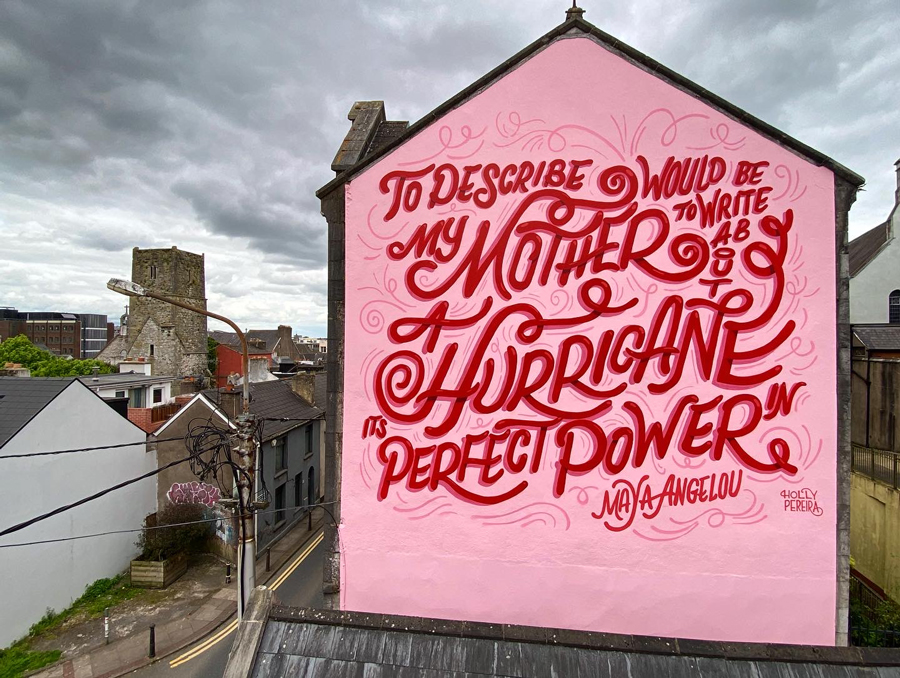

The Singaporean-Irish illustrator and muralist’s bright, beautiful work is instantly recognisable. She describes her love of folk art, botanical motifs and the Irish landscape …

Who or what kickstarted your interest in art?

I’ve been drawing for as long as I can remember. One of my favourite books was Cars and Trucks and Things That Go by Richard Scarry. I was fascinated by the depth of imaginative narratives in the book. It demonstrated a way of creating an alternative reality, not based in the real world; a different way of seeing. It showed me early on the power of art as a tool of transformation.

Thankfully, my parents never put pressure on me to follow a more financially stable career path. Their attitude was “do what you want, as long as you can support yourself”. I studied fine art in NCAD in Dublin, and I have had shows and residencies in Dublin, Berlin, London and Singapore.

By the time I was in my thirties, I decided to shift into illustration, so I trained to be a professional illustrator. The learning curve was steep and there was so much to learn as a freelancer, from software and business skills to how to find clients, work with agencies and negotiate fees.

Your work has brightened up public spaces around the world – how did you get into murals?

I came to murals in two ways. A restaurant asked me to illustrate on their walls, so I became hooked immediately by the scale of big drawings. You can stand there and it can take over your whole body in space – it is immersive.

A few months later, my friends and I decided to paint a mural in support of the Repeal of the Eighth Amendment. There was a lot of very graphic, violent imagery from the anti-choice side littering the streets, so we wanted to create a beautiful visual alternative to that. We wanted to immerse the message ‘Our Bodies, Our Lives, Our Choice’ into a “nice” painting of flowers, sort of like an artistic Trojan Horse. We got a lot of encouragement from passersby, while some people shouted “you’re going to hell”. It felt necessary to add to the discourse surrounding the referendum, in an artistic way.

After painting the piece, I was struck by how you can send a message or concept immediately into the world through art. You have no control over how it is received, but isn’t that the beauty of street art? The work is not enclosed in the often-perceived elitist space like a gallery or museum, so it’s open for everyone to enjoy or hate. Believe me, everyone has an opinion when you paint on the street! The audience for the work is the city, which made me grow a thick skin and lose a lot of the preciousness I’d previously had around my work.

How would you define your style?

I am drawn to motifs and imagery from a lot of folk art from around the world, but especially that of Eastern Europe. A lot of European folk art employs symmetry as a design device, which I love. By and large, people are drawn to symmetry. When I paint folk art murals, it’s a technical challenge for me to keep each side of the wall absolutely symmetrical.

The other thing I love about folk art is that, throughout the world, it is often women who paint it. It is not often considered in the fine art canon, but seen on ceramics, through textiles, as decorative pieces. In some ways, I feel connected to the many women who make this kind of work and celebrate it as the sophisticated artform it is.

Other ways to describe my work would be colourful, vibrant and probably a bit maximalist. I like to layer colour, shape and motif, then cut back. It’s a constant process of addition and subtraction. I have to find that tipping point where the work goes from full and lovely and just right, to a bonkers, unholy mess, then back again.

Tell us about your new tapestries

I have always admired textiles and textile work from around the world. It, along with murals, is one of the oldest art forms. People were weaving and drawing on cave walls thousands of years ago, so it feels thrilling to connect with those practices today. I spent a long time getting the design for this tapestry just right. It was important to me not to add more to the fast fashion threadpile, but to create something that will be a lifetime investment piece – something that never goes out of fashion.

I wanted to create something that spoke of my love of the Irish landscape and flora. I also wanted a dark background with floral elements, like a lot of my mural work. I am inspired by Dutch flower paintings from the 17th century, which look like still life studies of flowers, but each motif is imbued with meaning like the transitory nature of life, death and morality.

I love the fact there are so many ways to use the throws – on the wall like a painting, on the sofa or on your body. I couldn’t be happier with how they turned out.

How and where do you work?

I work from home when I’m not out painting, although I wish I had a studio. The ongoing housing crisis has destroyed a lot of studio spaces, in favour of creating hotels for tourists who come for the culture. It is completely short-sighted, but that is the case in Dublin right now.

I always have a reference in mind, whether that’s tone or mood or palette. I also enjoy researching, so I spend quite a lot of time reading about whatever is pertinent to the brief or theme.

I enjoy working outside (when it’s not raining, obviously), and I usually only make a very rough sketch of what I’m going to paint. I like to leave about 50 per cent of the design up to what happens on the day. There are so many factors to consider – footfall, where the light hits, the angle of the streets connecting – that it’s best to leave a lot of flexibility when it comes to the final piece.

Muralists and street artists say, “when it’s done, take a picture and it’s not yours anymore”. The work then belongs to the public. It could be tagged or painted over the next day, eroded by weather or wear-and-tear, or the wall could be knocked down (to build a hotel!). The best part is when people who actually live and work near the mural take ownership over it – it’s a landmark, they use it as a meeting place, something by which to navigate their city. The work itself is transient. It is a snapshot of where you are as an artist on a particular day, in a particular place. It is such an opposing standpoint from a more fine art approach, from the concept of personal ownership, longevity and legacy. It took me a while to be able to let go of the work. Now, I really enjoy the freedom it affords.

Photograph by Ruth Medjber; @ruthlessimagery

What is your next project?

I am generally working on about five different projects at one time. That could be commercial illustration for advertising, murals for businesses or campaigns, my own online shop, speaking or giving workshops at events and festivals, and personal projects. Every day is different, which is why I love my job – I never know what’s coming next.

Need to Know: Holly’s limited edition tapestry throws made of recycled cotton cost €220 including shipping. www.hollypereira.com/shop. Follow Holly on @holly.pereira