there is a river:

Each a glimpse and gone for ever!

Anytime I’m travelling by train, especially on the Enterprise between Belfast and Dublin, I recall these lines from Robert Louis Stevenson’s classic poem From a Railway Carriage (written in 1885), one of many I learned by heart when I was younger.

I’ve always loved poetry – and tried to enthuse the truculent teens I taught in my former life as an English teacher. Believe me, there’s nothing worse than having to face a bottom set class with some Gerard Manley Hopkins or RS Thomas from Choice of Poets anthology (my own school copy is heavily annotated and much loved).

My strategy was always to start with some fun contemporary poets such as Roger McGough, Adrian Henri and Wendy Cope, before attempting anything pre-20th century. For younger classes, re-enacting Alfred Tennyson’s The Lady of Shalott, Henry Wadsworth Longfellow’s The Song of Hiawatha or Alfred Noyes’ The Highwayman brings back many happy memories and worked a treat. All these childhood poems are dramatic, tragic and romantic. Just the sort of poetry I savour to this day replicated in adult voices from Emily Dickenson and Thomas Hardy to Pablo Neruda and many more …

Some poetry news:

Celebrate: Poetry Day Ireland is on Thursday, April 27. Now in its ninth year, this island-wide celebration invites the nation to read, write and share a poem on the day. This year’s curator is poet Martina Evans, pictured. She has chosen “Message in a Bottle” as the theme for Poetry Day Ireland 2023, reminding us, in the words of Paul Celan, that “a poem can be a message in a bottle, sent out in the – not always greatly hopeful – belief that somewhere and sometime it could wash up on land, on heartland perhaps. Poems in this sense too are under way: they are making towards something.” To find out more about the events on Poetry Day visit www.poetryireland.ie.

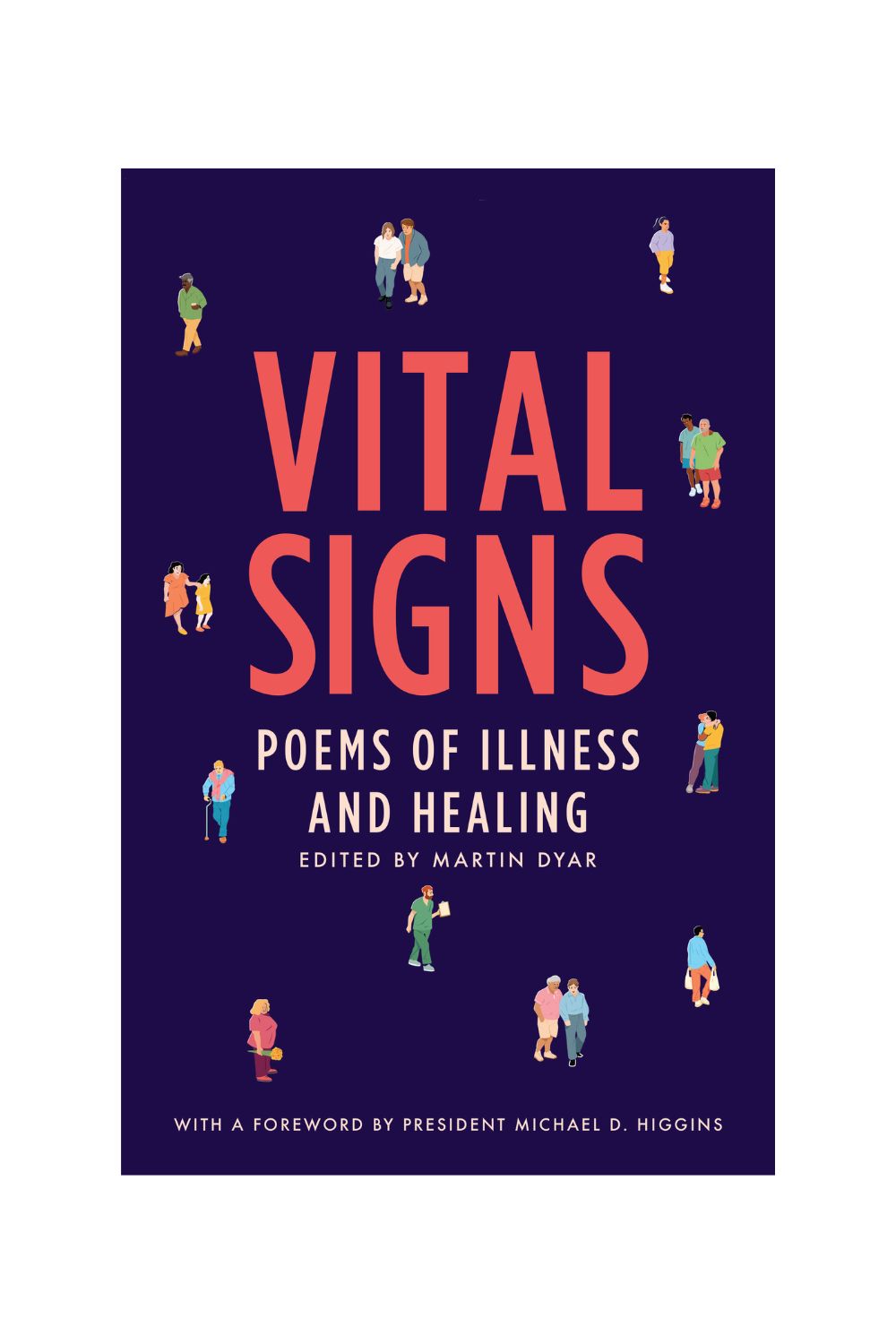

Dip into: Vital Signs: Poems of Illness and Healing, edited by Martin Dyar, which includes poems by Leland Bardwell, Eavan Boland, Christy Brown, Raymond Carver, Imtiaz Dharker, Rita Dove, Vona Groarke, Seamus Heaney, Miroslav Holub, Nithy Kasa, Patrick Kavanagh, Paula Meehan, Paul Muldoon, Colm Tóibín, and many more. Dyar explains, “As much as it discovers what poets have written in response to the human experience of illness and healing, more broadly Vital Signs is also intended more straightforwardly to be a book of poems. As such it can be read solely for the power and the interest of the writing. And that is one basic sense of its title: Vitality in words.”

Read: Poetry Ireland Review Issue 138: An Eavan Boland Special Issue, Edited by Nessa O’Mahony, this issue features personal tributes and reflections along with informative essays focusing on collections and individual poems from Boland’s oeuvre. Featured essayists include Eiléan Ní Chuilleanáin, Thomas McCarthy, Mary Robinson, Colm Tóibín, Martin Evans, and Jody Allen Randolph.